If you care for nonhuman animals, understanding how they learn is vital for a happy, safe life in a sanctuary environment. We’ve all been there: You need a particular resident to carry out a certain behavior, such as coming inside for the night or standing still so you can trim their nails! Whatever it may be, they are hesitant, maybe even actively resistant. Learning theory can help caregivers approach these situations, teaching residents in a way that alleviates discomfort, fear, or concern. While there is much to cover in learning theory and its application in sanctuary environments, this resource will act as a foundation, covering some basic concepts you can apply to your teachable moments with residents. It might help you identify why one scenario was unsuccessful, but another had a positive turnout and how you might approach the situation differently in the future. This resource is part of a series on resident behavior. If you haven’t read Behavoir 101, we recommend doing that first. Look for future resources with detailed guides on specific aspects of behavior, including teaching and learning. Understanding how residents learn can make a huge difference in their day-to-day lives AND yours!

Reevaluate Human-Animal Relationships

At the Open Sanctuary Project, we try to be aware of how language can affect how we see the world and interact with those within it. This has prompted us to choose the word “teach” in place of “train.” This is partly due to the association of the word “train” with exploitive human-animal interactions that center human desires. This isn’t to say that all individuals using the word use the same philosophy or exploitative mindset. There are many human individuals who, in spirit, are accomplishing good things for and with animals and may use the term “training.” However, even this falls short of expressing the intention behind it.

The intention is that we (human animals) shift our perspective in regard to human-animal relationships. As a species, we have constructed a hierarchy with human animals at the top and nonhuman animals lower in the hierarchy, their place in it often depending on their similarity or “closeness” to human animals. We want to dispel this notion, and what better place to do this than in a sanctuary environment where human animals and nonhuman animals interact daily, with the human animals working to improve the lives of the nonhuman animals at their sanctuary and in the world in general? We encourage you and other staff to think about your relationship with residents as one that allows for individualism, autonomyThe ability for individuals to have access to free movement, appropriate food, and the ability to reasonably avoid situations they wish to avoid., and “dialogue” of a sort. Work with residents. Consider them in their personhood and build a teaching relationship where you both learn from the other and strive to attain communication and understanding whenever possible.

Teaching And Learning Is About Communication

So how do we communicate effectively with residents? How do we effectively communicate voluntary participation? Safety? What do we want them to do? Whether a learning experience is positive, negative, or neutral depends on a number of factors, some of which are within a caregiver’s control. Understanding concepts of learning theory can help.

Teaching in a sanctuary context is really about communication. Teaching residents should be about building a relationship with a resident and establishing a dialogue, with caregivers communicating what action is desired and that the requested action will result in neutral or positive outcomes, allowing the resident choice and autonomy whenever possible.

It can be easy to simply expect residents to do what you need them to do. This is because you know what you are asking and why. You also know it is safe for them. However, they don’t have that information. Residents need to know what we are asking of them and whether it is safe, neutral, or has positive outcomes. I don’t know about you, but I don’t like doing something just because someone tells me to unless I understand what is happening and what is being asked of me!

Every Interaction Is A Learning Opportunity

Although making time to have focused learning sessions with residents is vital, don’t forget that every interaction with them is a learning opportunity. In fact, sometimes residents may learn something opposing the overall message we were hoping to communicate. Something as simple as having a walkie-talkie go off loudly while evaluating someone’s hooves could create a negative association if this frightens a resident. This is why, as caregivers, we must do our best to reduce fear and promote positive, or at least neutral, emotional states whenever possible. We aren’t perfect, and it isn’t always possible through no fault of our own. Give yourself grace when an interaction is less than ideal and stop and reflect on where something went wrong and how you might improve future interactions. Be understanding of why a resident may be reluctant to participate. Communicate with your team about those interactions so they can also approach future interactions with the resident more successfully.

Reframing Resident Behavior

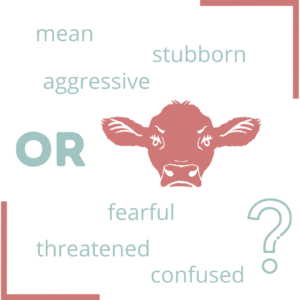

In moments like those listed above, it is easy to label a resident as “stubborn,” “untouchable,” or “mean.” However, residents have a reason for behaving the way they do, sometimes very good reasons based on their experiences and perceptions. Labeling a resident can affect how other caregivers and volunteers see them and can then go on to affect the level of care they are receiving. An “untouchable” horse may have had a fearful response to something in the environment, causing them to rear back and panic. Take a moment to observe what was happening in the environment and reflect on why they may have acted as they did. Going on to label them as “untouchable” can discourage others from interacting with them or may cause them to approach a resident with fear instead of caution. The resident may then pick up on this fear, perpetuating the state of discomfort. This, in turn, can affect their behavior. Simply put, it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. When recounting an interaction with other caregivers, do so step by step, keep to the facts, and avoid using labels. This can help ensure everyone is safe while also working towards solutions and a better understanding of the resident as an individual.

When we struggle to load a resident, perform a health checkThe Open Sanctuary Project uses the term "health check" to describe health evaluations performed by caregivers who are not licensed veterinarians. While regular health checks are an important part of animal care, they are not meant to be a replacement for a physical exam performed by a licensed veterinarian., or even enter their living spaceThe indoor or outdoor area where an animal resident lives, eats, and rests., it can be easy to label a resident as “stubborn” or “aggressive.” Unfortunately, residents may even be dismissed as not being very smart when they fail to respond in the way a caregiverSomeone who provides daily care, specifically for animal residents at an animal sanctuary, shelter, or rescue. wants them to. However, there are many reasons why a resident may not want to do what is asked of them. These feelings may be related to fear, uncertainty, confusion, self-preservation, frustration, suspicion, disinterest, discomfort, or just not understanding what you are communicating to them. It is our job as caregivers to learn what may be causing the issue and find a way to communicate to them (teach them) what is being asked. It is vital to teach them that they are safe. Teaching them there is a benefit (or at least no harmThe infliction of mental, emotional, and/or physical pain, suffering, or loss. Harm can occur intentionally or unintentionally and directly or indirectly. Someone can intentionally cause direct harm (e.g., punitively cutting a sheep's skin while shearing them) or unintentionally cause direct harm (e.g., your hand slips while shearing a sheep, causing an accidental wound on their skin). Likewise, someone can intentionally cause indirect harm (e.g., selling socks made from a sanctuary resident's wool and encouraging folks who purchase them to buy more products made from the wool of farmed sheep) or unintentionally cause indirect harm (e.g., selling socks made from a sanctuary resident's wool, which inadvertently perpetuates the idea that it is ok to commodify sheep for their wool).) in participating can make a world of difference.

We talk a lot about teaching residents what we want, but a big part of successful caregiving is learning! It is imperative to learn who the residents are as a species and as individuals. How do they communicate as a species? As an individual? (Think behaviors, vocalizations, and body language!) What makes them feel safe and comfortable? We often ask a lot of residents in order to provide them with the best care. Some of that care may be aversive to them, such as health checks or procedures, restraint, grooming, loading, and even simply accepting touch.

Example: Samuel the donkey is resistant to being loaded into the trailer. This is not a bad attitude problem! This is merely Samuel’s sense of self-preservation to avoid the danger of the unknown (or discomfort of the known!). The caregiver must address Samuel’s discomfort with the trailer in a way that respects and considers Samuel’s needs and emotional state.

Let’s take a look at some of the concepts of learning theory and briefly touch on how these might apply in sanctuary environments:

Types Of Learning

Insight Learning

Insight learning happens when someone has an “aha!” moment or a sudden understanding of the problem and solution. A common example of this in nonhuman animals is tool-making. For example, a crow, when presented with a narrow tube of water containing a floating food item at the bottom, will assess the situation and then have an “aha!” moment. The crow will then add pebbles to the tube, understanding this will cause the water level to rise and bring the treat close enough to grab. This isn’t something they instinctively knew how to do.

Associative Learning

Associative learning is where someone makes associations between two events or stimuli in their environment. The three types of associative learning are classical conditioning, operant conditioning, and observational learning:

Observational Learning

Observational learning is just what it sounds like: Someone sees someone performing an action and learns how to do the same themselves, or in some cases, learns how to avoid doing something that they observed led to a negative outcome.

Here is a video example of observational learning in horses:

Classical Conditioning

Classical conditioning occurs when someone associates one stimulus with another stimulus after repeated exposure. This is feelings-focused learning.

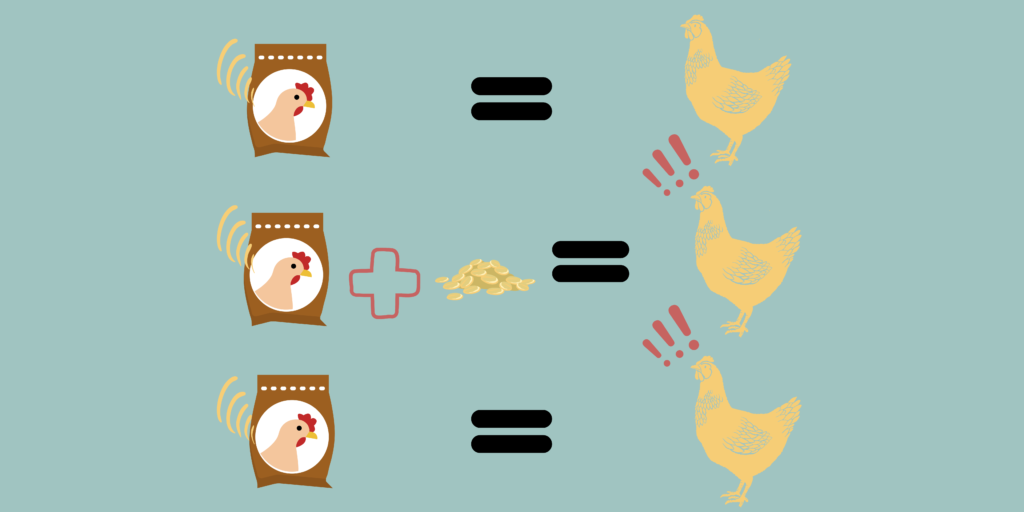

Here is a visual example of the basic concept of classical conditioning, demonstrating how:

At first, a neutral sound (the sound of a food bag crinkling) doesn’t initially elicit a physiological or emotional response from Mr. Hobbs the chicken.

However, when the neutral sound is paired with the presence of food, the sound will later elicit an excited response when Mr. Hobbs hears the sound of a food bag, whether or not food is actually present.

Here is a video that uses a similar example but goes deeper into the topic:

Operant Conditioning

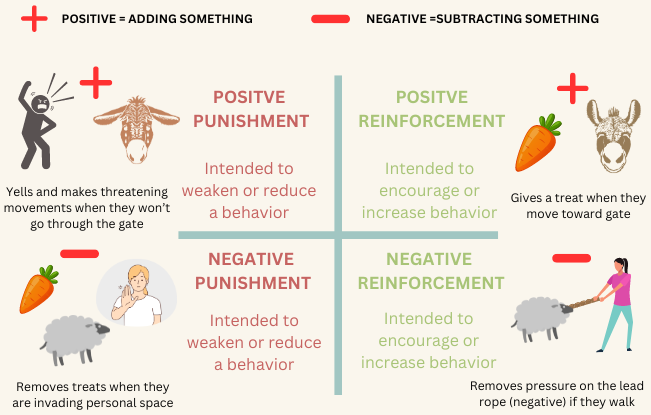

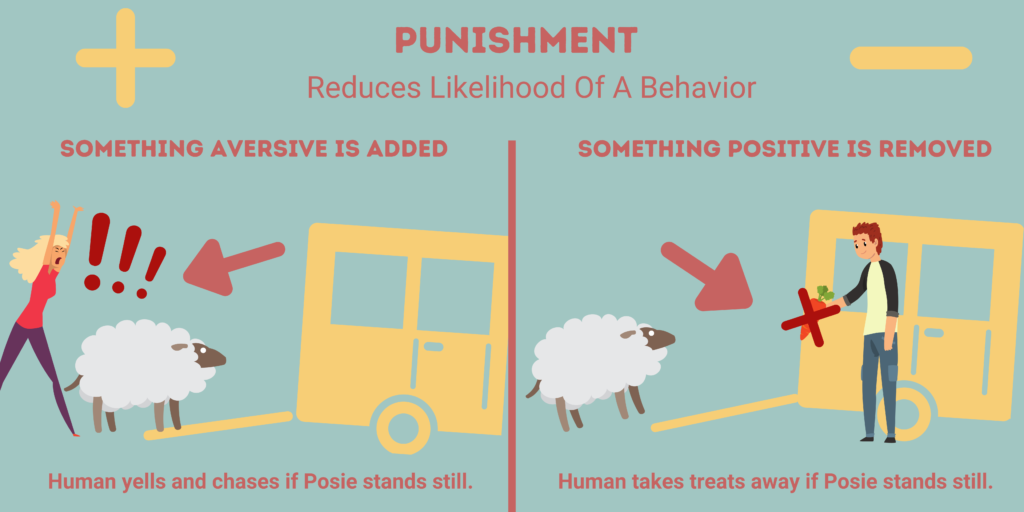

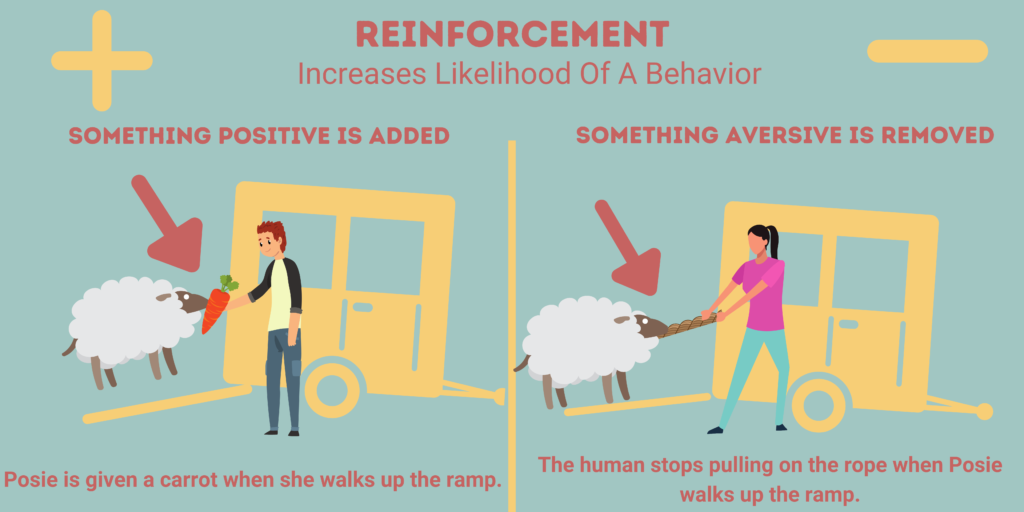

Operant conditioning is different from classical conditioning, as it occurs when someone learns to complete or increase a certain behavior or cease it because their behavior is reinforced or punished. There are two types of reinforcement and punishment: positive and negative. It is important to note that, in the context of operant conditioning, the word “positive” means added, and the term “negative” means subtracted or removed. In this context, positive doesn’t mean good, and negative doesn’t mean bad. See descriptions of each below and refer to the graphic to better understand how operant conditioning works:

Positive reinforcement is when you give something pleasant to encourage or increase a certain behavior.

Negative reinforcement is when you remove something aversive to encourage or increase a certain behavior.

Positive punishment is when you add something aversive to reduce or stop a behavior.

Negative punishment is when you remove something that is considered pleasant to reduce or stop a behavior.

Let’s look a little closer at these two concepts in learning theory.

Punishment

A punishment is something that decreases the likelihood of a behavior being performed in the future. Within learning theory, this vocabulary expands upon the common idea of punishment and has different meanings and uses. Positive punishment is when you add something aversive to stop a behavior. Negative punishment is when you remove something that is considered pleasant to stop a behavior.

We will go further into punishments in future resources in order to address what is and isn’t appropriate in a sanctuary context. Many forms of positive punishment are inappropriate within a sanctuary environment, though there are a few careful exceptions.

Reinforcer

There are negative and positive reinforcers within learning theory, just as there are negative and positive punishments. A reinforcer is something that increases the likelihood of a behavior being completed in the future. Positive reinforcement is when a behavior is rewarded with something pleasant. Negative reinforcement is when something aversive is taken away when a behavior is completed. We will go further into reinforcers in the next resource on this topic and how reinforcers can be appropriately used in a sanctuary context. See the following graphic for an example of positive and negative reinforcement:

Counter Conditioning

Counter conditioning is the practice of teaching someone that the thing they once found adverse is, in fact, neutral or even positive, eliciting a different physiological/emotional response, with the goal being a change in behavior. You can think of classical conditioning as more of an internal change and operant conditioning as an external change, although operant counter-conditioning automatically involves classical counter-conditioning, as the individual will learn to associate the stimulus with a different stimulus and have a different emotional/physiological response, as well as perform a trained behavior when exposed to the stimulus.

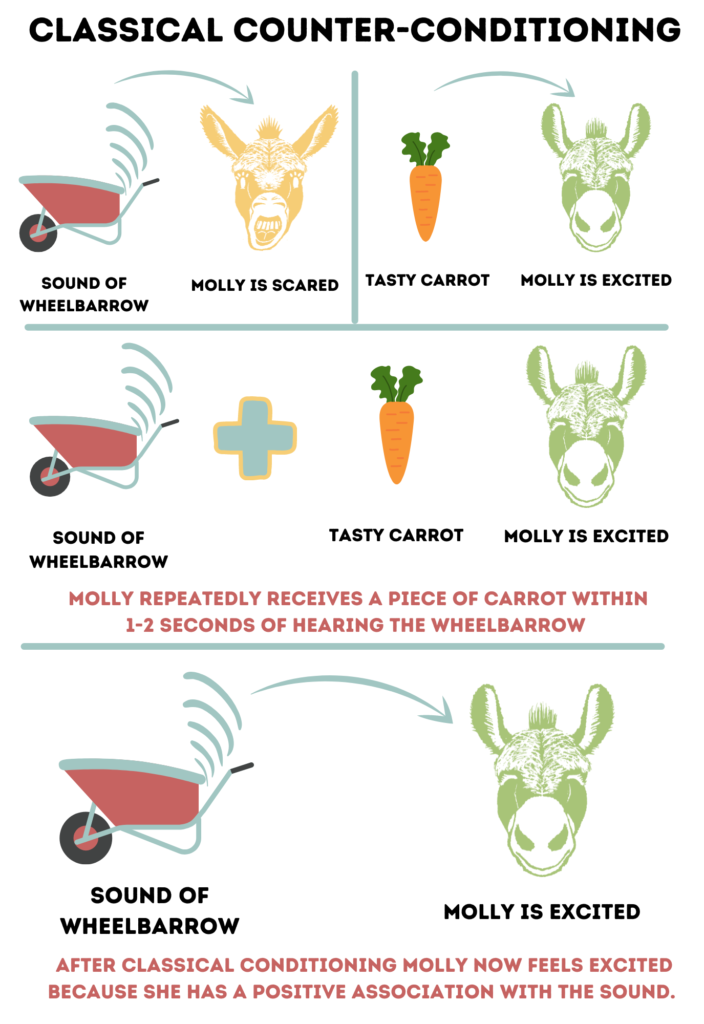

Classical Counter-Conditioning

Classical counter-conditioning consists of teaching someone to associate a certain stimulus (usually something eliciting negative responses) with a different stimulus (usually one that elicits positive responses) and respond differently emotionally, and physiologically in response to the original stimulus.

Operant Counter-Conditioning

Operant counterconditioning focuses on teaching someone to complete a different behavior than they currently do in response to a stimulus, specifically a behavior that is incompatible with the original behavior. Simply put, teaching a new behavior to replace the old behavior.

In the above example of Molly being fearful of the wheelbarrow, you’ll notice nothing is said about any actual behavior. Rather, the focus is on changing Molly’s feelings about the presence of the wheelbarrow. As an example of operant counter-conditioning, say that Molly charges the fence whenever she sees the wheelbarrow, making it difficult for caregivers to open the gate and enter with it. Caregivers not only want Molly to feel emotionally better when she sees the wheelbarrow, but want her to carry out a different behavior when she sees the wheelbarrow. This would be a time to consider operant counter-conditioning.

Generally speaking, operant counter-conditioning involves using positive or negative reinforcers or positive or negative punishments to bring about a change in behavior. Perhaps they want Molly to move or stay away from the gate when entering with the wheelbarrow. An example of operant counterconditioning would be teaching Molly to go and wait at a certain part of her living space when she sees the wheelbarrow. Her caregiver would work with her, ideally using positive reinforcement, to replace charging the fence behavior when the whee barrow goes by to walking to a place and remaining stationary, which is reinforced by providing treats. We will also discuss what aspects may or may not be acceptable at a sanctuary.

Glossary Of Relevant Terms

Here are a few related terms that will pop up in this series about learning and teaching in a sanctuary environment. Familiarizing yourself with them will help you build a solid foundation as we get more in-depth in future resources.

“Teaching can be defined as engagement with learners to enable their understanding and application of knowledge, concepts, and processes.”

For example, if Francine the rabbitUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated rabbit breeds, not wild rabbits, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource. likes to eat up all her breakfast then run over to Gimly’s bowl and gobble up all his breakfast, simply changing their feeding setup by separating them until both have finished can address the issue and doesn’t require staff to try and modify Francine’s behaviors through behavior modification techniques.

In another example, if Gimly hides every time he sees a carrier knowing it portends a visit to the vet, staff can use behavior modification techniques to reduce Gimly’s fear of the carrier by associating it with something positive.

An example: Molly the donkey startles when the new wheelbarrow is pushed past their outdoor living space. Over time, they learn that the wheelbarrow is not a threat and become habituated to the sound and sight of it. It is important to note that if the situation shifts in some way, the original response may return. For example, if the wheelbarrow suddenly has a squeaky wheel, Molly may find it frightening again due to the unexpected sound.

Think of a rating system of anxiety or fear-producing stimulus, ranging from 1 to 10. In desensitization, you would start at a 2 or 3 and eventually increase exposure to a 9 or 10 of the stimulus, but by this point, the individual will not find this level of exposure anxiety-inducing, or at least not nearly as much.

Upon learning Molly is scared by the sight/sound of the wheelbarrow, staff slowly move the wheelbarrow closer from a far distance over days or weeks while the resident becomes desensitized to it. Basically, the aversive stimulus, in this case, a wheelbarrow, is slowly introduced at lower levels, gradually building up to closer spaces, such as wheeling it by the resident without a fear response.

Species Vary In How They Learn

What a species eats, whether they are a prey animal or a predator (or both!), how they reproduce, what environment they live in (water, dense forest, desert, treetops), whether they fly, burrow, or nest, what their social groupings look like, and much more, can all affect how a species learns. Some species have evolved to learn well by watching others of their own species, some have learned to solve puzzles on their own, others still make associations quickly between their observations of a situation. It is important to learn about the species you are working with and how they navigate the world and their environment. This can help you tailor learning sessions for resident species and ensure more successful communication.

Everyone Is An Individual

Don’t forget that, while species have generalized behaviors, preferences, and abilities, every resident is an individual. It is vital to learn about who they are, in addition to “what” they are. Everyone has a history, genetics, and personality that affects how they move through the world. Keeping this in mind while creating learning opportunities will help ensure successful encounters.

We hope this helps familiarize you with some of the language and concepts surrounding learning and teaching in a sanctuary context. Stay tuned for more resources where we cover topics such as developmental behavior, behavioral modification, and clicker “teaching”! These will provide more detail on individual concepts and how to apply these when interacting with your residents!

Infographic

Looking for an easy way to share information on how animals learn? Check out our infographic!

How Animals Learn Infographic by Amber D Barnes

SOURCES:

Habituation vs. Learned Helplessness in Horses | The Horse

Rapid Reversal Of Fear And Behavior Aggression In Dogs And Cats | Dr Sophia Yin

Behavior Modification In Dogs | The Merck Veterinary Manual

Learned Behavior In Animals – Advanced | cK-12

Teaching, Learning, Assessment, Curriculum And Pedagogy | Stellanbosch University