You can access this resource in English here!

Por todo o mundo, existem muitas pessoas de bom coração que sonham em fundar seu próprio santuário para animais de fazenda (inclusive nós do The Open Sanctuary Project). A ideia de cuidar daqueles que merecem respeito e um tratamento compassivo, especialmente espécies às quais o mundo nega compaixão, pode despertar um fervor naqueles que amam os animais como poucas outras causas conseguem. Talvez você tenha visitado alguns santuários maravilhosos pelo mundo, sentido a conexão com os habitantes do lugar e pensou seriamente em como oferecer vidas melhores para mais indivíduos. Talvez você tenha pensado no impacto que a história dos abrigados possa ter nos visitantes, espalhando uma mensagem de compaixão por todo o globo. Ou talvez você nunca tenha pisado em um santuário, mas lhe parece que começar um é a próxima etapa acertada para a sua vida.

Mas antes de dar entrada naquele pedaço de terra em que você pensou, antes de assinar os papéis de adoção daquele porquinho vietnamita abandonado, e antes de preencher a papelada para fundar a organização não-governamental dos seus sonhos, é importante pensar seriamente sobre tudo o que está envolvido em fundar um santuário de animais!

Este material não tem o objetivo de desencorajar ninguém de começar um santuário, mas sim de oferecer uma perspectiva real sobre os muitos aspectos da vida em um santuário e os desafios inesperados que podem surgir ao longo do caminho.

O The Open Sanctuary Project tem uma série de diretrizes que acreditamos que definam um santuário de animais. Leia-as aqui!

Primeiro, considere o seu comprometimento

Tempo

Tempo é um dos recursos mais preciosos em nossas vidas, e fundar um santuário de animais significa dedicar uma boa parcela dele para a causa.

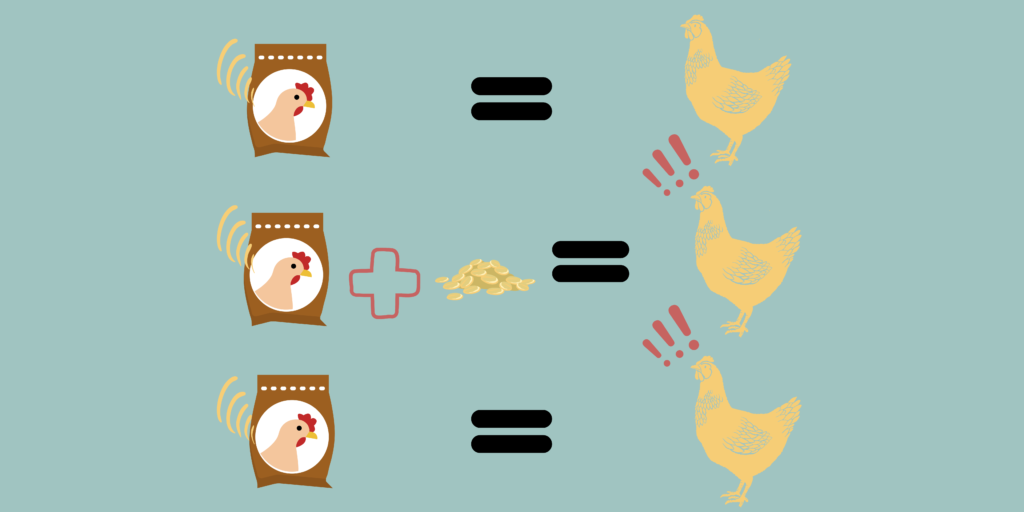

Necessidades diárias: Assim como com qualquer animal de companhia, abrigar um indivíduo em um santuário de animais significa que você está se comprometendo a cuidar diariamente dele, ou seja, alimentando, certificando-se de que a água esteja limpa e a vasilha cheia, atentando-se para que ele não fique doente ou estressado, movimentando os habitantes de e para outros pastos e trocar a forração de seus recintos sempre que necessário. Essas tarefas diárias relativamente simples se acumulam rapidamente conforme aumenta o número de indivíduos que você pretende abrigar. Os afazeres diários e a checagem para ver se os animais estão sendo bem cuidados pode ser um trabalho que leva literalmente o dia todo em alguns santuários, especialmente se não existir um suporte regular de voluntários ou funcionários. E assim que o sol nasce mais uma vez, quase todos esses afazeres precisam ser repetidos, dia após dia, todos os dias do ano!A longo prazo: Quando você acolhe um animal com a intenção de oferecer cuidados compassivos para o resto da vida dele, deve considerar por quanto tempo pretende se comprometer com esse trabalho intensivo. Em termos de animais de fazenda, isso pode significar cuidar de uma galinha por até 10 anos, uma vaca por 20, ou um cavalo por 30! É claro que a maioria dos santuários tem a intenção de abrigar muito mais do que um habitante, o que aumenta ainda mais a demanda de tempo a cada nova vida que é acolhida. Começar um santuário significa firmar um compromisso com todos aqueles que você irá abrigar e que dependerão de você ao longo de todas as suas vidas, inclusive durante uma velhice digna. Até que o fundador deixe a organização que iniciou, essas vidas serão sua responsabilidade.

A longo prazo: Quando você acolhe um animal com a intenção de oferecer cuidados compassivos para o resto da vida dele, deve considerar por quanto tempo pretende se comprometer com esse trabalho intensivo. Em termos de animais de fazenda, isso pode significar cuidar de uma galinha por até 10 anos, uma vaca por 20, ou um cavalo por 30! É claro que a maioria dos santuários tem a intenção de abrigar muito mais do que um habitante, o que aumenta ainda mais a demanda de tempo a cada nova vida que é acolhida. Começar um santuário significa firmar um compromisso com todos aqueles que você irá abrigar e que dependerão de você ao longo de todas as suas vidas, inclusive durante uma velhice digna. Até que o fundador deixe a organização que iniciou, essas vidas serão sua responsabilidade.

Recursos financeiros

Um santuário de animais responsável que cuida de seus habitantes precisa se comprometer a oferecer a melhor vida possível para todos, incluindo alimentação de alta qualidade, suplementos, vacinas, forração, recintos adequados e cuidados veterinários regularmente.

Essa responsabilidade é ainda maior para habitantes resgatados da pecuária intensiva. Pense o quanto dinheiro seria necessário para oferecer uma vida de qualidade para um cão ou gato que tem uma condição crônica de saúde ou que passou por um grande trauma. Para muitas raças industriais de animais de fazenda, o custo para administrar seus problemas de saúde criados pelos humanos pode ser assustador.

Além da responsabilidade com os habitantes, existem muitos outros gastos envolvidos com um santuário de animais que devem ser considerados. Um santuário padrão precisa ter orçamento para:

- Dar entrada na terra e na propriedade

- Estrutura, recintos, construções, cercas, reformas e manutenção

- Equipamentos, veículos e sua manutenção

- Alimentação, forração e suplementação para todos os habitantes

- Energia elétrica, gás e água

- Cuidados veterinários e de saúde

- Funcionários e prestadores de serviço

- Impostos, taxas e suporte legal

E isso é apenas o básico para manter um santuário. Cursos e formação de qualidade, eventos para o público e outras expansões operacionais irão somar ainda mais aos custos mensais. Não é incomum que até os menores santuários tenham gastos que chegam às centenas de milhares de reais ao ano.

Os custos pessoais

Além de todos os cuidados com a manutenção e os habitantes, conforme mencionado, começar um santuário de animais demanda muito tempo e pode ser emocionalmente desgastante para os fundadores. É um compromisso que envolve trabalhar dias e noites por um retorno financeiro mínimo (se não for voluntário) e, ao menos no início, sem férias ou descanso. Cuidar dos habitantes é uma realidade diária não negociável, então, se ninguém pode fazer o trabalho, cabe ao fundador estar no local garantindo que os animais recebam os cuidados necessários. Se você é alguém que precisa de férias frequentemente ou uma pausa para desestressar, começar um santuário pode não ser a melhor opção! Mesmo quando viajam em uma tentativa de descansar, muitos fundadores relatam dificuldades para “fazer uma pausa mental” do santuário. É simplesmente muita coisa para fazer e pensar!

(Alerta de conteúdo para o parágrafo seguinte: menção a danos auto-infligidos ou suicídio. Aqueles que desejam evitar o assunto podem ir direto para “Cuidando dos Humanos” abaixo.)

Trabalhar com os habitantes, especialmente aqueles que têm saúde frágil, pode ser exaustivo, frustrante e deprimente. Pessoas que trabalham com animais lidam com taxas desproporcionalmente altas de luto, depressão, fadiga por compaixão, burnout e, infelizmente, danos auto-infligidos e suicídio. Raramente existe tempo para dar um espaço para si mesmo e processar essas emoções complexas, e várias experiências dolorosas podem se suceder em curtos espaços de tempo. Um fundador em potencial precisa ser resiliente e estar disposto a se afastar e cuidar de si mesmo quando necessário. Ele precisa ter a força para reconhecer que cuidar de si mesmo não é uma fraqueza ou desistência, mas uma necessidade para continuar com o trabalho no longo prazo.

Cuidando dos humanos

Todos os desafios pessoais que o fundador encontra também acometem os funcionários e voluntários de uma forma ou de outra, o que pode causar burnout e uma grande reviravolta no santuário. O fundador precisa cuidar não apenas dos animais e de si mesmo, mas também da organização que oferece suporte e monitora aqueles que trabalham para ela conforme cresce. Muitas vezes, aqueles que são chamados para começar um santuário e cuidar dos animais não têm a experiência necessária para administrar funcionários e lidar com os desafios que isso soma às operações diárias. O fundador precisa estar disposto a olhar criticamente para as suas capacidades e contratar alguém para administrar a equipe de forma eficiente, se necessário. Essa função sozinha já é um trabalho integral!

A visibilidade pública

A não ser que esteja pensando em começar um santuário particular, querendo ou não, você terá que interagir frequentemente com o público, seja para pedir apoio financeiro, para ter ajuda com a divulgação das histórias dos habitantes ou permitir que visitem para conhecer a causa dos animais de fazenda.

Uma dificuldade frequente na administração de um santuário pode ser a opinião do público e as duras críticas de quem não compreende o trabalho árduo e as decisões dolorosas que um santuário tem de enfrentar. Você pode tentar fazer o seu melhor por um habitante, ou para proteger a organização, e ainda sim encontrar resistência ou até perder o apoio da comunidade por conta da falta de conhecimento ou pura antipatia. Como fundador, você precisa se preparar para defender suas escolhas e responder às críticas com sabedoria.

Conforme o perfil público de um santuário vai crescendo, é infelizmente comum que enfrente ameaças de roubo, vandalismo ou até violência por parte daqueles que se opõem à sua missão e mensagem. A reação de algumas pessoas a uma organização se esforçando para salvar animais pode ser assustadora!

A propriedade e localização precisam ser prioridade

Aqueles que estão interessados em começar um santuário precisam se comprometer a fazer uma avaliação longa e detalhada sobre a localização que têm em mente. Embora possa parecer tentador começar um santuário onde você vive, ou em um pedacinho de terra que ficou disponível por um valor tentador, uma aquisição impulsiva sem pesquisar e refletir adequadamente pode levar a sérias complicações mais para frente! O fundador de um santuário precisa definir:

- Onde deve começar o santuário (em termos de clima, área urbana vs rural e se a região já tem muitos outros santuários por perto)

- Se irá alugar ou comprar a propriedade

- Se as restrições de área ou o plano diretor são adequados ao que deseja fazer

- Quais aspectos do local que se tem em vista funcionam bem para um santuário e o que pode se tornar um problema no futuro.

Para saber mais sobre cada um desses itens, confira aqui o nosso material sobre como escolher o melhor lugar para o seu santuário!

Fundar um santuário de animais é fundar uma ONG

Fundar um santuário de animais, independentemente de se formalizar junto ao governo ou não, exige a mesma atenção à legislação e detalhes legais que qualquer ONG ou organização sem fins lucrativos. Antes de começar a agir, você deve pensar em seu santuário como se fosse uma empresa – com a diferença de que santuários não geram lucro! Além de aprender tudo sobre cuidar compassivamente de animais e questões específicas de santuários, o fundador em potencial faz bem em aprender tudo o que puder sobre administração responsável de organizações sem fins lucrativos! Muitos santuários fecharam suas portas por falta de uma administração adequada, o que poderia ter sido evitado com uma pesquisa acerca das dificuldades de organizações sem fins lucrativos, especialmente ONGs.

Captação de recursos

De onde virão os recursos para o seu santuário? A não ser que você possa fundar e manter o santuário por conta própria (o que exige uma análise realista das despesas anuais e gastos inesperados antes de assumir o compromisso), você precisará de diferentes fontes de renda para que, caso uma seja perdida de repente, seus habitantes e a organização não fiquem em risco. Santuários precisam ter uma quantia extra armazenada para emergências a fim de que, caso um dos habitantes adoeça, o restante possa se manter funcionando. Campanhas de arrecadação são complicadas e demandam muito tempo por si só, e muitos santuários se beneficiam com a contratação de um Captador de Recursos para administrar as finanças e conquistar uma estabilidade de longo prazo.

Funcionários

É muito improvável que um santuário se mantenha de forma eficiente por muitos anos, com uma quantidade considerável de animais, sem contratar funcionários. Cuidar diariamente dos habitantes, fazer a manutenção, buscar suporte do público, lidar com voluntários, administrar a organização e calcular a contabilidade exigida por lei são afazeres demais para qualquer fundador realizar diariamente sem comprometer gravemente algum aspecto administrativo ou a qualidade de vida dos animais. Se você acha que só você pode fazer tudo no seu santuário, saiba que essa mentalidade não ajuda seus abrigados! Se o fundador é também o diretor executivo do santuário, precisa administrar uma equipe e cumprir com todas as funções de recursos humanos, além de todos os afazeres do santuário. Má administração da equipe leva a altas taxas de evasão e baixa eficiência.Para saber mais, confira aqui o nosso material introdutório sobre cargos e funções em um santuário de animais!

Legislação

Se você registrar oficialmente o seu santuário (o que traz importantes benefícios para a arrecadação de fundos e parcerias), precisa considerar toda a legislação em vigor que estará envolvida, desde exigências trabalhistas a normas de segurança. Essas questões não podem ser ignoradas por serem muito difíceis ou complicadas, pois podem acarretar multas graves e ameaçar a existência do santuário.

Sucessão e continuidade

Parte da administração responsável de uma ONG envolve ter um plano para quando você deixará a organização. Eventualmente, a missão de uma entidade começa a se perder caso o fundador se recuse a sair pelo bem da causa. Ao criar um santuário de animais, você precisa ter em mente quando planeja sair, como será essa transição e que função gostaria de continuar tendo após deixar a diretoria.

Mesmo que não esteja planejando sair por muitos anos (ou se não está pensando em abrir formalmente uma ONG), ter um plano de sucessão é necessário caso o fundador, de súbito, não possa mais continuar com seu trabalho, seja pelo motivo que for. É irresponsabilidade para com os habitantes não ter um plano B estruturado! Confira aqui o nosso material sobre sucessão!

O cuidado com animais de fazenda apresenta desafios únicos

Embora pareça ser relativamente fácil ao ler informações pecuaristas na internet, oferecer um cuidado compassivo ao longo de toda a vida para animais de fazenda é extremamente complicado e pode ser uma ciência muito imprecisa. Cada espécie tem suas próprias necessidades em relação a exigências de espaço, nutrição, socialização e cuidados de saúde que devem ser consideradas antes do acolhimento. Fundadores de santuários de animais precisam buscar aprender o máximo que puderem sobre o cuidado compassivo das espécies que planejam abrigar, ou ao menos contratar cuidadores que tenham experiência com cuidado compassivo. Muitas práticas da pecuária tradicional são pensadas para beneficiar apenas os humanos, e não os animais, então é importante cruzar as informações com fontes de santuários! É inaceitável assumir um compromisso com animais que você não tem preparo para cuidar.

Encontrando um veterinário

Frequentemente, pode ser desafiador encontrar cuidados veterinários adequados para todos os habitantes sob seus cuidados, já que muitos veterinários de aves ou animais de grande porte não são treinados para oferecer o nível de cuidado que os animais precisam em todas as etapas da vida. Antes de começar um santuário, é importante saber se você terá acesso a atendimento para todas as espécies que planeja acolher. Confira aqui as nossas dicas para encontrar um bom veterinário!

Cuidando dos que não são cuidados

Muitas raças de animais foram alteradas ao longo das gerações para maximizar o lucro humano aos custos da fisiologia e conforto do animal. Galinhas cornish cross, perus brancos de peito largo e porcos criados pela indústria, entre muitas outras raças, encontram diversas dificuldades de saúde e doenças ou complicações que podem ser difíceis de lidar. Ainda mais desafiador é o fato de que muitos veterinários não têm experiência com essas raças, já que a perspectiva da indústria é de que morram cedo, dentro de uma breve parcela de sua expectativa de vida. Se comprometer a cuidar desses animais é se comprometer com tratamentos incertos, inesperados e, muitas vezes, revolucionários, o que gera um custo elevado para o cuidado compassivo ao longo de toda a vida.

Os habitantes são quem são

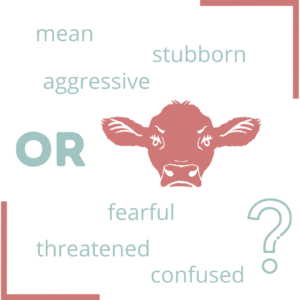

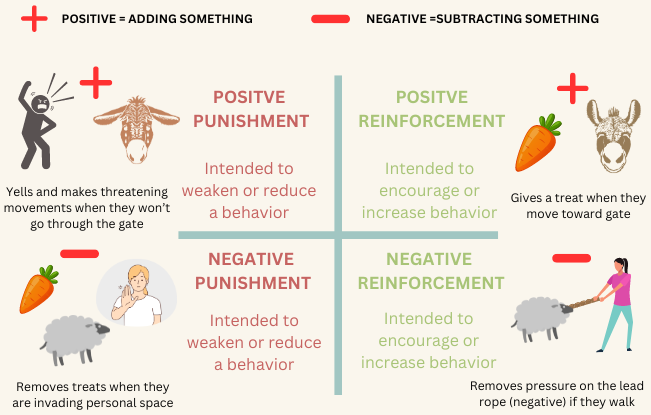

Você precisa considerar que os animais que acolherá são indivíduos, o que traz inúmeras implicações. É difícil prever como será a personalidade de um habitante, especialmente ao assumir animais que sofreram abuso e negligência, mas você precisa se preparar para acolhê-los no estado em que estiverem. Pode ser emocionalmente cansativo cuidar de animais que têm medo ou são agressivos com pessoas, mas é parte do compromisso que você está assumindo ao acolhê-los. Se um habitante não se dá bem com outros (ou nenhum), você precisa encontrar uma forma de deixar todos confortáveis, inclusive separando grupos ou dividindo os pastos, sem negligenciar ninguém no processo. Você não pode assumir que todos ficarão bem e juntos em um único espaço para sempre, e bullying ou abuso frequente entre os habitantes é inaceitável. Você pode ter até habitantes antigos, melhores amigos, que decidem um dia que não suportam um ao outro. Isso precisa ser resolvido para proteger o bem-estar físico e mental dos animais.

Conhecendo seus limites

Um santuário precisa conhecer sua capacidade e não ultrapassá-la. Falhar nisso é um dos principais motivos pelos quais santuários de animais fecham. Se você não quer ter de limitar a quantidade de animais para um número que possa cuidar de forma compassiva com os recursos que tem, deve considerar seriamente se começar um santuário é uma boa opção. Esta é frequentemente a parte mais difícil, mais desgastante emocionalmente, de se administrar um santuário, mas os habitantes dependem de que você tenha em mãos todos os recursos de que precisa para tratá-los! Essa difícil realidade de um santuário pode ser amenizada com a elaboração de uma política de resgates muito antes de começar a receber os animais. Confira aqui como determinar a capacidade de cuidados compassivos!

Prevendo o imprevisível

Se você está começando um santuário, uma das tarefas mais difíceis é ter planos de contingência muito antes de algo acontecer. O que você fará se houver um incêndio? Um furacão? Uma enchente? Se seu principal funcionário parar de ir trabalhar? Se você precisar levar seus habitantes para longe da propriedade o mais rápido possível? Uma administração responsável significa que você precisará agir rápido e ter um plano de contingência pronto para proteger os animais e a organização da melhor forma possível em caso de emergências. Confira aqui nosso material sobre como criar planos de contingência eficientes!

Seja realista acerca das consequências

É uma triste verdade que santuários de animais são forçados a fechar as portas todos os anos ao redor do mundo devido à falta de recursos, má administração ou dificuldade em seguir a legislação. Quando um santuário fecha, seus habitantes frequentemente se encontram em situações tão ruins quanto, ou até piores, do que estavam antes da vida no santuário, animais resgatados são devolvidos a situações de abuso ou vendidos em leilões de abate após perder suas casas. Felizmente, alguns santuários conseguem às vezes agir e ajudar esses animais a encontrar novos lares em outros santuários ou microssantuários, mas isso pode criar uma demanda alta para organizações que já estão lidando com recursos escassos e capacidade no limite. Esses habitantes realocados são às vezes separados de suas famílias ou companheiros, o que já é um processo traumático por si só.

Se tem interesse em começar um santuário, você precisa ser realista sobre os impactos reais de fechar e precisa se preparar para fazer o que for necessário para garantir a segurança dos animais para o resto de suas vidas.

Não existe um modelo pronto

Embora existam muitos santuários de animais de fazenda ao redor no mundo, não existe um guia para seguir e administrar seu santuário (embora o The Open Sanctuary Project tenha muitos recursos que podem ajudar!). Devido às complexas variáveis envolvidas em cada santuário (como localização, espécies abrigadas, quantidade de animais, proximidade de outros santuários, legislação local, possibilidades para a captação de recursos, e outros), é impossível olhar para um santuário único e replicar todas as suas práticas e diretrizes, embora estudar e ser voluntário em muitos santuários pode fazer a diferença na hora de pensar o que pode ajudar a sua organização! Por fim, aqueles que desejam começar seus próprios santuários de animais devem ter forças para tomar uma série de decisões difíceis no que diz respeito à administração da organização e ao cuidado com os animais, muitas das quais não têm uma resposta fácil.

Alternativas para não precisar começar um santuário imediatamente

Em vez de mergulhar no mundo da administração de um santuário e de todas as responsabilidades de ser o fundador, você pode se envolver com a comunidade de santuários para aprender mais sobre como estabelecer o tipo de organização que deseja ter no futuro, ou mesmo em vez de ter um santuário próprio:

Seja voluntário ou trabalhe para um santuário que já existe

Existem muitos santuários de animais ao redor do mundo, e provavelmente algum não muito longe de você! Recomendamos fortemente que qualquer interessado em começar um santuário tenha experiência com vários santuários, seja como voluntário, estagiário ou funcionário, por pelo menos um ano, se não mais. A experiência pode ajudar você a entender a realidade do trabalho e os desafios que surgem todas as semanas em um santuário, além de oferecer uma valiosa perspectiva de dentro acerca das diretrizes e decisões a serem consideradas caso você opte por seguir com a criação do seu próprio santuário. Muitas vezes a rotina diária de um santuário e os desafios que eles enfrentam não são conhecidos pelo público, então simplesmente visitar um santuário ou dois não passa uma imagem completa do trabalho rigoroso que precisa ser realizado dia após dia. Quando se voluntariar, você deve tentar adquirir experiência no máximo de departamentos possível e conversar a fundo com aqueles que estão comprometidos de verdade com esse estilo de vida, questionando sobre as partes boas e também as mais difíceis de sua jornada.

Talvez você descubra que ajudar um santuário existente, seja como voluntário, funcionário de meio-período ou diretor, possa ser satisfatório o suficiente sem precisar começar um santuário próprio. Muitas organizações ficariam agradecidas em ter alguém dedicado e compassivo na equipe!

Considere começar um microssantuário

Em vez de fundar um santuário que tem muitos habitantes, considere abrigar uma quantidade menor de animais no formato de um microssantuário! Microssantuários são uma forma valiosa de acolher animais necessitados com consideravelmente menos recursos do que um santuário grande. Além disso, microssantuários podem ser um exemplo para a comunidade de como cuidar de animais em áreas que não têm santuários maiores. Uma galinha vivendo feliz no seu bairro pode tocar muito mais corações do que uma que está a quilômetros de distância!

Ainda tem interesse em começar um santuário?

Se você considerou com carinho todos esses desafios e questões e ainda tem interesse em começar seu próprio santuário para animais de fazenda, estamos aqui para ajudar! Começar um santuário pode ser desafiador, cheio de dias difíceis, perguntas sem boas respostas, e muitas dificuldades inesperadas que nem nós podemos prever, mas para a pessoa certa pode ser uma missão de vida incrivelmente recompensadora!

Esperamos que você continue por aqui, utilize nossos materiais e recursos e tire todas as dúvidas que tiver! Para começar, confira aqui nosso guia introdutório de primeiros passos.