Resource Acknowledgement

The following resource was originally developed for The Open Sanctuary Project as part of Dr. Emily Tronetti’s dissertation project in pursuance of her Doctor of Education (EdD) through Antioch University and the Institute for Humane Education. Emily specializes in adult humane education and applied animal behavior, and is passionate about helping advocates and organizations cultivate compassionate coexistence through teaching about and supporting the agency and wellbeing of other animals. We are so grateful for her collaborative efforts and contributions to The Open Sanctuary Project.

This Resource is Part Four of a Fully-Downloadable Guide!

This resource is the fourth part of a fully-downloadable guide that was originally developed as a comprehensive resource to help sanctuary educators foster and teach about farmed animalA species or specific breed of animal that is raised by humans for the use of their bodies or what comes from their bodies. agency and consent in the context of sanctuary education and outreachAn activity or campaign to share information with the public or a specific group. Typically used in reference to an organization’s efforts to share their mission.. In our efforts to make larger resources like the fully-downloadable guide as accessible as possible in various formats, we broke it down into six individual parts/resources. If you’re interested in reading the fifth part of the original resource, “A Guide to Fostering Farmed Animal Agency in Sanctuary Education: Part Five”, please click here. If you’d like to access the fully-downloadable guide, please click here.

Non-Compassionate Sources

We at The Open Sanctuary Project disavow animal experimentation and any “use” of animals for human purposes. Because compassionate studies on valuing the personality, intelligence, and unique attributes of many nonhuman animals are rare, in this resource, we draw from existing sources that may be non-compassionate. Still, we may use the information we find to improve the lives of residents. We strive towards a future when compassionate, non-exploitative, and non-invasive research is the norm. In the meantime, we will work with what we have to help sanctuaries help animals as effectively as possible. You can read a little bit more about our non-compassionate source policy here.

Reflection Questions

Throughout this resource, you will notice questions in boxes like this. To get the most out of this guide, we encourage you to pause and reflect on each question and discuss them with your colleagues. To help with this, please click here for a list of the reflection questions and space for you to share your thoughts.

How Do We Foster Agency During Sanctuary Education?

In this section, we’ll explore different considerations that can help sanctuary educators recognize and support resident agency during educational encounters, and we’ll also contemplate alternative forms of engagement.

Firstly, it’s important to revisit the question of what sanctuary education looks like in your sanctuary. As we proceed through the following considerations, we invite you to reflect on your sanctuary’s current programs and practices and envision how you might modify these to better prioritize the agency and consent of residents while simultaneously facilitating impactful human experiences.

Environmental Considerations

For onsite programs and events, it’s important to consider the environment and how this may impact the resident experience. Residents must feel safe in the presence of visitors and volunteers, and the way their environments are constructed plays a big role in this. For example, some sanctuaries have noted that their chickens seem more comfortable when they have access to trees and shrubs, which provide cover for chickens and a sense of protection from predators. Chickens may sometimes perceive strange humans as potential threats, so the presence of additional coverage, such as trees, shrubs, and perches, can increase overall feelings of safety and agency. Like chickens, most other farmed animal sanctuaryAn animal sanctuary that primarily cares for rescued animals that were farmed by humans. residents are prey animals, which means they’re particularly sensitive to the possibility of threats. Many animals have zones of proximity where they feel comfortable versus where they don’t (E. Abrell, personal communication, June 13, 2023). Some may also feel safer when they have a clear line of sight, whereas this may be less of a concern for other species and individuals (Abrell, 2021).

Fences can also be extremely important tools for promoting safe, consent-based interactions, especially when children and/or large animals are involved (Abrell, 2021). While there may be concerns that visitors will have less impactful experiences if fences separate them from the residents, the potential benefits of barriers deserve consideration. For example, the residents who want to engage will approach the fence if physically able to, whereas those who don’t want to engage are less likely to (unless there are competing motivators like food, which we’ll talk more about soon). As sanctuary educators, we can remind our guests that the sanctuary is the residents’ home, so it’s important to be respectful of that. Depending on various factors, including the individual residents and their unique circumstances, this might mean keeping guests outside of their living spaceThe indoor or outdoor area where an animal resident lives, eats, and rests..

If you determine it’s safe and appropriate to bring visitors into the residents’ living space, it’s critically important that there’s enough space for each resident to move away and not feel pressured to engage. Residents should not be crowded or cornered by visitors. This is going to look different for each individual animal. Some will require more space to feel comfortable than others. This is why understanding the species, unique body language, communication, and perspective of each resident is key!

One possible approach to promoting resident agency and consent during sanctuary education is for each enclosure to have a clearly designated “safe space” that residents know they can retreat to at any time and won’t be bothered. This could be a certain pasture or paddock within a larger fenced-in area or a part of their barn/shelter. For example, when visitors are in Pearl the sheep’s paddock, and she chooses to go into her barn, this may indicate she’d like some alone time. It can be helpful to point this out to visitors, too.

It’s important to give the residents an opportunity to choose these spaces for themselves. Observe where they choose to retreat if they feel overwhelmed or when they simply want to rest unbothered. This will look different for different species and individuals. Depending on where residents choose to retreat, it may be necessary to reassess where we bring visitors. If a resident doesn’t already have a preferred safe space, they should be provided with a variety of options that they find comfortable, enriching, and easily accessible. It’s important to ensure that a resident’s path and entrance to these spaces is never blocked by any obstacles, including visitors. Over time, residents can come to understand the meaning of these spaces. They’ll begin to associate going into these areas with safety and with humans leaving them alone. This can be reinforced by having enrichment available to aid in decompression and to ensure their safe spaces are also places they enjoy.

Alternatively, or additionally, if visitors are allowed into resident living spaces, you might consider clearly designating a place for visitors to stand or sit, such as benches, that visually signal where they’re expected to be. Folks who are sitting, as opposed to standing and looming over the residents, may also be less stressful for the residents. It’s also an easy way to promote clear communication between species. For example, if the visitors are sitting on the bench in the sheep pasture, this indicates to the sheep that visitors would like to interact. The sheep can then choose whether or not they’d like to approach and interact with the visitors. Some sheep might communicate their consent by approaching the benches and sniffing or nudging a visitor’s hand. Over time, the sheep will learn that a visitor sitting on the benches means they will not be followed, pursued, or touched without their consent. This will help the sheep build trust in humans, and with time, you may even notice the sheep choosing to interact with visitors more frequently because they’ll feel more in control of the interaction. Benches can provide a lot of other benefits as well. They may serve as environmental enrichment for residents like goats, who like to jump up on things, or as places to sit and rest to help make sanctuary visits more accessible for more folks. If benches are placed in shaded areas (like under trees, shade sails, or awnings), they can also provide additional relief and consideration of various health issues for both visitors and residents. As you consider the potential benefits of benches and other seated designated visitor spaces inside resident living spaces, however, please be mindful of human safety at all times. Depending on the resident, getting lower to the ground can also put humans at risk of being mounted or bumped in the chest or face.

It’s also important to assess how the mere presence of visitors or other environmental changes that occur during events may impact the agency and well-being of residents. For example, if hosting a live band during a fundraising event, how does the music affect the residents? Is the volume at a level that they can escape by entering their shelters or going out into their pastures? What about traffic and other sounds that crowds make? The time of day you facilitate your programs, as well as the weather, temperature, humidity, and presence of insects, are other environmental factors to consider that can impact the residents’ agency and well-being.

As you begin to consider the various environmental factors that can impact the agency and well-being of the residents at your sanctuary, it can be very beneficial to ask the caregiving staff for input from their perspective as well. As staff who work directly with the residents on a daily basis, they’ll be able to offer unique insight into how a particular educational event, program, activity, or practice might potentially affect the residents. Sanctuary educators should collaborate with caregivers regularly to ensure they’re supporting the well-being and agency of the residents throughout the entire duration of their programming.

Reflection Questions

How has the animal care team at your sanctuary been involved with the development of onsite education programs? In what ways can they contribute to this development? What insight might they be able to offer, particularly with regard to the many environmental considerations you’ll want to make as a sanctuary educator?

Resident Considerations

As mentioned earlier, recent research investigating visitor experiences at a sanctuary discovered that the most memorable and impactful moments were those spent directly interacting with the residents (Beggs & Anderson, 2020). With this in mind, however, it’s critically important that we don’t sacrifice the agency and well-being of the residents in favor of what we assume are better visitor experiences. It’s possible that prioritizing resident well-being may actually help us promote perspectives on farmed animalsA species or specific breed of animal that is raised by humans for the use of their bodies or what comes from their bodies. that are more aligned with the world we hope to play a role in creating. But how do we go about doing this? What considerations do we need to make with regard to our onsite education programs to ensure we’re prioritizing resident well-being and facilitating an impactful experience for visitors?

Reflection Questions

Take some time to reflect on your sanctuary’s current onsite educational programming (if applicable). What are some ways that these programs might impact resident agency and well-being?

It’s imperative that sanctuary educators deepen their knowledge and understanding of species-specific and resident-specific behaviors and emotions with special consideration given to the ways in which each individual conveys consent and other needs. Having a better understanding of each individual resident allows educators to make more informed decisions during their educational programming, such as when it’s truly mutually beneficial for visitors to interact directly with the residents, how much time to spend with residents, how much space the residents need, etc. For example, you may discover that most of the cowsWhile "cows" can be defined to refer exclusively to female cattle, at The Open Sanctuary Project we refer to domesticated cattle of all ages and sexes as "cows." are less interested in visitors, while most of the goats get excited about them. In this scenario, it might be better for visitors to stay outside of the cows’ living space while observing them. However, visitors could potentially be allowed into a designated area in the goats’ living space for a more direct experience during their time at the sanctuary.

“If behavior is a window into how an animal is feeling, then the capacity … to assess how animals are faring will depend on careful observation. Much can be gained, in terms of animal well-being, if a human knows the animals and is closely interacting with them and observing their behavior.… For example, the ears, nose, and eyes of a cowWhile "cow" can be defined to refer exclusively to female cattle, at The Open Sanctuary Project we refer to domesticated cattle of all ages and sexes as "cows." are an excellent window into how she is feeling. Research by Helen Proctor and Gemma Carder found ear movements can be a reliable, noninvasive measure of an individual’s emotional state. The cow’s ears project backwards in a more relaxed position after they are stroked, which the researchers took to be a positive and low-arousal emotional state. Another study found that the white of the eye can be an indicator of emotion in [cows]. When cows are scared and frustrated, we see more eye white than when they are stroked and calm. We also know that a cow’s nose can tell us about their emotional state. There is a decrease in nasal temperature as their stress level falls. To pick up on these behavioral cues, however, the human caretakers have to know their animals and be paying attention.”

Bekoff & Pierce, 2017, p. 45

One way to ensure sanctuary educators have a deeper understanding of the residents is to maintain a file for each resident that can be easily accessible by all staff and volunteers. The file should be a living document that’s updated regularly, and it could answer questions about each resident, such as the following:

- What’s their story?

- What’s their behavior like in various circumstances and contexts?

- How do they communicate various emotions?

- What are their likes and dislikes?

It’s important to get as specific as possible and necessary given your sanctuary’s goals. For example, a sanctuary with an on-site visitor program will likely prioritize different information than a sanctuary that doesn’t have a visitor program. When describing likes and dislikes, a sanctuary with a visitor program might want to include whether or not each resident typically enjoys interacting with unfamiliar people. They might also want to describe what successful interactions have looked like to set future interactions up for success.

Sanctuary educators should study these files, but we should also take ample time to observe the residents and get to know them personally. Our relationships and interactions with the residents are likely different than the relationships they have with others. We should make note of these differences.

Other resident-specific factors to consider when inviting visitors into their homes include:

- Space (see environmental considerations)

- Number of residents, the social dynamics between them, and how this is impacted by the presence of visitors

- Number and duration of interactions with humans

- How many interactions does one animal have in a given visit? How many visits per day? Per week? How often should humans interact with the residents?

- Should interactions be direct or indirect? For the purpose of this resource, direct contact is interacting with the residents without the presence of a barrier, such as a fence, while indirect interaction is through some type of barrier. Which types of interactions are safest for the humans and the residents involved?

- How much time are residents given to decompress between interactions/visits?

- Current routine, behavior and agency

- For example, if a pig is napping when you arrive with visitors, should they be disturbed? How do we know if they consent or not when they’re sleeping?

- How disabilities, health, and age may impact resident behavior and agency

- For example, a chicken with mobility issues may not be able to move away from visitors as quickly as her friends or move away at all. If we’re aware of this, we can instruct visitors to give her more space or not to approach her.

Reflection Questions

If a resident has either temporary or permanent disabilities, how might this impact the ways in which they express consent or non-consent? What kinds of specific accommodations can sanctuary educators make to ensure they are prioritizing the unique needs of disabled residents?

Sanctuaries are often caring for several individuals of various species, each with unique histories, some with trauma, some who were not socialized, and some with other factors that influence their behavior. This can result in some complex behavior concerns that many sanctuary staff and volunteers simply don’t have the knowledge to address in a way that supports agency, safety and long-term well-being. So, enlisting the help of experts, such as animal behaviorists or consultants who utilize compassionate agency-centered practices, is another strategy for sanctuaries to consider.

Identifying and Responding to Resident Consent

As sanctuary educators, it’s our responsibility to reflect on the various factors that can impact whether or not a resident consents to an interaction. It’s also our responsibility to know how to identify and respond to the consent and non-consent of residents at any given moment and know how to guide our visitors in doing so, too.

Considering the consent or non-consent of other species allows them “to have a voice in representing [their] own needs” (Fennell, 2022, p. 4). With some animals, in some circumstances, it’s quite clear what they’re trying to communicate. But oftentimes, it can either be unclear, or our own biases and assumptions about other animals may muddy our interpretations. This highlights the importance of deepening our understanding of resident behavior and communication in order to better understand their needs and preferences. Without adequate understanding, there’s a risk of misinterpreting their signals or missing them altogether and potentially causing harmThe infliction of mental, emotional, and/or physical pain, suffering, or loss. Harm can occur intentionally or unintentionally and directly or indirectly. Someone can intentionally cause direct harm (e.g., punitively cutting a sheep's skin while shearing them) or unintentionally cause direct harm (e.g., your hand slips while shearing a sheep, causing an accidental wound on their skin). Likewise, someone can intentionally cause indirect harm (e.g., selling socks made from a sanctuary resident's wool and encouraging folks who purchase them to buy more products made from the wool of farmed sheep) or unintentionally cause indirect harm (e.g., selling socks made from a sanctuary resident's wool, which inadvertently perpetuates the idea that it is ok to commodify sheep for their wool).. When it comes to consent-informed interaction with other species, it’s crucial to approach these interactions mindfully, even before the interaction occurs. We must acknowledge the power we have in getting to choose to enter their spaces and initiate interactions in the first place (M. Brown, personal communication, December 11, 2023). We should also ask ourselves what our motivations are for entering their space. And, as mentioned earlier, who’s benefitting and who’s potentially at risk of being harmed if we bring visitors into their space? If we believe it’s still worth it for visitors to enter their space after reflecting on these questions, we should observe how the residents respond as we approach. Do they move towards the gate with loose, bouncy bodies, or do they stiffen up and watch us from a distance? Do they move away further into their pasture? These are behaviors we often take for granted, but they’re how other animals communicate consent or withhold it.

Reflection Questions

Envision one of the residents at your sanctuary. How do they communicate consent and non-consent during interactions? What factors may influence their desire to engage with visitors on any given day?

Based on our knowledge and observations about the residents, as well as the essential insights their caregivers provide, we can collectively determine whether visitors should have the opportunity to engage with the residents directly (without a barrier). If so, it’s especially crucial to let the residents take the lead in determining how the interaction will unfold. This requires that we stay present with the animals and observe their body language and behavior closely. It also requires that we remain mindful of how our own behavior and body language are being interpreted by the residents. This allows us to enter into a true conversation with them.

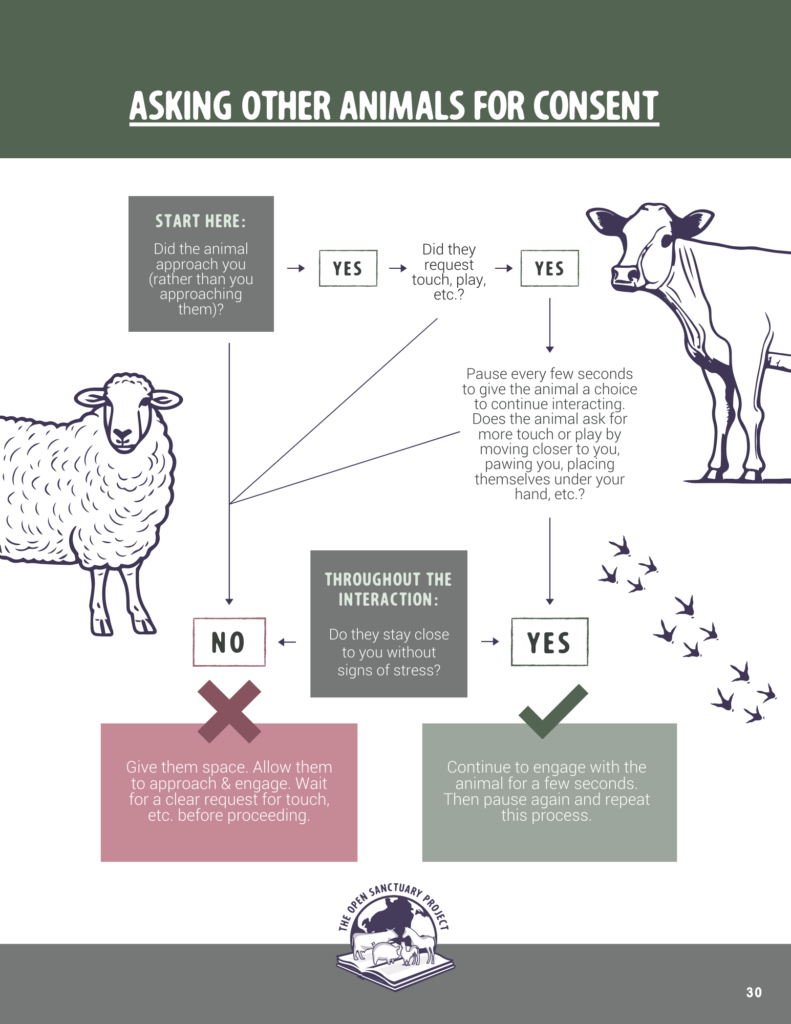

While there’s much nuance and complexity that occurs in these consent-informed conversations, the graphic on the following page can serve as a general guide that can be shared with staff, volunteers, and visitors. The graphic highlights how consent is dynamic; whether or not an animal consents to an interaction changes from moment to moment. We shouldn’t assume that a resident who’s usually friendly and wants to engage will feel like that every day and in every moment. For example, a turkeyUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated turkey breeds, not wild turkeys, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource. who often chooses to get in someone’s lap to be touched may not be as keen to do so while they’re molting.

Download the Graphic Below!

Click here to download the graphic below so you can print and share! You can even provide the handout to visitors and encourage them to go home and practice consent-based interactions with their companion animalsAnimals who spend regular time with humans in their home and life. Typically cats and dogs are considered companion animals, though many species of animals could also be companion animals.. Then, you could ask visitors to report back (such as via social media) on how it went and what they learned. This can help visitors take what they learn at the sanctuary and integrate it into their daily lives.

Rather than making assumptions about whether a resident will consent or not to engage with visitors, a good guiding principle is that if it’s not a clear yes at any given moment, it should be interpreted as a no. And a no means to give that resident space to decide and guide what the rest of the interaction will look like. This approach decreases safety risks and increases the likelihood that the resident’s agency and well-being are supported. To view an example of what a clear yes looks like, take a look at the video below!

As you’ll see in the video, residents will often actively seek out the kind of attention and affection they are looking for if given the chance. They may paw at or nudge people’s hands with their heads. They may position their bodies to indicate where they like to be massaged. Creating space for this level of communication between the residents and the visitors can be impactful and may empower humans to engage in consent-based interactions with all animals they interact with, inside and outside of the sanctuary. These are basic skills that can be applied across species and individuals.

Although they’re not foolproof, nor are they a substitute for staff and volunteers to learn about individual and species-specific behavior, we can teach visitors about the value of:

- Keeping distance/creating space

- Allowing animals to approach you rather than you approaching them

- During interactions, taking frequent breaks

To Feed or Not to Feed?

To feed or not to feed (during visits)? This is a question many sanctuary educators grapple with. When deciding whether or not we should have visitors feed nutritional treats to residents, we should consider factors such as the specific health needs and dietary restrictions of each animal as well as interspecies relationships and social dynamics. Sometimes, the presence of food can increase arousal and potentially cause conflict between the residents. From an agency perspective, some animals who want to engage with the visitors or enjoy treats may not be able to because they might be pushed away by the more food-motivated residents. It’s also important to consider how this practice might impact residents who are unable to retrieve treats due to mobility issues, other disabilities, and social dynamics. In other situations, a resident may be afraid of humans, but their motivation to obtain food may override this, creating emotional conflict within the animal and risking a negative experience. Some residents may also behave in ways that are unsafe when food is involved, such as jumping on the visitors or taking treats with hard mouths.

Some ways to mitigate these potential problems include:

- Having food of equal value available away from visitors to give residents a true choice

- Using remote feeders or feeding stations rather than hand-feeding (e.g., Visitors can put treats down a PVC pipe to have a resident collect a few feet or more away. This is especially helpful for residents who are worried about humans and would prefer some distance.)

- Creating space between the residents when treats are present by tossing treats in different directions or having visitors spread out when feeding

- Using food that is less arousing (e.g., For goats, this might be having visitors feed them fresh clover or dandelion rather than commercially made treats.)

While feeding treats can create positive associations with humans, sanctuary educators must also consider if this practice ultimately benefits the residents and what hidden messages it may send to visitors. From a visitor’s perspective, what are the differences between feeding other animals in a sanctuary setting versus in a petting zoo setting? How do sanctuary educators ensure this practice does not perpetuate nonhuman exploitationExploitation is characterized by the abuse of a position of physical, psychological, emotional, social, or economic vulnerability to obtain agreement from someone (e.g., humans and nonhuman animals) or something (e.g, land and water) that is unable to reasonably refuse an offer or demand. It is also characterized by excessive self gain at the expense of something or someone else’s labor, well-being, and/or existence. for human entertainment? Reflecting on these questions, potentially in collaboration with our visitors, could be illuminating and impactful.

Planning Ahead

It’s important to plan ahead and set our residents up for successful interactions with visitors. For example, in addition to ensuring that visitors don’t bring unapproved food into enclosures with them, it can also be important to make sure they don’t have dangling items (like things hanging from their purses) that residents might be tempted to chew on and possibly consume. Of course, this is important from a resident health perspective, but it’s important for agency and consent, too. By knowing our residents and planning ahead, we can avoid situations where we have to then inhibit their agency if they attempt undesirable behavior like eating someone’s scarf. Also, this takes into account the agency and consent of the visitors, as they likely would not consent to their things being eaten!

Reflection Questions

In what ways do you plan ahead to set resident-visitor interactions up for success? In what ways can you improve upon this?

Agency and Consent Offsite

Some sanctuaries may be considering bringing residents to offsite events to bolster their education and outreach efforts. There are several crucial considerations to make prior to doing this. Firstly, it’s important to consider how you will interpret and determine whether or not a resident is consenting to traveling and being brought offsite. There are many elements that make up these experiences that residents must be comfortable with, such as the transportation process, being in a different and often unpredictable environment, and interacting with unfamiliar people. While some residents may be comfortable with each of these, others are not. Determining whether a resident consents to partaking in such experiences requires a very careful understanding of their behavior and body language as well as consistent monitoring for non-consent, stress, and other negative health implications.

We must also check our biases and ensure our desire to take an animal offsite doesn’t cloud our ability to judge whether or not it’s something the resident wants. Since this is not always a particularly easy task, another important question we should ask ourselves is whether or not bringing them offsite is truly to their benefit and even necessary. If the answer is no, in what ways can you provide engaging and enriching educational opportunities for folks you meet at offsite outreach events that do not include the residents?

If you are able to determine that a resident is clearly saying no, it’s important to respect that decision. If you are unable to determine whether a resident is saying yes or no, that should be interpreted as a no, and it’s important to respect that as well.

What are the communicative cues that your companion expresses that indicate they consent to the following?

- leaving their living space

- getting into and being secured in a vehicle

- being in a new environment and interacting with new people

What are the communicative cues or signs of stress that indicate that they are no longer consenting to the above?

Clearly identifying and appropriately responding to these cues is essential!

Best Practices for Ensuring Safety and Supporting Agency Offsite

If you are able to determine that a resident is clearly saying yes to going offsite, there are some important factors to consider prior to and during the event. Explore these below!

- For the residents who do truly enjoy traveling and meeting new people, it’s crucial to ensure that the setting away from home is comfortable and safe for them prior to bringing them there. Check the event site beforehand and plan accordingly. Is the site close to home? Proximity to home is very important. It’s also critically important to check the weather beforehand and plan accordingly. For example, if it’s sunny, is there shade for the residents?

- Ensure that the human(s) traveling with the resident knows the resident and has a deep understanding of their individual and species-specific needs, as well as what non-consent, distress, and agitation look like for them.

- Determine if a resident would prefer to travel with a companion, and if so, make sure all are comfortable at all times.

- Ensure a safe and stress-free transportation experience.

- Maintain a regular food and water routine.

- Consider the sounds, sights, smells, and other sensations residents will be exposed to and take measures to prevent sensory overstimulation.

- Provide safe space(s) for them to retreat and hide at all times.

- Offer opportunities for decompression and providing space and time for undisturbed rest.

- Teach each person who engages with the animal how to ask for consent (see p. 30).

- Be prepared to go home at any moment if that’s what the resident wants and/or needs.

- Supervise residents at all times and avoid potential dangers.

- Implement protocols to prevent escape.

- Have a species- and individual-specific first aid kit(s) on hand in case of emergencies.

The same consent-based practices for onsite experiences and interactions should be applied offsite. In each interaction we facilitate with residents, we should ask ourselves: “In this moment, is this interaction supporting or suppressing resident agency?” If we determine their agency is being suppressed, the next question we should ask ourselves is, “In what ways can I support this resident’s agency instead?”.

A Word of Caution

Residents that are at any increased risk of stress, illness, or injury, including those who are already sick or injured, babies, elderly residents, animals with general anxiety, and new rescues, among others, should not be brought offsite, except for the purpose of healthcare or emergency. We also advise against bringing any species who are at an increased risk due to any biosecurity threats (e.g., HPAI and RHD) outside of their homes and allowing them to interact with human visitors to ensure their safety and the safety of humans.

There’s a lot to take into account when you are determining whether or not to take a resident offsite. As a general guiding principle, if there’s the slightest bit of concern for their physical or mental well-being and safety before and during the event, and/or if they’re not expressing clear consent to go and remain offsite at any time, they shouldn’t be taken away or kept from their home for any reason except for the purpose of healthcare and emergency.

A Note About Resident Roles

A common practice in sanctuaries is for staff and volunteers to ascribe particular roles to residents, such as the role of “ambassador” (Blattner et al., 2020). It’s important to consider the potential impacts this may have. For example, ambassador residents are meant to represent entire groups of animals. What are the advantages and disadvantages of this? How might various roles shape how individuals are treated or how their species are perceived? How might ascribed roles shape the ways visitors expect to engage with them onsite? When determining if and how to ascribe roles to residents, we should consider how to prioritize both the individual and collective agency of our residents and the other animals they may represent.

One approach to sanctuary education that aligns with these considerations is to note the nuance of the very complex systems that farmed animals are affected by and highlight how each individual has their own unique stories that are worth knowing and respecting. In addition to examining the roles we may impose on residents, it’d also be beneficial to reflect on how we can let residents choose for themselves the roles they want to embody and how we might support them in doing so (Blattner et al., 2020).

Reflection Questions

Have any of your sanctuary’s residents chosen roles for themselves, such as guardian or greeter? In what ways might you support them in these roles?

Human Considerations

So far, we’ve explored how the environment and resident-specific factors can influence how residents express their agency during sanctuary education. Especially during onsite events, humans can also significantly impact resident agency. For example, if conducting a group visit, one thing to take into account is the number of visitors. Larger groups of visitors will likely affect the agency and well-being of residents differently than smaller groups. The age of the visitors is also crucial to consider. From an agency perspective, residents may have varying levels of comfort with children, which may influence whether or not they consent to engaging with them. This will shape their behavior towards children. For instance, a particular sheep or goat may be especially interested in head-butting children, which poses a safety risk and may also indicate that the presence of children isn’t something they consent to. Establishing guidelines such as requiring that all young children are behind a barrier when interacting with residents can help prioritize the agency, safety, and well-being of both the residents and visitors. Some sanctuaries also have family-focused visits and events that are carefully planned to ensure safe and enjoyable experiences for everyone.

The visitor-to-educator ratio is another important factor to consider. With a group of visitors, having more than one educator co-lead the visit can create a more engaging and conversational atmosphere. It also allows for practical benefits, such as one person assisting with opening gates while the other guides the visitors. Additionally, having multiple staff and/or volunteers involved with visits enables better observation of the residents for signs of non-consent. As mentioned, non-consent may present as behavior that may put the safety of others at risk, especially if they’re interacting with children or visitors with disabilities. Sanctuary educators need to not only be aware of the individual animals closest to them but also remain in tune with the comfort level of everyone else who’s in the space they’re in. This highlights how helpful it can be to have multiple staff or volunteers involved during guided visits, especially with larger groups, to ensure that the agency and well-being of all residents are supported.

It’s also essential to take into account that sanctuary visitors are humans with their own experiences, struggles, and biases that they’re bringing with them to the sanctuary. All of the above may influence their interactions with the residents. Being cognizant of this and aiming to create a calm, welcoming, and gentle environment is paramount.

The pace and length of educational events also play a role. For example, large groups and short visit durations can result in an experience that feels rushed for both staff and visitors. This might make it challenging to prioritize the agency and consent of the residents, which is a practice that requires slowing down and being present with the animals. On the flip side, longer visit durations come with their own challenges in regards to maintaining visitor engagement, accessibility, resident agency, and more.

It’s also critical to set clear expectations for visitors prior to their visit. This can help avoid misunderstandings and promote safety and well-being for all. It’s important to communicate that the sanctuary is not a petting zoo. As sanctuaries dedicated to disrupting traditional ways of viewing other animals, we can make it clear that we don’t expect animals to behave in a certain way for human benefit. We don’t expect that the residents are ever “available” for visitor viewership and pleasure or that visitors have the right to just walk up to and impose themselves on residents. Disclaimers and additional information about this can be provided on the website, in booking emails, and throughout educational programs and events to reinforce this messaging.

These are just a handful of the considerations related to humans that are worth reflecting on. However, through having knowledgeable staff/volunteers, setting clear expectations, and prioritizing safety and resident agency, sanctuaries are well on their way to having impactful educational experiences that align with their mission.

Reflection Questions

What do your sanctuary’s visitors and learners expect from your educational programming? Would agency-centered sanctuary education change what they experience? How might your sanctuary set clear expectations in advance of your programming about visitor-resident interactions and experiences?

Alternative, Agency-Centered Forms of Sanctuary Education

As your sanctuary explores the various paths to prioritizing resident agency and consent during educational programs and visits, it’s helpful to consider alternative ways for visitors and supporters to have influential experiences that don’t rely solely on touching or being in close proximity to the residents. There are a variety of activities and events that members of the public can take part in that still provide possibilities for connection with the residents but are less likely to impact resident agency and well-being in ways we strive to avoid.

For example, maybe a resident doesn’t like to be touched, but they enjoy playing with humans. Visitors can be instructed on how to play with them safely, such as by tossing a cow’s favorite ball into their pasture for them to chase while remaining on the opposite side of the fence. Visitors can participate in providing enriching experiences for the residents in many other ways, too. They can fill food puzzle toys, craft other enrichment items, or locate natural browse (such as fallen branches of trees that are safe to consume) to share with the residents.

Providing residents with enrichment and space to engage or not also provides outlets for them to decompress if they experience stress from the presence of visitors. One way we could do this is by including a fun variety of safe resident- and caregiver-approved enrichment items (such as playground equipment for goats) in pastures and enclosures that visitors can observe the animals interacting with.

From an educational standpoint, it’s beneficial for visitors to see formerly farmed animals enact their agency and engage in positive species-typical behaviors for multiple reasons. As we’re observing these behaviors, we can point them out to visitors and, as applicable, mention how farmed animals might not get the opportunity to engage in those behaviors in traditional farm settings. For example, most hens used in the egg industry don’t have the opportunity to dust-bathe or stretch their wings. Similarly, many cows exploited by the dairy industry aren’t able to graze. Even being outside is something many animals might not experience in modern agricultural settings. As sanctuary educators, we can also highlight social interaction between residents, how important it is to their well-being, and how it’s something they should have the freedom to engage in.

Engaging in mindful, agency-centered observation of residents is another way that visitors can experience sanctuary. They can simply sit and watch residents from a distance to learn more about who residents are as individuals, what their relationships are like, etc. This deepens empathy for residents while also benefiting the emotional health of visitors by encouraging them to slow down and be present. However, even this activity isn’t without the possibility of harm. During onsite sanctuary research, a team of researchers noted that some of the residents didn’t approve of being stared at by the researchers while they were observing and taking notes (Blattner et al., 2020). If we, as sanctuary educators, are facilitating mindful resident observation, it’s important to notice which residents might be uncomfortable with strangers observing them and who don’t seem to mind. Some residents may even be genuinely curious about humans watching them from a distance and may decide to engage. This speaks to how crucial it is to be cautious about approaching sanctuary education with a “one size fits all” mindset. Agency-centered education requires frequent adjustment of our lesson plans and educational activities based on what residents are telling us about what they’re comfortable with at any given moment.

Other options for sanctuary education that support farmed animal agency and well-being include events that don’t involve interacting with the residents at all. This can include hosting educational workshops or classes on various topics either in person or online. It could also include sharing videos and photos of residents as well as their stories on social media, in classroom presentations, etc. The possibilities are endless!

Navigating Barriers

It’s important to be aware of the potential barriers to fostering resident agency in sanctuary education. Lack of resources, such as financial resources, number of staff/volunteers, time, and more always present challenges in sanctuary settings, and education is no exception. A lack of resources can put more strain on some sanctuary educators, especially those who are involved in other aspects of the sanctuary. Prioritizing resident agency often means slowing down, which is challenging to do if we’re dealing with other stressors. Also, in the context of sanctuary education and outreach, there are complex social factors that come into play, such as an innate need to please visitors, the desire to provide a fulfilling experience, and the pressure to garner donations. Sometimes, these factors may shift our focus away from the needs, agency, and comfort of the residents. Agency-centered sanctuary work is also at odds with everything we’ve been conditioned to believe about other animals, especially farmed animals. We must be very intentional in our practices in order to resist reproducing oppressive power dynamics that position human needs and desires always above those of nonhumans.

Critical reflection is vital in navigating these barriers. For example, if you have a limited number of staff to assist you during guided visits, it may be helpful to reflect on how you can organize and prepare ahead of time to set each visit up for success. How might you facilitate these visits in a way that makes it possible to prioritize resident agency and well-being without additional help from other staff or volunteers? Would modified routes or other alternative practices be beneficial in achieving this goal? Could a different type of education program be a better fit for your sanctuary, given the number of staff and/or other resources available to you? This program could be entirely unique from a more traditional guided visit and could be developed in a way that requires fewer staff members and enables you to prioritize resident agency more manageably. These are just a few considerations worth reflecting on. We’d also greatly benefit from more sanctuary research to uncover additional strategies for overcoming these barriers and ensuring sanctuary education truly centers the agency of farmed animals.

Reflection Questions

What barriers do you and your sanctuary face in fostering agency during your educational programs and outreach events? How might you navigate these?

Interested in Learning More?

Interested in learning more about fostering farmed animal agency and consent in sanctuary education? Please click here to read the fifth part of this guide!

We’d Love to Hear from You!

This guide is a living document that we plan to make continual changes to as we get feedback from sanctuary staff and volunteers who have implemented what they’ve learned from this guide into their sanctuary education practices. In our efforts to ensure this guide is as helpful as possible to sanctuary staff, volunteers, visitors, supporters, and, most importantly, the residents, we’d love to hear how this guide has impacted your work. If you have feedback, please contact us here!

Sources

A Guide to Fostering Farmed Animal Agency in Sanctuary Education | The Open Sanctuary Project

In-Person Sanctuary Educational Programming: What Are Your Options? | The Open Sanctuary Project

Predator-Proofing for Bird Residents at Your Animal Sanctuary | The Open Sanctuary Project

Communicating with Youth About Animal Exploitation | The Open Sanctuary Project

Time to Thrive: The Importance of Enrichment | The Open Sanctuary Project

Observation: An Important Caregiving Tool | The Open Sanctuary Project

Nutritional Enrichment at Animal Sanctuaries | The Open Sanctuary Project

The Differences Between an Animal Sanctuary and a Petting Zoo | The Open Sanctuary Project

Biosecurity Part 1: Introduction | The Open Sanctuary Project

HPAI Biosecurity Plan and Checklist | The Open Sanctuary Project

Advanced Topics in Resident Health: Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease | The Open Sanctuary Project

What to Consider When Children Visit Your Animal Sanctuary | The Open Sanctuary Project

Fostering Empathy Towards Farmed Animals | The Open Sanctuary Project

Virtual Sanctuary Educational Programming: What Are Your Options? | The Open Sanctuary Project

All About Social Media for Your Animal Sanctuary | The Open Sanctuary Project

How to Develop a Fundraising Plan for Your Animal Sanctuary | The Open Sanctuary Project

Fostering Critical Thinking at Your Animal Sanctuary | The Open Sanctuary Project

Saving Animals: Multispecies Ecologies of Rescue and Care | Elan Abrell

A Farm Sanctuary Tour’s Effects on Intentions and Diet Change | Tom Beggs and Jo Anderson

Animal-Informed Consent: Sled Dog Tours as Asymmetric Agential Events | David A. Fennell (Non-Compassionate Source)

Non-Compassionate Source?

If a source includes the (Non-Compassionate Source) tag, it means that we do not endorse that particular source’s views about animals, even if some of their insights are valuable from a sanctuary perspective. See a more detailed explanation here.