Regardless of where your sanctuary is located, flies will likely be an issue for cowWhile "cow" can be defined to refer exclusively to female cattle, at The Open Sanctuary Project we refer to domesticated cattle of all ages and sexes as "cows." residents during certain seasons. While some fly species may simply agitate or annoy cowsWhile "cows" can be defined to refer exclusively to female cattle, at The Open Sanctuary Project we refer to domesticated cattle of all ages and sexes as "cows.", others can spread disease or cause other health challenges, and some species will lay eggs in wounds, leading to flystrike. Proper fly mitigation strategies are imperative to keep cow residents both comfortable and safe, but figuring out what is best for your sanctuary and your residents can raise ethical questions regarding the overall impact on the environment and other living beings in the surrounding area.

While you will never completely prevent flies from living at your sanctuary, you can take certain steps to prevent large fly populations from developing and to reduce the chances of flies having a negative impact on your residents. In some cases, with proper procedures, you may be able to prevent certain potential health challenges all together. Fly mitigation plans require multiple strategies working in unison, and some strategies may need to be changed over time to prevent issues with resistance. We suggest working with your local cooperative extension for more information about the common fly species in your region, possible preventative measures, and the impact these measures will have on the environment and other living beings, including other resident species. Just be aware that they may recommend strategies that are not appropriate at a farmed animal sanctuaryAn animal sanctuary that primarily cares for rescued animals that were farmed by humans., such as the use of insecticide impregnated ear tags.

While there are a variety of strategies a sanctuary may choose to employ, it is imperative that you also focus on finding ways to make the sanctuary, and specifically your residents’ living spaces, less welcoming to flies. Start by identifying areas that attract flies to feed or lay eggs, and eliminate these areas whenever possible. For those that cannot be eliminated, see if there is a way to move them away from resident living spaces. Many species lay eggs in or near poop or decaying organic matter, so finding ways to keep these to a minimum can make a big difference. Without this being part of your overall strategy, you will likely either find that the practices listed below are not effective or may find that you have to rely more heavily on environmentally harmful insecticides. The following practices can help manage fly populations:

- Regular Cleaning Of Living Spaces– Cow poop, soiled bedding, and old hay, straw, or grain are often used as breeding areas for flies, so keeping spaces clean is imperative when it comes to fly mitigation. Indoor living spaces should be cleaned frequently, and soiled bedding and old food should be removed. It can be difficult to clean entire outdoor spaces, especially if cow residents have access to a large, lush pasture, but poop in outdoor spaces that is in close proximity to indoor spaces should be removed regularly, especially waste in areas without vegetation. To make poop out in the pasture less welcoming to flies, you can manually break it up, which will cause it to dry out more quickly. Depending on your set-up, this may be done with a rake or pitchfork, by using equipment such as a tractor and drag harrowA tool which breaks apart clumps of waste, soil, or plant life by being dragged through areas, particularly pastures., or if you are lucky enough to share your property with dung beetles, they will be a great help in this endeavor.

- Manure Management– In addition to just removing poop from living spaces, you also need to have a plan to manage the large amounts of poop your residents will produce. For more information on manure management, check out our introductory and advanced resources on this topic.

- Be Strategic With Compost Piles– Since flies seek out decaying organic matter, compost piles can be a hotspot for flies. Keeping these areas away from resident living spaces can help keep the flies away, too. For more information on composting, check out our resource here.

- Address Drainage Issues– Wet, swampy areas can also be popular breeding areas for certain types of flies. Your cow residents will likely enjoy having access to natural water sources such as ponds or streams, and the benefit they bring to your residents likely outweigh the role they may play in fly issues, but if there are drainage issues on your property that result in standing water or swampy areas, it’s helpful to work to address these.

Unfortunately, when it comes to caring for cows, it seems like even with the best cleaning protocols, you will still have significant fly populations and will need to have additional strategies to help protect your residents from painful bites and possible disease spread. Which strategies you ultimately decide to use will depend a lot on which types of flies are most prevalent in your region and will also depend on your sanctuary’s Philosophy of Care. It’s always important to really think through the potential impact of any practice you enact at your sanctuary. When it comes to fly mitigation, it can be a delicate balancing act of ensuring your residents’ needs are being met and that you are responsibly protecting them from potential harmThe infliction of mental, emotional, and/or physical pain, suffering, or loss. Harm can occur intentionally or unintentionally and directly or indirectly. Someone can intentionally cause direct harm (e.g., punitively cutting a sheep's skin while shearing them) or unintentionally cause direct harm (e.g., your hand slips while shearing a sheep, causing an accidental wound on their skin). Likewise, someone can intentionally cause indirect harm (e.g., selling socks made from a sanctuary resident's wool and encouraging folks who purchase them to buy more products made from the wool of farmed sheep) or unintentionally cause indirect harm (e.g., selling socks made from a sanctuary resident's wool, which inadvertently perpetuates the idea that it is ok to commodify sheep for their wool)., while also considering the bigger impact on the environment and other living beings who may not be official residents, but still call your sanctuary home.

Fly Mitigation Practices To Consider

In most cases, you will need to employ multiple strategies to mitigate flies at your sanctuary. And while this resource focuses on cow residents who often have some of the biggest issues with flies, keep in mind that you must also have sanctuary-wide practices. Focusing on fly mitigation in cow resident areas, but not in other spaces will not be nearly as effective as having a more holistic approach. However, with the amount of poop they produce, your cow residents will be very popular with flies and will require special attention. Also keep in mind that certain practices discussed below may not be compatible with each other, or will require careful implementation when used together. It’s important to come up with a cohesive plan consisting of practices that work well together, so be sure to evaluate your plan as a whole, and make sure you are not using practices that may be reducing the efficacy of other practices you employ.

When evaluating a particular fly mitigation strategy, be sure to consider which species the practice targets. Looking at specific species populations, rather than lumping all fly species into one massive population, is imperative when evaluating efficacy. Judging a practice aimed at controlling one species of fly as a failure based on the presence of a different species could result in abandoning practices that were actually working! Additionally, it’s important to contextualize population sizes. For example, if you have been dealing with horn fly issues, having hundreds, rather than thousands of horn flies on a resident may be the goal.

Below we will discuss some of the practices that are commonly used at sanctuaries caring for cows, which includes topical treatments, biological control, dietary fly control treatments, and fly masks.

Topical Fly Mitigation Strategies

Conventional Topical Insecticides

Be Sure To Consider The Implications Of Insecticide Use

While many people have concerns about the impacts of insecticide use, it seems many sanctuaries find it impossible to manage fly populations without at least some insecticide use. We recommend employing other strategies as well, and when using insecticides, use judiciously.

During the fly season, many sanctuaries routinely treat their cow residents with commercial topical insecticides designed for use in cows. Unlike fly repellents, these products kill flies (and depending on the type, may kill other invertebrates and aquatic life) who come into contact with the product. It’s imperative that you read all package instructions and make sure you are using the product in a way that will result in the least amount of harm to the ecosystem. It may seem unconscionable to some sanctuaries to intentionally destroy life to protect other life, but the risks certain fly populations pose to residents are severe. Insecticides may be a pour-on formulation or a topical spray or powder applied at regular intervals based on the manufacturer’s recommendation. Pour-on formulations are often preferable because they require less frequent application- typically no more than every two weeks- and only require a small amount of the solution to be applied down the resident’s back. Other insecticide formulas may be intended for use daily, every few days, or weekly, and may require more thorough distribution of the product (which can be difficult if residents are not fans of the treatment).

While the use of cow-safe topical insecticides can be effective at managing certain fly populations, they can become less effective over time if the flies develop a resistance to the treatment. We suggest consulting with an expert in your region in order to determine the best practices to prevent resistance issues and to prevent overuse. While pour-on ivermectin is often used to help control certain fly species, this must be used strategically; ivermectin also treats internal parasites and frequent use could contribute to resistance of internal parasites, which is already a growing issue.

“Natural” Fly Sprays

If the idea of regularly using insecticides concerns you (and rightfully so), you could try using or making a fly spray that is made of less toxic ingredients. While some essential oils and plant extracts can act as deterrents or repellents, others are toxic to flies but are believed to have less negative environmental impacts than conventional insecticides. There will be times when you must use harsher treatments (such as if cows require treatment for specific parasitic infestations or if other management strategies are not working), but you might find more eco-friendly alternatives that can be used in place of, or in addition to, conventional treatments.

One challenge with botanical fly sprays is that they typically require application multiple times each day, which may not be feasible depending on your resident population and staff or volunteer capacity (not to mention that some residents may not be fans of being sprayed, so attempting to spray them multiple times each day might be nearly impossible). Unlike pour-on insecticides that require application of a small amount of solution down the back every few weeks, botanical fly sprays typically must be applied to an individual’s entire body in order to be effective. There are some commercial botanical blends marketed for cows, and there are also numerous recipes for Do-It-Yourself concoctions. Be sure any formulation you use is free of any ingredients that are toxic to cows, as they will likely ingest some of the treatment while grooming, and keep in mind that just because something is plant-based or labeled as “natural”, doesn’t mean it is entirely safe.

Some sanctuaries use botanical blends daily, and while they may still use conventional insecticides, they may not need to rely quite so heavily on them. For example, you might use a pour-on insecticide every few weeks, but in between treatments, opt to use a botanical formula rather than a conventional insecticide meant for frequent use, thus cutting down on the overall amount of insecticides used.

There is some research available regarding certain plant extracts and essential oils acting as repellents or insecticides against certain fly species. When available, we share specific options in the common fly species sections below. Be aware that there may not be information available about the long term impact these substances have on cows, so we recommend you have a discussion with your veterinarian or other expert before implementing these treatments at your sanctuary. Also keep in mind that cows may avoid certain strong odors such as citronella, which could make applying these treatments more difficult.

Self-Treatment Devices

In addition to topical treatments that are applied directly on each resident, the use of self-treatment devices such as the Cow Buddy, cow rubs, and dust bags can also help protect cows. These devices can be used in conjunction with cow-safe insecticides, and may also be able to be used with botanical formulas. By strategically placing these devices in areas where the cows must frequently pass through (also called “forced-use”), these devices will regularly apply treatments to a cow’s face, back, or sides. In herds consisting of individuals of varying heights, some products may be difficult to position at a height at which everyone will benefit.

Opt For Mineral Oil

While the use of diesel or heating oil in these devices is a common recommendation, we strongly advise against this practice. Cows can develop “petroleum product poisoning” from exposure to petroleum, gasoline, diesel, kerosene, crude oil, and other petroleum-based products. When creating a mixture for use in a rub or rope system, we recommend using mineral oil instead.

Make sure you keep these devices regularly filled (or charged) to ensure their effectiveness. Most are designed for use with conventional insecticides, but you may be able to use botanical blends instead. Watch closely when using solutions with strong scents, as cow residents may avoid using the device if they do not like the smell.

Scent Preferences

Cows are much more sensitive to smells than humans and just like us will have certain scents they enjoy more than others. One study revealed that when given the choice between a device that released a lavender scent and a device that was not scented, cows chose the lavender. You might consider setting up your own informal experiment to see what cow-safe scents your residents seem to prefer, starting with a more mellow scent such as vanilla, and then adding their preferred scent in safe dilutions to self-treatment devices.

Biological Control Strategies

Parasitic Wasps

Some sanctuaries choose to use parasitic wasps, such as Fly Predators (which consist of multiple species of parasitic wasps). These are small pupal parasitoids that attack the pupae of some of the common flies that affect cows. This includes the common house fly, horn fly, biting stable fly, and lesser house fly. Parasitic wasps do not bite or sting and do not become an issue for cows or humans. They are typically ordered online, and their pupae are shipped in the mail on a set schedule during the fly season. If you choose to use parasitic wasps, be sure to work closely with the supplier to determine the best way to implement the system as the specifics of your sanctuary, region, and your resident population will need to be considered when determining a plan.

Ethical Considerations

While some sanctuaries have had good success with parasitic wasps, the decision to use them will depend on your sanctuary’s Philosophy of Care. Some sanctuaries may decide not to use them due to the ethical implications associated with buying living beings and having them shipped in the mail, while others may feel that more harm is done by using insecticides and are able to use fewer insecticides by purchasing parasitic wasps.

If you choose to use parasitic wasps for fly control, be aware that some fly mitigation strategies, such as some insecticides and premise fly sprays, can negatively impact parasitic wasp species more than the fly population you are trying to manage. Your cooperative extension service should be able to make recommendations regarding fly mitigation strategies that do not negatively impact parasitic wasp populations.

If you are interested in incorporating parasitic wasps into your mitigation strategies, but have ethical concerns about buying and shipping them, you can talk to your local cooperative extension about which species are common in your region and if there are things you can do to help protect these populations and encourage their growth. It seems that in most cases, naturally occurring populations may not exist in large enough populations or at the right times of year to make a noticeable difference in fly populations, but every region will be different.

Dung Beetles

Dung beetles exist on every continent except Antarctica and are classified by three types: “dwellers”, “tunnelers”, and “rollers”. While we often picture rollers when thinking about dung beetles, this type only accounts for 10% of dung beetle species. Each type of dung beetle helps with manure management in their own way. Dung beetles eat and bury large quantities of poop each day; in fact, they can bury poop that is 250 times their weight in a single night! In addition to eating poop, some species also eat fly larvae found in poop, thereby helping control populations both directly and indirectly. While doing what they do, they also break up a fly’s life cycle by burying fly eggs or larva and leaving less poop available for flies to lay eggs in. They can also break up the life cycle of some internal parasites as well. Rollers actually excrete a substance on the poop that repels flies, preventing them from laying eggs in it. According to Dung Beetles And Their Role In Nature, dung beetles can cause up to a 95% reduction in horn fly populations. In addition to helping to manage poop and fly populations, dung beetles improve the soil by aerating it and making it easier for water to penetrate it.

If you are interested in finding ways to increase local dung beetle populations, we suggest you contact your local cooperative extension. It will be important to identify which species are native to your region and what you can do (and what you should stop doing) to help increase their populations. This is not a quick fix- it could take quite some time for established populations to reach numbers where their impact is obvious. Dewormers and some insecticides and “feed-through” products used to manage fly populations can negatively impact dung beetle larvae. You will need to evaluate your overall fly mitigation strategy to find ways to promote an environment for dung beetles to thrive and to protect the current population. Avoiding the use of dewormers during times of the year when dung beetles are active, instead administering them when dung beetles are dormant, will help protect dung beetles from negative impacts, but of course this may not always be possible. You will also need to consider how your current practices may be adversely affecting local dung beetle populations, and how you can responsibly balance your residents’ current needs regarding fly control with practices that can attract and protect dung beetles.

Dietary Fly Control Strategies

“Feed-Through” Products

These products are intended to be fed to cows, but do not actually treat the cow or prevent adult flies from biting them. Instead, they pass through the cow and treat their poop (hence the name “feed-through”). These products either contain an insect growth regulator (IGR) or a larvicide. Both products work to control fly populations by preventing larvae from maturing into adults, but they work in slightly different ways. Some products target only particular species, typically horn flies, and therefore claim to have less negative impact on the ecosystem, while others have a broader impact. Be sure to thoroughly research products before you use them- especially if you are working to bolster dung beetle or parasitic wasp populations. ClariFly, for example, advertises that it will not affect parasitic wasps or adult dung beetles, but could harm dung beetle larvae.

In order to be effective, these products must be used according to manufacturer’s instructions. Most types recommend you start feeding them to cows 30 days before fly season starts, and continue using them until 30 days after the first frost. Sanctuaries who use feed-through products often opt for mineral formulation containing larvicides or IGRs (versus pelleted foods containing larvicides or IGRs or slow-release boluses, which are also available). It’s important to watch to make sure residents are eating the necessary amount, or the product will not be effective.

“Natural” Supplements

There are some supplements consisting of ingredients such as garlic, brewers yeast, and diatomaceous earth that claim to repel biting flies while also helping to prevent larvae in poop from maturing into adult flies. Bug Check Fly Control Supplement is labeled for use in cows, horses, alpacas, sheep, and goats, but is expensive and may not be a viable option for everyone. There seem to be more products available for horses, so you could consult with your veterinarian to see if any equine products may be appropriate for use with your cow residents.

Fly Masks

Some sanctuaries choose to use fly masks to help protect residents from face flies. These masks cover a resident’s eyes (and depending on the style, may also cover most of their face) and are made of a mesh material that allows individuals to see through the mask. If you choose to use fly masks, be sure to consider that some residents may be very adverse to them. While there are certain things you can do to help a resident feel more comfortable with the idea of wearing a face mask, keep in mind that they may not be a good option for everyone. It’s a good idea to start familiarizing residents with fly masks well before you actually need to start using them. It can be helpful to make the fly mask a part of a routine so that they are used to seeing, smelling, and feeling it. Using positive reinforcement can be very beneficial, as can letting them spend some time smelling the mask (maybe with some calming lavender scent!), or rubbing the mask against them just as you would with your hand when you petAn animal who spends regular time with humans in their home and life for companionship or human pleasure. Typically a small subset of animal species are considered to be pets by the general public. them. When residents first start wearing them, it can be a good idea to start by only having it on for short periods of time and then increasing the amount of time they wear it as their comfort increases. It’s best not to force or rush things unless medically dire. Residents who are comfortable wearing the mask can wear it for most of the day, but it’s always a good idea to watch closely for any signs of discomfort or irritation.

Depending on the style of mask, you may be surprised how difficult it can be to identify individuals who are wearing a mask, especially if you care for many residents of the same breed with similar coloring, so you may want to add names to masks or add some other identifier.

Protect Wounds From Fly Strike

In addition to having an overall fly mitigation plan, it’s important to take extra precautions if residents have a health issue that could attract flies. Some species will lay eggs in open wounds, so you’ll want to offer residents an additional layer of protection. Keeping wounds cleaned and covered or using an animal-safe fly repellent ointment around the affected area can be helpful. Be sure to closely monitor wounds for signs of fly strike (the presence of maggots in wounds) so that in the event it happens, you are able to address it as soon as possible.

Common Fly Species That Can Affect Cows

In addition to agitating cows by swarming around their faces or biting them, some species can also spread diseases, and not just within your sanctuary herd; depending on the species and how far they travel, they can also spread disease from nearby agricultural operations. You can work with your local cooperative extension service for more information about the common fly species in your particular region- knowing which flies will be of concern will help guide your mitigation strategy.

Common fly species that affect cows include:

Face Flies (Musca autumnalis)

These flies resemble house flies, but are slightly bigger (6-8mm) and darker in color. As their name suggests, they cluster on a cow’s face, especially around their eyes and nose. These flies do not bite cows, but in addition to eating nectar, females will feed on secretions from a cow’s eyes and nose, which is why they congregate in these areas. They also feed on vaginal and wound secretions. Face flies can damage the conjunctiva while feeding, resulting in runny eyes. This damage can also create a point of entry for the bacterium Moraxella bovis, which causes Pinkeye. In addition to spreading Pinkeye, face flies can be vectors for other diseases including infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR).

Each face fly only spends approximately 5-10 minutes feeding on these secretions each day, spending the majority of the day off of the cow, which can make control difficult. There are “feed-through” products available to control face flies, but because face flies can travel from nearby cow herds, these may not be effective. Face flies lay eggs in fresh poop out in pastures, so strategies that break up or remove poop from pastures can be helpful, but like “feed-through” products, will not address adult face flies traveling from other areas. The use of cow rubs or dust bags can be helpful as long as they are positioned to make contact with a cow’s face. Some sanctuaries regularly apply a permethrin solution to their cow residents’ faces to help deter face flies, but this requires frequent application. If face flies are an issue in your area, you should talk to your veterinarian about administering pinkeye vaccines as an added layer of protection for your residents- these vaccines typically need to be administered prior to the beginning of the fly season in order to be most effective.

Horn Flies (Haematobia irritans)

These flies look similar to stable flies, but are smaller (3-4mm) and do not have the stable fly’s checkerboard pattern. Horn flies tend to cluster along a cow’s back and sides. Unlike face flies, horn flies spend most of their life directly on the cow and feed on their blood; one horn fly may bite a cow 20-30 times over the course of one day. These bites are painful- cows affected by horn flies will often be seen twitching, kicking, and swishing their tails. Horn flies can also be vectors for certain diseases. Females lay their eggs in fresh poop, and their populations can grow quite quickly, with females laying up to 400 eggs. In areas with large horn fly populations, a cow could be infested with thousands of these flies. Areas with hot summer temperatures may see a decrease in horn fly populations during the hottest part of the year.

Horn flies can develop resistance to insecticides, which can make management difficult. Properly placed cow rubs or dust bags can help manage horn flies, but as mentioned earlier, if your herd consists of residents of varying sizes, it may be difficult to position the devices so that they make contact with everyone. Pour-on insecticide treatments can also be useful, but require regular re-application. Pour-on ivermectin can help manage horn flies for up to 28 days after application, but frequent use of ivermectin can contribute to internal parasites developing resistance to the drug. Because these flies lay their eggs in fresh cow poop, breaking up or removing poop from pastures and other living areas is helpful. Parasitic wasps can be especially effective in managing horn fly populations, and there has been some research about the use of plant extracts and essential oils. Neem extract, as well as the essential oils of tea tree, lemongrass, peppermint, eucalyptus, germanium, and catnip have shown varying degrees of efficacy on horn flies, as have home-made pyrethrum-based topical sprays.

Stable Flies (Stomoxys calcitrans)

These are biting flies that typically cluster on a cow’s legs. Stable flies (5-7mm) look much like house flies, but have a checkerboard pattern and biting mouthparts that project straight ahead. Their bites are very painful, and they feed one to three times per day, often biting a cow’s front legs. Affected cows are often seen stomping their legs and swishing their tail to avoid them. Groups may also huddle together to try to protect themselves.

Because they can travel many miles over the course of a day, controlling stable fly populations can be difficult. Topical treatment and self treatment products tend not to be effective control strategies. Instead, the best course of action is to focus on keeping things clean and removing areas where they lay eggs. These flies seek out wet areas with decaying plant matter to lay their eggs, and stable fly larvae may be found in wet hay and straw as well as composting bedding, decaying plant matter, algal mats, and poop that has formed an outer crust. Parasitic wasps may help manage populations, and there is some research regarding the use of plant extracts and essential oils. Camphor oil, peppermint, chamomile, and onion essential oils have been shown to repel stable flies from water buffalo for 6 days, and citronella, catnip, and lemongrass essential oils have also shown efficacy against stable flies.

House Flies (Musca domestica)

These flies are dull gray and about 6mm in length. They do not bite, instead feeding by sponging up various secretions, including blood from wounds, sweat, discharge from eyes, and saliva. Females are drawn to open wounds, especially those with pus or other drainage, as these are areas where they can feed and lay their eggs. This results in fly strike. Though they are mostly considered a nuisance, they have the potential to spread disease.

Regular cleaning is important to keep house fly populations under control, and certain species of parasitic wasps can also be helpful. Keep in mind that if you live near residential properties, a large house fly population at your sanctuary will likely affect your neighbors and could result in complaints against the sanctuary.

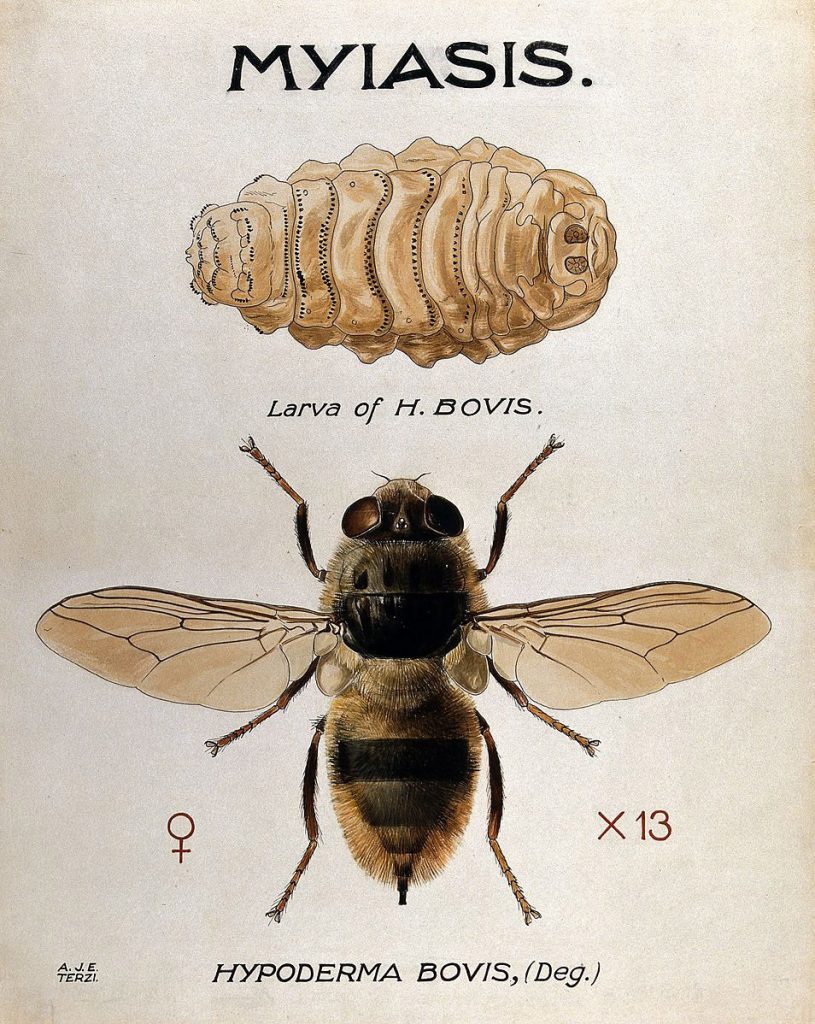

Heel Flies (Hypoderma bovis and Hypoderma lineatum)

These flies (also known as warble flies) look like honey bees, and while they do not bite cows, they cause significant agitation when attempting to lay their eggs on a cow, typically on the hair of their legs or lower body. Cows may be seen kicking at themselves to keep heel flies away and may even try to run from them. After the eggs hatch, heel fly larvae (called cattle grubs) pierce the cow’s skin and then migrate through their body for months. Each species has its own migration pattern, with the common cattle grub traveling to the mucous membrane of the esophagus, where they spend the winter, and the northern cattle grub traveling to the spinal column. Ultimately, both species travel to the cow’s back, where they puncture breathing holes through the skin (called “warble pores”) and then encyst, causing swelling that is often referred to as a “warble.” The larva remains here for 1-3 months before the mature grub (which is about 30mm long) emerges through a breathing hole and falls to the ground to pupate.

The cow’s tissues can be damaged during the migration process, and they can develop an inflammatory response if the larva dies in their body, which is why treatment and preventative measures must be timed appropriately. If treatment is administered when common cattle grubs are in the esophagus, the esophagus could swell causing the individual to develop bloat or even suffocate and die. If cattle grubs are killed while near the spinal cord, the cow may develop weakness in their back legs or even hind end paralysis, though individuals with paralysis often recover. Be sure to work with your veterinarian regarding the proper prevention for cattle grubs to ensure any treatments are administered at the correct time for your region to prevent adverse reactions. Also be aware that cattle grubs can affect other animals, including humans and horses. In some countries, cattle grub infestations are a reportable condition.

Horse Flies (Tabanus sp.)

These flies are big at approximately 25mm long. The females bite, and not only is this bite extremely painful, it can also spread anaplasmosis. Horse flies typically bite cows along their back or on their neck or side. Topical permethrin can help manage horse fly populations, but must be reapplied frequently. In some cases, you may not see a noticeable reduction in horse flies, despite proper use of insecticides. Dust bags and cow rubs used with permethrin insecticides can be effective strategies.

Deer Flies (Chrysops sp.)

Like horse flies, female deer flies bite, and their bite is very painful. These flies are 6-10mm long and typically bite cows along their back, on their neck, or on their sides. Control strategies are similar to those used for horse flies- permethrin topical treatments can be useful with frequent application. Properly placed dust bags or cow rubs with permethrin insecticide may be a more effective solution.

Creating a cohesive fly mitigation strategy can be complicated and frustrating. Be sure to work with experts in your area, identify strategies that are compatible with your philosophy of care, and thoughtfully evaluate their efficacy regularly!

Do you have a fly mitigation strategy that has worked well for your residents that isn’t discussed here? Let us know!

SOURCES:

Dung Beetle | University Of Wisconsin At Milwaukee

Dung Beetle Benefits In The Pasture Ecosystem | ATTRA

Dung Beetles And Their Role In The Nature

Fly Control 101: Tips For Controlling Flies On Your Farm | Ag Daily (Non-Compassionate Source)

5 Essential Steps For Fly Control On Cattle | Beef Magazine (Non-Compassionate Source)

Petroleum Product Poisoning in Cattle | Cattle Business in Mississippi (Non-Compassionate Source)

Invited Review: Environmental Enrichment Of Dairy Cows And Calves In Indoor

Housing | Journal Of Dairy Science (Non-Compassionate Source)

The Little Bugs That Do a Big Job!™ | Spalding Laboratories (Non-Compassionate Source)

Fly Predators Biology | Spalding Laboratories (Non-Compassionate Source)

How To Establish Dung Beetles In Pastures | Eco Farming Daily(Non-Compassionate Source)

Considering Feed-Through Fly Control This Year? | Drovers (Non-Compassionate Source)

Common Flies of Cattle | Kansas State University (Non-Compassionate Source)

The Face Fly | Neb Guide (Non-Compassionate Source)

Treatment Guidelines For Pasture Flies, Horn Flies And Face Flies | University Of Kentucky (Non-Compassionate Source)

Horn Fly | LivestockAnother term for farmed animals; different regions of the world specify different species of farmed animals as “livestock”. Veterinary Entomology (Non-Compassionate Source)

Featured Creatures: Horn Fly | University Of Florida (Non-Compassionate Source)

Stable Fly | Livestock Veterinary Entomology (Non-Compassionate Source)

Control Of Stable Flies And House Flies (Non-Compassionate Source)

House Fly | Livestock Veterinary Entomology (Non-Compassionate Source)

Cattle Grub Management | University Of Florida IFAS Extension (Non-Compassionate Source)

Botanically Based Repellent and Insecticidal Effects Against Horn Flies and Stable Flies (Diptera: Muscidae) | Journal Of Integrated Pest Management Volume 8, Issue 1 (Non-Compassionate Source)

Non-Compassionate Source?

If a source includes the (Non-Compassionate Source) tag, it means that we do not endorse that particular source’s views about animals, even if some of their insights are valuable from a care perspective. See a more detailed explanation here.