Resource Acknowledgment

The following resource was written for The Open Sanctuary Project by guest contributor Josué Cabrera. Josué specializes in providing conflict support using the principles of transformative justice. He has worked with multiple organizations and activists within the animal liberationA social movement dedicated to the freeing of nonhuman animals from exploitation and harm caused by humans. movement and is passionate about building communities of care and accountability using a transformative justice framework.

This Resource Is Part Of A Series!

This resource is the first in a series addressing conflict support using transformative justice principles. For Part II of this series, Building Transformative Relationships: Tools for Challenging Dominant Culture in Everyday Interactions, click here!

Introduction

Conflict is an ever-present aspect of our world. Even when we work to model ideals of community, as those involved in farmed animal sanctuaryAn animal sanctuary that primarily cares for rescued animals that were farmed by humans. work do, we still encounter conflict. Because most of us have been conditioned to fear conflict as a precursor to punishment, it can be challenging to envision how conflict can be seen as an opportunity for greater mutual understanding and growth. Ironically, this is particularly true when our work is grounded in an aim to achieve collective liberationCollective liberation recognizes that all systems of oppression are intertwined and acknowledges that working in solidarity with one another to undo all of these oppressive systems is the only way we can achieve a world where everyone, human and nonhuman, is truly free from exploitation and harm.. Instead of coping with conflict and addressing its root causes; we may avoid it or pretend it does not exist. Why is this?

When doing social transformation work, we often center our attention on what can change around us and how we can create better environments. For example, in the farmed animalA species or specific breed of animal that is raised by humans for the use of their bodies or what comes from their bodies. sanctuary and rescue movement, we tend to focus on the harms caused by animal agricultureThe human production and use of animals in order to produce animal products, typically for profit. or other exploitative activities. However, when we focus exclusively on external activities or factors, we risk forgetting that we are also part of that environment that needs to change. Humans are complex and full of contradictions; our activist identities don’t prevent us from replicating norms and behaviors that we have been conditioned to accept as “the way the world works.” In this resource, we will refer to those norms and behaviors as the “dominant culture.” However, our mistakes and actions that have harmed others do not define who we are, but they give us clues about what internal work we need to do. This resource is meant as a tool to help us identify and face the oppressor that lives within each of us so that we can avoid replicating the very harms we wish to mitigate.

Recognizing Dominant Culture

Examples and Scenarios Described Really Are Hypothetical!

All hypothetical examples and scenarios offered in this resource are indeed hypothetical: they are not based on any “real-life situation.” Instead, they are crafted based on some of the many examples of conflicts that may arise in a sanctuary or rescue setting. They are meant for educational purposes only.

Cultural change requires time, patience, and intention. Recognizing how our society has shaped us is useful and necessary to dismantle the systems that oppress us. In order to create those radical transformations, we must allow ourselves to experiment and embody relationships based on care for one another. That’s the work that changes our world and, in turn, the larger world around us. Unless we actively create alternatives, even in the most minor and seemingly insignificant situations, we will continue to fall back on old ways. The dominant culture is highly resilient and capable of evolving. It is what made it so difficult for some of us to take that first step in the work that we do now. It is what fuels the “grind” mentality that has us burnt out and competing for funding, media attention, and movement recognition. It is what creates movement leaders perceived as heroes and puts them on pedestals. It is what prevents us from building the world we deserve.

So how can we start to recognize manifestations of the dominant culture around us? In our organizing spaces, a few characteristics of the dominant culture might look like this:

- Exceptionalism, Power & Control. Decision-making power is concentrated in a small group of people perceived as authority figures who are seen as knowing “best.” When a conflict arises, they get to decide how to handle it and protect their own emotional comfort.

- Example 1: Consider a situation where a sanctuary has one large donor who has funded many of its activities, a community leader who has business interests in a local feed store. The sanctuary is interested in starting a campaign to stop the sale of baby chicks in its community and the funder objects! This is an example of where power (in the form of funding) can lead to conflict.

- External Validation: Quantification & Measurement. A sense of urgency and scarcity drives the prioritization of quantifiable goals that can be delivered to big donors and shared on social media. Internal cultural work, which is often slow and introspective, is dismissed unless it provides quick solutions without altering the status quo.

- Example 2: Imagine a sanctuary that feels compelled to conduct constant rescue activity to drive social media “likes” and donations, even though these activities may create real concerns about capacity. Caregivers within the organization are stressed because while they understand the need for ongoing fundraising, they also feel overburdened and worried about care standards falling. This is an example of how dominant culture can drive work in a way that addresses an immediate need but which might actually undermine the long-term goals of the sanctuary, causing conflict.

- Binary Thinking: Right Versus Wrong. Oversimplifying human relationships and labeling people as good or bad. There is a tendency to establish a “right” and “wrong” way of doing things, to act defensively against the perception of being wrong, and to punish people who engage in open conflict.

- Example 3: Consider an animal activist group working on the question of slaughterhouses. This group decides to issue blanket condemnations of slaughterhouse workers without regard to the fact that those workers may also be highly oppressed and marginalized. This strict binary thinking alienates the animal group from labor groups who want to help liberate workers and the workers who would also love to improve their situation! This might cause conflict between groups who want the very same thing!

Reflective Questions to Consider

1. In what potential ways have these particular norms and characteristics of the dominant culture shaped you and your sanctuary community and space(s)?

2. In what potential ways have you seen these particular norms and characteristics of the dominant culture manifest in your own sanctuary community and space(s), either internally (e.g., in yourself, staff, colleagues, board members, etc.) and/or externally (e.g., in funders, other similar organizations and social movements, etc.)? Can you think of any specific examples?

3. Are there any other potentially harmful characteristics of the dominant culture not described above that you can think of that have manifested in your own sanctuary community and space(s)?

Envisioning Alternatives To Dominant Culture

What might some alternatives to these characteristics of the dominant culture look like? Consider the following alternatives to the dynamics above and how employing them might look in terms of mitigating the conflicts listed in the examples above.

- Acknowledge Power (in all its manifestations). Recognize how power differences impact individuals and the group. Provide support for individual freedom and autonomyThe ability for individuals to have access to free movement, appropriate food, and the ability to reasonably avoid situations they wish to avoid. within the group’s purpose.

- Example 1: In our example of the conflict between the sanctuary and its funder, the power dynamics are very apparent. Funding is vital for the sanctuary’s operations, and alienating a significant donor would cause them difficulties. But should the donor’s wishes impact their larger goals, or would a frank conversation about this dynamic benefit both parties in understanding each other better?

- Lead With Purpose, Practice Values. Ensure that our goals reflect not only what we want to achieve but how we want to do the work as a group. We need to create space to experiment, fail, and adjust to our group’s reality.

- Example 2: In our example above of the sanctuary feeling pressed to do constant rescues, what if they instead considered as a group what they want to model in terms of high care standards, and how limiting their capacity could give them the opportunity to model great examples of care to the public?

- Appreciate our Diverse Strengths & Evolve Together. This means creating feedback loops that allow for informed and inclusive decisions, paying attention to nuances, practicing active listening, and approaching mistakes with curiosity as learning opportunities.

- Example 3: In the example of the activist group stigmatizing slaughterhouse workers, what if they considered how to include those workers in their circle of compassion and advocate on their behalf as well?

Reflective Questions to Consider

1. In what ways might you and your sanctuary community members consider applying these alternative practices and values to your sanctuary’s missions, visions, goals, daily practices, and routines?

2. In what particular ways might these alternatives positively impact your sanctuary community and space(s)?

3. Are there any other alternative practices and values not described above that you can think of that might help mitigate harmThe infliction of mental, emotional, and/or physical pain, suffering, or loss. Harm can occur intentionally or unintentionally and directly or indirectly. Someone can intentionally cause direct harm (e.g., punitively cutting a sheep's skin while shearing them) or unintentionally cause direct harm (e.g., your hand slips while shearing a sheep, causing an accidental wound on their skin). Likewise, someone can intentionally cause indirect harm (e.g., selling socks made from a sanctuary resident's wool and encouraging folks who purchase them to buy more products made from the wool of farmed sheep) or unintentionally cause indirect harm (e.g., selling socks made from a sanctuary resident's wool, which inadvertently perpetuates the idea that it is ok to commodify sheep for their wool). in your sanctuary community and space(s)?

4. Are there other alternative practices and values not described above that you can think of that might help build and reinforce more community relationships based on care for one another?

Turning Theory Into Practice

All those alternatives sound good, but the question now is: how do we get there? Knowing the alternatives doesn’t mean we automatically know how to practice them. In fact, that is often the most challenging part of the process. Changing old habits is difficult, even when we know they are harmful. It starts with each of us doing our own internal work, engaging in critical thinking, and recognizing and challenging our own conditioning and biases. It also requires us to intentionally create space for others to do the same, hold ourselves accountable and support others when we fall short, and continuously reflect on our processes and relationships. We can’t expect to dismantle oppressive systems if we replicate those same systems within our own movements.

Let’s be clear, this work is hard and uncomfortable, but it is necessary. It requires vulnerability and willingness to be wrong, learn, and grow. We must be patient and compassionate with ourselves and each other, knowing that we are all imperfect beings on a journey of growth and transformation. By doing this internal work and creating alternative ways of organizing, we can create a more just, equitable, and compassionate world for all.

Download Our WorkbookTo Practice With Your Organization!

We’ve put together a workbook that your group can use as an exercise in thinking about dominant culture, how it may have manifested in your experiences, and how you can envision alternatives. Enter either your organization’s name or your name and email below to download the workbook! We promise not to use your email for any marketing purposes! Need to access this workbook in a different way? Contact us!

Defining “Justice:” Understanding Punitive Justice And Its Alternatives

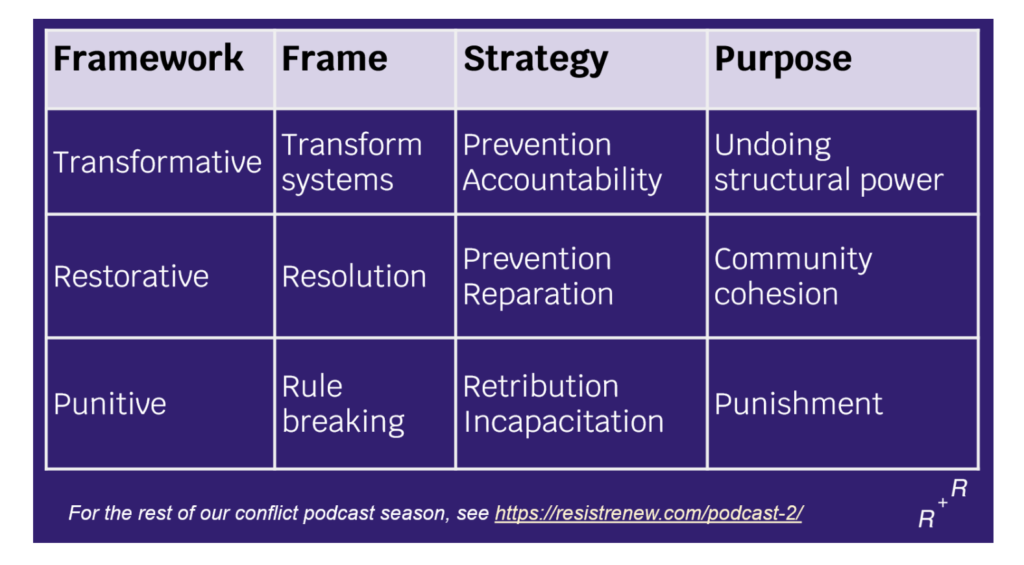

In this series, we’ll discuss three types of justice: punitive, restorative, and transformative. We’ve been conditioned by the dominant culture to view punitive measures as the only or best way to achieve justice, and we’ve been prevented from developing the skills needed to envision and implement alternatives.

In many countries influenced by European approaches to justice, “getting justice” amounts to punishing a person who breaks rules or laws. However, punitive justice does not prioritize the needs of those directly involved in the situation or the broader process. Instead, it reduces problems to a single individual’s behavior without addressing systemic issues. An authority figure determines the process, goals, and outcomes and often only intervenes when rules are broken rather than when harm occurs. To read more about punitive, or legal mechanisms for conflict resolution, you can check our resource here.

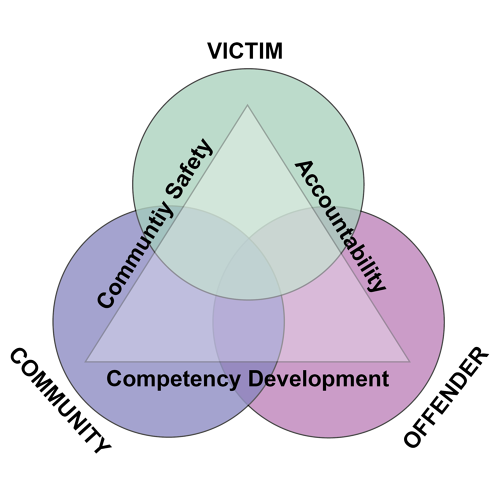

In contrast, restorative justice acknowledges the impact on both the individuals involved and the community. It seeks to hold the person(s) responsible for the harm accountable and provides a form of reparation. It allows for complexity and is less likely to lead to the removal of individuals from their communities.

However, one shortcoming of restorative justice is that it often relies on existing institutions and processes that fall short of creating alternatives and critiquing systems of oppression by solely holding individuals responsible for situations.

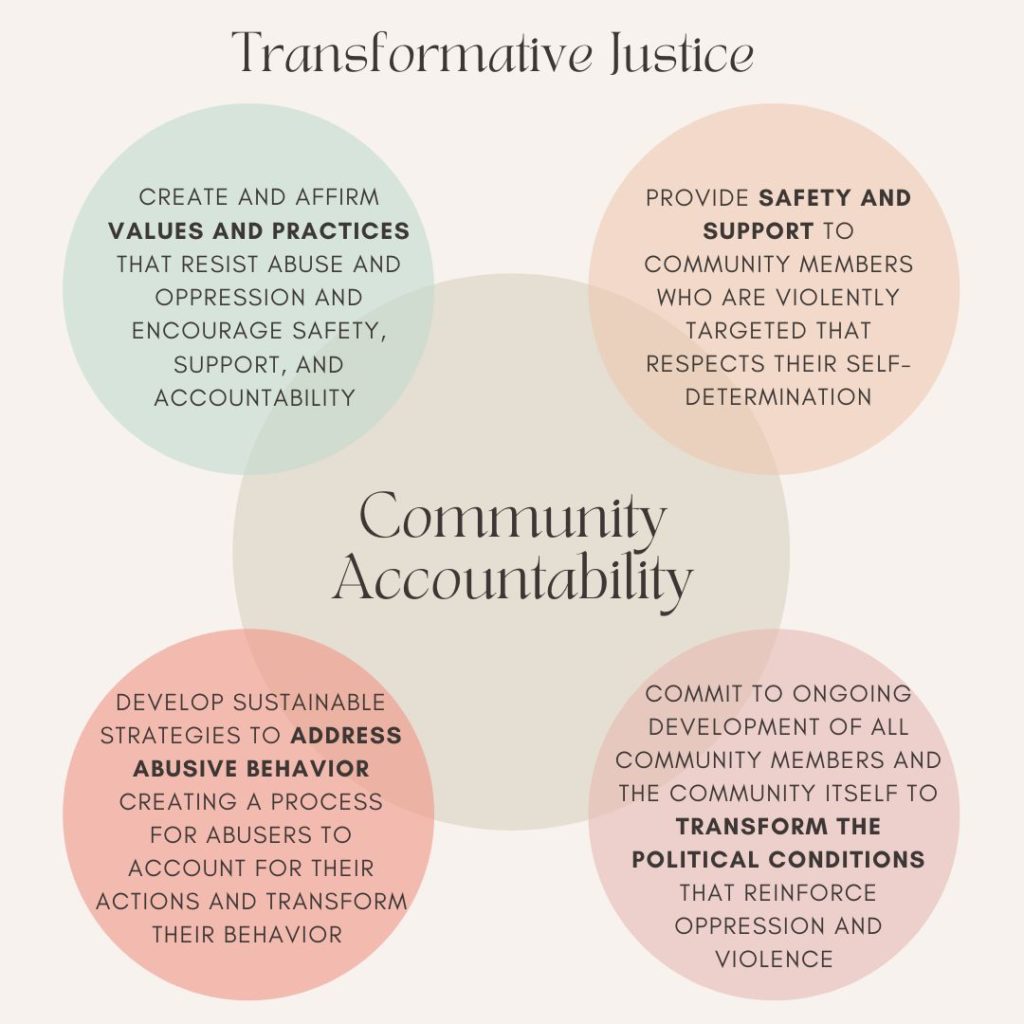

In contrast, transformative justice is a framework grounded in the belief that people occupy multiple roles and can be both harmed and harm others. It seeks to ensure the safety and healing of everyone involved and adapts the process to the specific situation. It encourages the imagination of alternatives beyond the current system to address issues of power and privilege. This approach may seem idealistic, so implementing it on a large scale can pose a significant challenge. Its power lies in relationships rather than third-party objectivity. However, in smaller-scale communities, such as farmed animal sanctuariesAnimal sanctuaries that primarily care for rescued animals that were farmed by humans. and rescue, where we seek to model an alternative way of existence that rejects the assumptions and hierarchies of the dominant culture, transformative justice may be an attainable and attainable and workable ideal!

How Can We Distinguish Punishment From Consequences?

In considering punitive, restorative, and transformative justice, one of the most helpful ways to envision how they may play out in our communities is to consider punishment. In the dominant culture, we are conditioned to see punishment as the go-to solution for conflicts, even when it goes against our values and principles. However, accountability cannot be forced, and people can only make themselves accountable for their own actions. As Shannon Perez-Darby says, “Accountability is a human skill, not something that happens to bad people.” That skill is to be willing to report back to the group, to take ownership of the consequences or outcomes of their action, positive and negative, to learn from mistakes, make amends as needed, and change their behavior in the future. This resource series aims to provide you and your community with tools that can transform the context of harm so self-accountability becomes the easiest solution instead of perpetuating a cycle of violence.

Behavioral norms are defined by the group, and the consequences for breaking them are determined through a collaborative process. It’s crucial for the team to agree on these norms and the corresponding consequences. In situations where harm has occurred, it’s essential to prioritize the needs of those affected and adapt the agreed process to the complexity of the current situation. Consequences aim to halt further harm, ensure safety for all community members, and provide opportunities for reflection, growth, healing, and transformation. In contrast, punishment seeks to harm others, establish dominance, reinforce hierarchies, and maintain the status quo.

To determine whether your practice of conflict resolution relies on punishment, consider the following questions as a group:

- Do you have a clear, short list of norms, values, and accepted behaviors that everyone in your group agrees upon?

- Do you have protocols or a process for handling conflict?

- Do you prioritize resources for everyone in the team to build capacities to navigate, mediate, and support conflict situations, not just the HR department?

- Does the conflict resolution process center the needs of people directly involved and provide support to everyone?

- Are resources allocated to supporting people to engage in an accountability/recovery/healing process if needed?

- Are the consequences creating harm? Note the difference between harm and discomfort.

In principled communities, it is easier to be accountable for one’s actions. Answering the following questions as a group can create a container for alternatives to thrive:

- What is the purpose of your group?

- Who is responsible for getting work done?

- How do you share information within the group?

- How do you make decisions?

- How do you evaluate what is working and what’s not?

Although these questions may seem basic, revisiting them with your whole team and allowing brave conversations to lead you to better answers can create a more accountable and transformative community.

Example: Social Media and Accountability: How to Avoid Punishment Mentality

Social media can be a powerful tool to share information quickly, but it can also be a platform that reinforces a punishment mentality rather than true accountability. When harm occurs in your community, social media commentary about it may spread rapidly. Depending on your role in the situation, you may feel compelled to post statements, apologies, accusations, or updates about the accountability process. Here are some tips that can help you navigate this situation.

Tips For Community Members (Bystanders)

If you are a community member, you may feel the need to make a statement about the situation to protect the organization’s public image, to show empathy and solidarity with the people directly involved, or to update the public about the accountability process. Before posting, ask yourself these questions:

- What are the needs and wants of the person that was harmed? It’s essential to follow the lead of the people directly involved in the accountability process, including the person harmed, the person that caused harm, and the facilitators. If you don’t know their needs and wants, then ask yourself the next question.

- Why do you feel the need to post about it? Slow down and reflect on the impact that your post could have on the process and individuals involved. You might feel pressured to post about the situation in order to promote a certain image of yourself.

- Can I support the accountability process offline? Reach out to the facilitators and offer specific support that you could provide. Accountability processes are complex, emotionally draining, and require all sorts of tools and skills. Chances are your support will be needed and appreciated.

Tips For Accountability Facilitators

Accountability facilitators are community members directly supporting the conflict support process. If you are directly involved in the process, ask yourself these questions before posting:

- Is posting helpful in creating conditions for healing and transformation? Consider the impact that your post could have on the accountability process and the individuals involved.

- How much information is appropriate to share? Share only what is relevant and important for the community to know about the process. Keep in mind that too much information can be overwhelming. Avoid triggering or retraumatizing the person harmed.

- Do you have social media agreements with the people involved? Social media agreements can help establish clear boundaries and expectations around what can and cannot be shared.

- If posting an apology, is that what the person harmed needs/wants? Are you speaking to the person or the community? Are you doing it to be perceived in a certain way?

By following these tips, you can help to create conditions for healing and transformation without relying on punishment as the go-to approach when sharing about a situation of conflict on social media.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is clear that moving away from punitive approaches to behavior and accountability is a complex and ongoing process that requires patience, humility, imagination, and experimentation. It is essential to recognize that group dynamics are constantly evolving, and this work has no one-size-fits-all solution.

Building a solid community where individuals feel safe and supported is critical to cultivating a culture of self-accountability. This means creating a space where people are not afraid of being punished, banished, or labeled as “bad” for making mistakes or breaking agreements.

In future resources in this series, I will be sharing tips and tools for engaging in the process of agreeing on behavior norms, principles and values, and consequences for when agreements are broken. These resources will also focus on strengthening communities, cultivating a culture of mutual aid and solidarity, and improving communication skills.

It is important to remember that we all replicate the dominant culture to a certain degree and face individual and collective trauma from living under capitalism in a colonized world. Therefore, we must avoid blaming, shaming, or harming each other as we navigate this process together. We must prioritize self-care and care for those around us to move forward with intention and compassion. By engaging in this work, we can not only challenge the harmful aspects of the dominant culture but will make our efforts stronger and more sustainable, leading to better outcomes for the animals we care for.

To read more about conflict support for your animal organization, check out Part II of this series, Building Transformative Relationships: Tools for Challenging Dominant Culture in Everyday Interactions. To find that, click here!

SOURCES:

Determining Your Animal Sanctuary’s Capacity For Responsible Care | The Open Sanctuary Project

Fostering Critical Thinking At Your Animal Sanctuary | The Open Sanctuary Project

Transforming Culture | Josué Cabrera

Transformative Versus Punitive Approaches To Conflict | ResistRenew.Com

A Brief History Of Punitive Justice | Psychology Today

About Restorative Justice | University Of Wisconsin-Madison Law School

Transformative Justice: A Brief Description | Transform Harm: A Resource Harm For Ending Violence

What Are Community Accountability & Transformative Justice? | TransformativeJustice.EU

Healing Resistance: A Radically Different Response To Harm | Kazu Haga

When We Fall Apart: A Movement Primer | Dragonfly Partners & Interrupting Criminalization

Turning Towards Each Other: A Conflict Workbook | Weyam Ghadbian, Jovida Ross

Holding Change: The Way Of Emergent Strategy Facilitation And Mediation | Adrienne Maree Brown

Self-Accountability & Movement Building With Shannon Perez-Darby | Project Nia & The NYC TJ Hub