Resource Acknowledgment

The following resource was written for The Open Sanctuary Project by guest contributor Josué Cabrera. Josué specializes in providing conflict support using the principles of transformative justice. He has worked with multiple organizations and activists within the animal liberationA social movement dedicated to the freeing of nonhuman animals from exploitation and harm caused by humans. movement and is passionate about building communities of care and accountability using a transformative justice framework.

This Resource Is Part Of A Series!

This resource is the second in a series addressing conflict support using transformative justice principles. For Part I, “Understanding Dominant Culture, How It Shapes Our Behaviors And Envisioning Alternatives,” please click here! Stay tuned for more resources on conflict support coming soon!

Introduction

Understanding how the dominant culture permeates our communities is the first step toward creating change. Now that we can name the problem, it’s time to build a solution. If you’re fortunate, your group’s structure may allow your feedback to be heard and solutions to emerge. However, more often than not, you may encounter resistance from people who benefit from the dominant culture, consciously or unconsciously. While you can call their attention to the issues, they will likely prioritize working on “improvements” (reforms) rather than on radical change in the organization’s culture. This resource provides tools that you can use with others in your team to help change the conditions that allow the dominant culture to be the norm without relying on change coming from people in positions of power.

What Is Dominant Culture? A Refresher!

The question of recognizing dominant culture is addressed in Part 1 of this series. However, as a quick reminder, let’s remember that humans are complex and full of contradictions; our activist identities don’t prevent us from replicating norms and behaviors that we have been conditioned to accept as “the way the world works.” This resource series refers to those norms and behaviors as the “dominant culture.” However, our mistakes and actions that have harmed others do not define who we are, but they give us clues about what internal work we need to do. This resource series is meant as a tool to help us identify and face the oppressor that lives within each of us so that we can avoid replicating the very harms we wish to mitigate.

It’s important to note that this resource is meant to help individuals cope with personal tensions, not to address abusive and/or harmful behavior or create structural change. The latter will be addressed in a future resource. The tools shared in this resource are meant for everyday interactions that can sometimes scale up to significant conflicts. Prevention is one of the best de-escalation tools. Therefore, in this guide, we will share strategies that can prepare you for brave conversations, help you communicate issues more effectively, and help you navigate the aftermath of these conversations. Additionally, we will provide some tools to help you build relationships that are grounded in trust, solidarity, and mutual support. You can also download our worksheet (also linked at the bottom of this resource) so you can work on using these tools together with your team!

Remember that transformative justice is not something you can do alone. Instead, it is something that emerges when you build the right relationships. While you can do some of this work by yourself, it won’t necessarily improve the culture of your team. Only by working collectively and normalizing new norms can you start practicing transformative justice as a group. It’s an uphill journey that takes time and will be challenging for everyone involved. However, let’s dare to sit through uncomfortable situations and come out on the other side stronger. We’re all in this together. Let’s start exploring this process by discussing some tools you can use for effective and authentic communication with your community members!

Tools For Communication

Effective communication and empathy are vital components of all healthy relationships and communities, primarily because they allow us to foster connection and understanding with one another. When conflict arises, it is essential that we develop these skills so we can properly recognize and empathize with both our own and others’ perspectives. In this section, we will explore the three-part process of practicing empathy for yourself, empathy for the other, and how to facilitate the emergence of new possibilities to meet everyone’s needs. By practicing these steps, we can build empathy and improve our ability to navigate conflicts with compassion and understanding. Let’s give you a little context to imagine this process in practice using a hypothetical!

Examples and Scenarios Described Really Are Hypothetical!

All hypothetical examples and scenarios offered in this resource are indeed hypothetical: they are not based on any “real-life situation.” Instead, they are crafted based on some of the many examples of conflicts that may arise in a sanctuary or rescue setting. They are meant for educational purposes only.

Imagine two colleagues who work together at a farmed animal sanctuaryAn animal sanctuary that primarily cares for rescued animals that were farmed by humans.. Tiara and Janis both work in bird care and share many similar values. However, Janis sometimes has a dark sense of humor and will make jokes that rub Tiara the wrong way. Specifically, Janis habitually refers to a particular flock of large breedDomesticated animal breeds that have been selectively bred by humans to grow as large as possible, as quickly as possible, to the detriment of their health. chickens as “the Poop Troop,” or “the Big Poopers.” The use of these words is uncomfortable to Tiara. She’s concerned about visitors overhearing them and about potentially reinforcing stigma or biases against these birds. She would like to talk to Janis about this but is afraid of jeopardizing their friendship and work relationship.

So what can Tiara do? Check out our three-step process below and how Tiara and Janis worked through them!

Part I: Empathy for Yourself

1. Observe and note what triggered your reaction and any judgments or stories you have about the other.

Example: Tiara doesn’t like using words that reinforce bias against farmed animalsA species or specific breed of animal that is raised by humans for the use of their bodies or what comes from their bodies., especially large breed chickens, of whom she is especially fond. She feels fearful of reinforcing bias against chickens as “dirty animals” and of reinforcing biases against large breed chickens in particular.

2. Identify the sensations and emotions in your body.

Example: Tiara feels anxiety and discomfort when she hears Janis’ jokes. It makes her feel tense and a bit short of breath. She feels a sinking sensation in her stomach and a tightness in her chest.

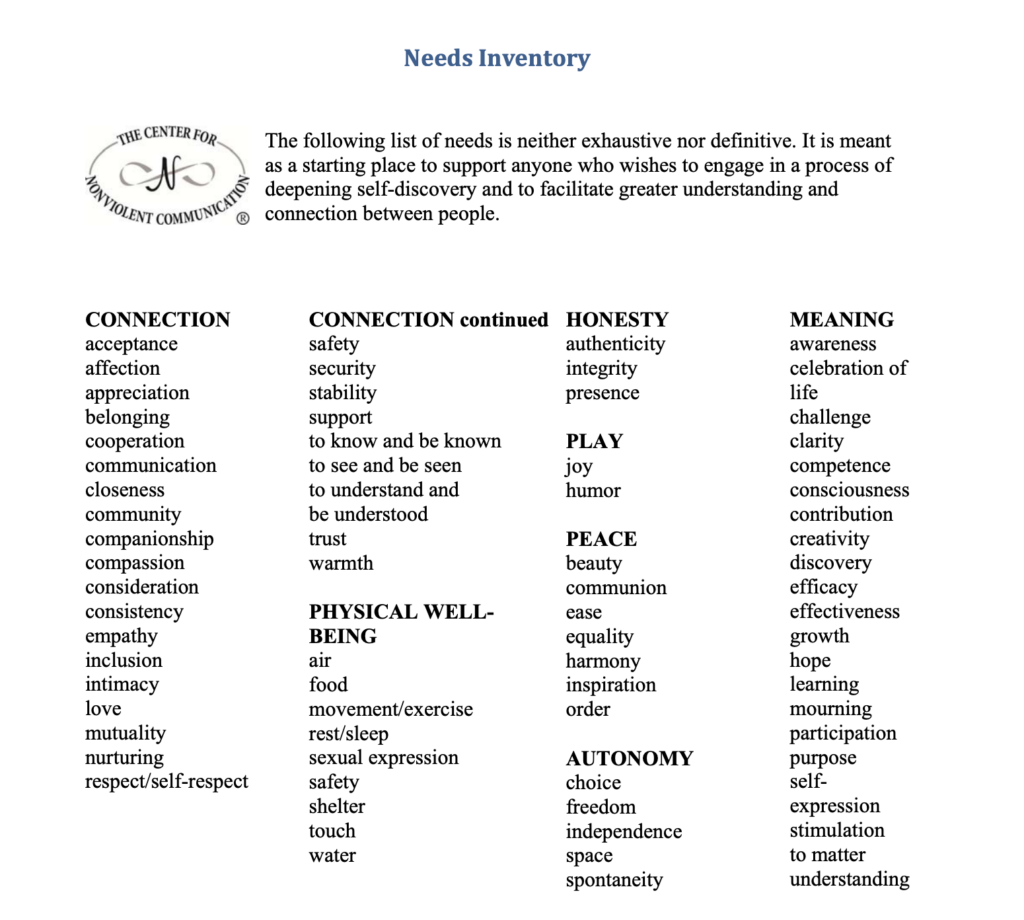

3. Connect with your universal human needs. What does this mean? Universal human needs are considerations we should all keep in mind when it comes to our feelings around conflict. Acknowledging these can help us maintain our boundaries, respect those of others, as well as foster a greater sense of empathy for each other! Check out the list below to get a better idea of what these needs might look like!

Email: cnvc@cnvc.org Phone: +1.505-244-4041

Example: Tiara feels a warm and close connection with Janis generally, but she also feels at times that Janis’ language use infringes on some of her basic needs for connection. Specifically, she thinks the language Janis uses is disrespectful to the animals and also makes her feel disrespected and unsafe, and that her need for security is infringed upon when she hears it.

4. Cycle through Steps 1 through 3 until you feel a sense of inner calm and centeredness.

Example: Tiara works through steps 1 through 3, and as she does so, she is better able to identify and narrow down her triggers. The larger scale anxiety she has felt over this issue becomes identifiable and more manageable to her. She understands better why Janis’ language use is stressful to her, and feels less generalized stress.

Now that we’ve outlined how you can work through some steps to foster empathy within yourself when you encounter a conflict, as well as an example, let’s consider how you can foster empathy for others who may be involved! Let’s revisit Tiara’s process in coping with her conflict with Janis’ language use, as she considers how to empathize with others.

Part II: Empathy for Other

- Observe and note what you said or did that might have triggered the other person, as well as their thoughts about the situation.

Example: Tiara remembers that when she talked to Janis about this flock before, she joked about how “chonky” they are. She also remembers noting that while she mentioned once that she didn’t like Janis’ use of certain language, Janis joked back that the use of this kind of “jokey” language was just part of how she expressed affection for those she cares about.

- Identify the sensations and emotions the other person may be experiencing.

Example: Tiara considers that Janis might well be surprised to learn that her casual but repeated use of this kind of language might be hard for her and others, and that she might feel defensive or afraid of punishment as a function of her objection to it. She remembers that Janis has told her stories about how in her close relationships, her friends use words that might be considered insulting as terms of endearment.

- Connect with the other person’s universal human desires or needs.

Example: Tiara remembers that she and Janis both work side by side under a hierarchical structure, and that their friendship and daily mutual support of each other are really important! They look forward to seeing each other each day, and always enjoy fun banter and working with the animals under their care together. She knows that Janis values her as a friend too, and that their relationship makes their day-to-day work more fun and positive.

- Cycle through steps 1-3 until you feel more connected to the other person and non-reactive.

Example: Tiara works through steps 1 through 3 and though she’s still not comfortable with accepting Janis’ language use, she now feels better prepared to communicate the impact it is having on her without running the risk of blaming or shaming her for her actions.

Part III: The Emergence of New Possibilities to Meet Your Needs

1. Reflect on any new insights or ideas that have emerged from practicing Parts I and II.

Example: After reflection, Tiara recognizes that she might need some support in coping with this in a thoughtful way. She recognizes she needs to reach out to a trusted friend to help her work through this! Luckily Tiara has already formed a “pod” to help support her!”

What’s A Pod?

You will note that throughout our running examples here, we mention “pods.” While for now we’re focusing on tools individuals can use to do internal work as they cope with interpersonal conflict, we will discuss pods later in this resource and how you can use them to build a mutually supportive and accountable community within your organization!

2. Develop a specific action plan to meet your needs.

Example: Tiara has a clear vision of the situation now and decides to ask Hannah, a fellow member of her “pod” to help her practice what she wants to communicate to Janis. This will help her feel more comfortable when taking the brave step of offering feedback to Janis.

3. Practice your plan through role-playing or journaling.

Example: Tiara and Hannah switch roles back and forth, with Tiara communicating feedback and Hannah receiving it, and vice versa. This helps Tiara further practice empathy for herself, and for Janis!

4. Cycle through all three parts as needed to continue building empathy. As you attempt to empathize with the other person, you may get triggered into more of your own reactions. If this happens, go back to Part I and cycle back and forth between Part I and Part II as needed.

Example: As Tiara and Hannah keep working together to practice this conversation, Tiara recognizes more and more that she has a fundamental aversion to conflict based on some childhood experiences that have caused some of her anxiety around this. Her childhood made her fearful and sensitive about the prospect of punishment. For Tiara, practicing this conversation helps to ease this anxiety.

Safety Planning

If you find yourself in a situation where you feel unsafe and triggered, it’s important to have a safety plan in place. Safety planning involves identifying potential risks and mapping out resources to minimize those risks. It’s not just about physical safety, but also psychological, moral, and social safety. To create a safety plan, start by identifying how your body feels when certain emotions arise, and then recognizing what triggers those emotions. From there, you can develop detours, or coping mechanisms, to use in tense situations. It’s best to work on creating a safety plan with others, such as your pod, a group of trusted individuals who can support each other in the process. Again, we’ll talk more about pods, how you form them, and how they can support you later on in this resource, but for now, let’s talk about some tools you can use for sharing feedback in a supportive and helpful way!

Tools For Giving Feedback

Giving feedback can be a challenging task, but it’s an essential part of building healthy relationships and addressing conflict. After building empathy and identifying your needs, you are now ready to give feedback to the other person. The following steps can guide you through the process:

1. Ask for consent before you talk and share the topic of the feedback. Respect the other person’s boundaries and make sure they are willing to receive the feedback.

Example: Tiara approaches Janis and says, “Hey Janis, I was wondering if I could talk to you about the impact of the language you use when referring to some of the birds we care for. It doesn’t have to be now, if you’re feeling stressed or overwhelmed, but I would appreciate it if you’re open to having a conversation about it.”

A Quick Introduction To Consent

The “legal” definition of consent is when a person who has capacity (or the ability to make a decision) voluntarily and willfully agrees to the proposition of another person, in the absence of coercion, fraud, or error. Keep in mind that in high pressure environments, many factors can influence an individual’s capacity to consent to a proposition. These can include power dynamics, stressful circumstances, or other factors. When asking for consent, it can be helpful to make sure to affirm with the other party that they feel that they have the capacity to make a decision about engaging into an interaction. Note that in the above example, Tiara gave Janis the opportunity to take space to have the interaction in another context, if that is more comfortable for her.

2. Offer appreciation and/or care early on if it feels authentic. It’s important to show that you trust the other person to be self-accountable rather than threatening to hold them accountable.

Example: “Thank you for your interest in what I want to share with you. Your willingness to talk about it makes me feel very comfortable.”

3. Use Non-Violent Communication (NVC) to make a request in an assertive but not aggressive way. This format includes four components:

-What you observed;

-How you felt;

-Why it matters to you;

-And what your request or wish is.

Speak from your experience using ‘I’ sentences. This approach helps you to focus on your experience without blaming or accusing the other person.

Example: Once Janis has consented to the conversation and accepted Tiara’s appreciation, Tiara says to Janis, “I noticed that you often refer to some of the birds we care for as “the Poop Troop,” or “the Big Poopers”. When I hear you use that language toward them I feel anxious and uncomfortable. I think it reinforces the stigma that they are dirty animals. I worry visitors may hear you and then leave with that impression of chickens in general. Would you mind not referring to them in these ways?”

4. Take responsibility for your own needs in the situation and your emotional baggage. It’s important to communicate how their actions impacted you and what you need to feel better.

Example: Tiara explains to Janis, “Now that I’ve recognized the impact that that language has on me I’ve been exploring new tools for processing those emotions in a constructive way. I think if we can agree to not use those terms to refer to these birds, it would not only avoid reinforcing bird stigmas to others, but it will also help me avoid feeling emotionally activated when working together.”

5. Don’t assume you know what happened for the other person or what they thought or felt. Separate observation from judgment and evaluation. This will help you avoid misunderstanding and build a shared understanding of the situation.

Example: Instead of saying, “I know you’re just grossed out by poop,” Tiara offers space for Janis to share her own feelings about the situation.

Tools For Receiving Feedback

It’s important to recognize that not only will you encounter situations in which you will want to offer feedback, you may also find yourself in a situation where you may receive it! Practicing some of the tips below can help you become a more willing and able recipient, and make those interactions more productive and mutually beneficial!

1. When asked for consent, consider if you are ready to listen. If you’re unsure, ask about the topic and whether it’s constructive or appreciative. Then decide on an appropriate time for you to receive the feedback.

Example: When Janis is approached by Tiara, it’s important that she consider carefully how she is feeling in this moment. For example, if she’s feeling very overwhelmed by a long task list, or is overtired at the end of a long day, she might want to ask if this is a conversation that they can have in a time and space where she feels she has more capacity to listen.

2. Try to stay grounded and emotionally neutral. Remember to breathe and be present in the moment.

Example: Janis, like many people, feels fear around receiving feedback. It feels to her like a prerequisite to punishment, and so she reminds herself that Tiara is her friend and colleague. She reminds herself that feedback does not necessarily equate to punishment, and that it is important not to jump ahead to that conclusion. She takes some deep breaths and clears her mind so she can listen to Tiara without bias.

3. You may be triggered by what is said and enter a defensive mode. Remember your safety plan and take a break if needed. Just listen and try to learn rather than defend or deny the feedback. Relax into yourself and receive it as information rather than confirmation that something is wrong with you.

Example: Even though Janis has taken the steps above, she is somewhat irritated by Tiara’s feedback at first. After all, Janis was just joking around and made it clear that the jokes she was making were grounded in affection! As she listens to Tiara, however, she can see her perspective better. She recognizes Tiara is making a good point with regards to visitors who might hear and take her jokey comments in a way she did not intend. She also hears that Tiara is not accusing her of “being a bad person,” but instead that Tiara has her own feelings about the language used, and that this is part of what made these interactions hard for her.

4. Ask questions to make sure you understand the feedback and the other person’s perspective.

Example: Janis asks, “Is it just comments about the “Poop Troop” that upset you, or are there other things I say that upset you? Is using terms that might be considered “insults” as terms of endearment upsetting to you generally? Or is it just this specific time?”

5. Listen empathically for the feelings and needs underlying what is being said to you, especially if it’s hard to hear.

Example: Janis listens carefully to what Tiara is sharing with her and recognizes that even though her intention was never to make anyone uncomfortable, the impact of the language she was using was nonetheless negative. She feels sorry for the situation and appreciates Tiara for bringing her attention to it. The trust required to share the situation and the care with it was shared made her feel comfortable in making the necessary changes. She now reaches out to people in her own pod to debrief the situation and dive deeper into how she feels. Ultimately, in spite of her temporary discomfort, this leads to her celebrating the strong relationships she has with Tiara and the rest of her coworkers.

Giving and receiving feedback is an essential skill for building healthy relationships, fostering growth, and addressing conflict. To do this effectively, it’s important to prepare by building empathy, identifying your needs, and creating a plan to meet those needs. When giving feedback, it’s crucial to approach every situation with care, speak from your own experience, and take responsibility for your own needs and emotions. When receiving feedback, it’s important to remain grounded, listen empathically, ask questions for clarification, and take responsibility for your emotions. By using these steps and tools, we can build stronger connections, improve our communication skills, and create a more positive and productive environment.

After Giving Or Receiving Feedback, It’s Important To Check In On How Everyone Is Feeling!

Ask the other person how they’re feeling after receiving the feedback, or take a moment to reflect on how you feel if you were on the receiving end of it. If requests were made during the feedback process, it’s important to create a plan to fulfill those requests. Start by checking your capacity to meet the requests and break them down into actionable steps that you can take. This will help to make the requests more manageable and achievable. Make sure to measure progress along the way to ensure that you’re on track to meet the requests.

If both parties are willing, set a date for a follow-up conversation to check in on the progress. This can help ensure the requests are being met and the feedback has been effective in addressing the issue at hand. Remember, giving and receiving feedback is an ongoing process that requires open communication, empathy, and a willingness to make changes. By following these steps and continuing to work on building healthy relationships, you can create an ever-evolving and successful culture that is grounded in trust, solidarity, and mutual support.

Tools For Community Building: Pods And Pod Mapping

The process of unlearning what the dominant culture taught us and adopting alternatives can be a challenging and sometimes isolating process, but it doesn’t have to be. As Mariame Kaba has wisely said, “Everything worthwhile is done with other people.” Having the support of others who share your goals and values can make the process easier, more impactful, and even enjoyable. However, the term “community” can mean different things to different people. In this resource, we utilize the term community to mean a group of people who share a sense of connection and interdependence, and behave as a collective group rather than just a loose association of individuals.

Building community can be done in various ways, but we’d like to share one approach (mentioned above) that is particularly useful in promoting cultural transformation. This approach doesn’t rely on organizational support, though it would certainly benefit from it. Instead, this approach is based on the organic emergence of individuals coming together to support one another. In the forthcoming resources in this series, we will share steps that can be taken at an organizational level, but for now, we’ll explore practical steps for creating and nurturing supportive communities, starting with the concept of “pods”.

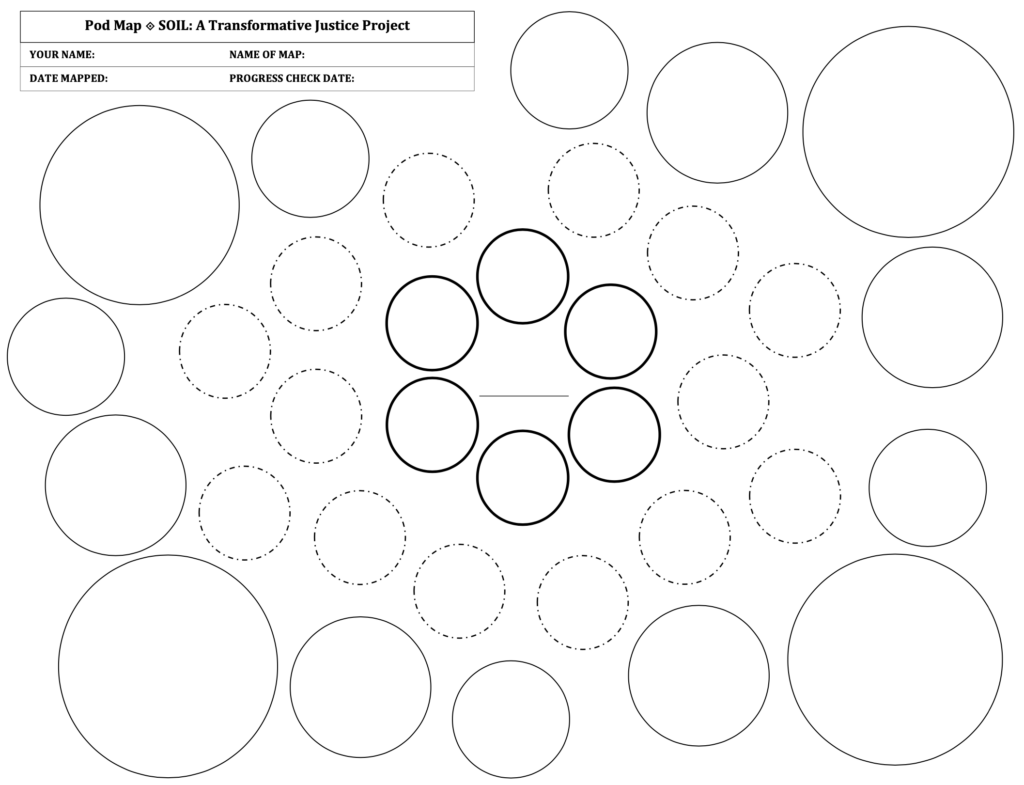

The Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective (BATJC) identified the importance of having a group of people to call on for support when faced with harmThe infliction of mental, emotional, and/or physical pain, suffering, or loss. Harm can occur intentionally or unintentionally and directly or indirectly. Someone can intentionally cause direct harm (e.g., punitively cutting a sheep's skin while shearing them) or unintentionally cause direct harm (e.g., your hand slips while shearing a sheep, causing an accidental wound on their skin). Likewise, someone can intentionally cause indirect harm (e.g., selling socks made from a sanctuary resident's wool and encouraging folks who purchase them to buy more products made from the wool of farmed sheep) or unintentionally cause indirect harm (e.g., selling socks made from a sanctuary resident's wool, which inadvertently perpetuates the idea that it is ok to commodify sheep for their wool)., abuse, or even challenging accountability processes. They named this type of relationship a “pod.” This same approach can be used to navigate conflict, even when the impact is not necessarily described as acute harm. Building relationships that are based on supporting one another when mistakes occur, when we are faced with a challenging situation, or when we’ve received feedback that makes us question our capacity to contribute to the team. You can have multiple pods – some for general support and others for specific situations. Your pods can help you prepare for brave conversations, normalize new ways of communicating, prepare and practice your safety plan, and practice accountability when it’s necessary.

In this way, we can build supportive relationships that sustain us in times of difficulty, allowing us to better support ourselves and others. Here are some steps based on the approach developed by BATJC that can help you create your own pods.

Building Pods: Steps for Creating Supportive Relationships

- Identify people you trust. Think about the people in your life who you trust and feel comfortable talking to about difficult situations or emotions. This could be a small group of friends, family members, colleagues, or community members.

- Reach out and explain your intentions. Once you have identified potential pod members, reach out to them and explain your intention to create a supportive community for navigating conflict, harm, or challenging situations. Be clear about the purpose of the pod and the type of support you are looking for.

- Obtain consent. Ask for their consent to be part of the pod and to provide support as needed. Make sure everyone is on the same page and has a clear understanding of what it means to be part of the pod.

- Identify additional pod members. If you feel like you need more people in your pod or if there are people you would like to build a stronger relationship with, reach out to them and ask if they would be interested in joining.

- Establish communication and expectations. Once you have your pod members, establish clear communication channels and expectations. This could include regular check-ins, setting boundaries and agreements, and identifying ways to support each other.

- Identify available resources. Identify resources that can support you and your pod members, such as therapists, HR professionals, community groups, and educational materials. Make sure everyone is aware of these resources and knows how to access them.

- Regularly check in and evaluate. Regularly check in with your pod members and evaluate how the pod is working. This could include discussing successes, challenges, and ways to improve.

Creating a pod can take time and effort, but it is an important step in building a supportive community. By intentionally creating relationships based on trust and mutual support, you can navigate difficult situations with more confidence and resilience. Check out this worksheet series created by Mia Mingus.

Example: In the scenario presented earlier, Tiara and Janis both benefitted from having people with whom they could explore their emotions and prepare for brave conversations together. Prevention is the best de-escalation. Taking the time to build these networks of support and normalizing communication methods that come from a sense of care for yourself and people around you, make it easier to transform tense situations into opportunities of growth and deeper bonding.

Conclusion

When thinking about tools for navigating conflict it is understandable to look for easy, step-by-step solutions that we can apply during those situations and although that approach can be useful in the short-term, if we aim to transform our culture around conflict and build stronger communities, a more radical approach is the way to go. Starting by intentionally building pods, practicing tools for better communication and normalizing them even in the smallest situations will prepare us for the bigger challenges that come with group work. What we shared in this resource can help you and your group get started moving from the ground up towards a culture that challenges the dynamics of dominance, supremacy, and competition that the current dominant culture impose on us. Stay tuned for our next resource, in which we will highlight the most common sources of conflict that groups face, what group norms and structures can help us address them, and how a culture of self-accountability can look when major conflict happens.

Download The Workbook

We’ve put together a workbook that your group can use as an exercise in thinking about your communication and community building! Enter either your organization’s name or your name and email below to download the workbook!

We promise not to use your email for any marketing purposes! Need to access this workbook in a different way? Contact us!

SOURCES

Safety Planning For Conflict | Transforming Culture

Nonviolent Communication Instruction Self-Guide | The Center For Nonviolent Communication

Consent Is Accountability | Barnard Center For Research On Women

Everything Worthwhile Is Done With Other People: Mariame Kaba | ADI Magazine

Tools For Navigating The System | Bay Area Transformative Justice Collective

Turning Towards Each Other: A Conflict Workbook | Weyam Ghadbian, Jovida Ross

Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During This Crisis (And The Next) | Dean Spade

Pods: The Building Blocks of Transformative Justice & Collective Care | Mia Mingus