Introduction: Why Critical Thinking Matters in a Sanctuary Setting

In addition to providing refuge and lifelong compassionate care to formerly farmed animalsA species or specific breed of animal that is raised by humans for the use of their bodies or what comes from their bodies., many animal sanctuaries also strive to create spaces where humans can thoughtfully interact and (re)analyze their relationship with nonhuman animals in ways that will enable them to make kinder lifestyle choices. To help folks do this, it’s important that sanctuaries encourage them to think critically. Critical thinking is one of the most valuable cognitive skills to develop in a sanctuary setting because it provides folks with the tools they need to question the assumptions they hold, as well as the assumptions that others hold, about nonhuman animals, engage with the challenges facing nonhuman animals, come up with creative solutions, and take informed action.

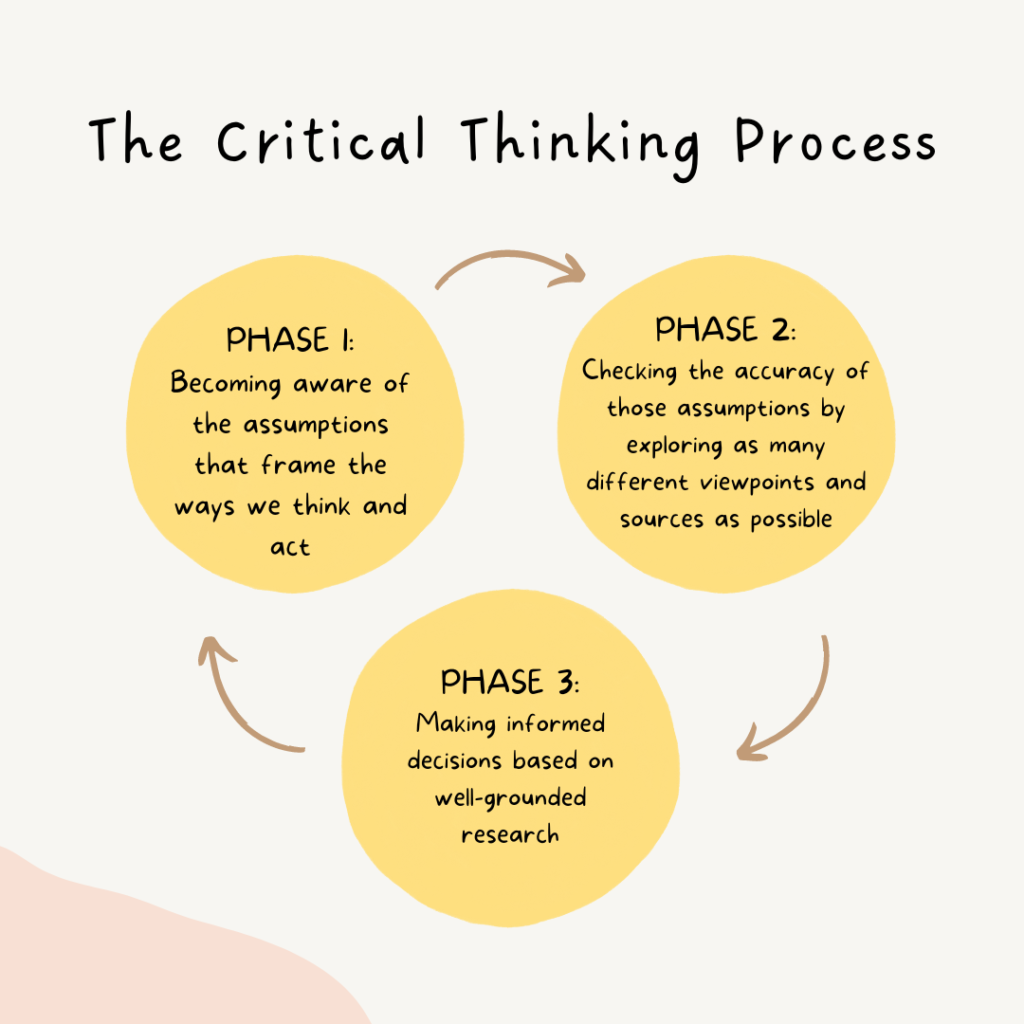

What is Critical Thinking?

In Teaching for Critical Thinking, scholar Stephen Brookfield defines critical thinking as the process of becoming aware of the assumptions that frame the ways we think and act, checking the accuracy of those assumptions by exploring as many different perspectives, viewpoints, and sources as possible, and then making informed decisions based on well-grounded research. Rather than just accepting the information we hold and receive as true, critical thinking requires us to challenge it and ask questions such as:

- “How do we know this?”

- “Is this accurate and well-grounded?”

- “Is this true for every case or just in this instance?”

- “Who said or wrote this?”

- “What biases might they have?”

- “Are there other sides to this story?”

- “What information is missing?”

- “How do I go about getting the information I need?”

- “Am I sure of my interpretation in this situation?”

- “Which beliefs and values shaped these assumptions of mine?”

- “What rationale supports my assumptions?”

- “Of the possible ways of thinking and acting I am considering, which one is most reasonable? Why are the others not as reasonable?”

Hypothetical Example of the Critical Thinking Process

When Patty was younger, she used to eat dairy products. She held the assumption that all cowsWhile "cows" can be defined to refer exclusively to female cattle, at The Open Sanctuary Project we refer to domesticated cattle of all ages and sexes as "cows." live in green pastures with their friends and family, naturally producing milk all the time and living out their lives in relative peace until they die of old age. She believed it was natural for humans to take milk from cows and consume it. Then, one day, she visited a sanctuary for farmed animals. While she was there, the sanctuary staff told her that what she believed about cows was not true (Phase 1). They told her that most cows in the dairy industry were actually forced to live the majority of their lives in miserable conditions: confined to indoor spaces, repeatedly and forcibly impregnated to produce milk, robbed of their babies, hooked up to mechanical milking machines, and then killed when they were only 4 or 5 years old. Patty was shocked and in disbelief. She thought, “How have I never known this?”. After her visit, she went home and read several articles online about cows and their life inside the dairy industry. She learned that the information the sanctuary had shared with her was correct (Phase 2). After her realization, she decided to no longer consume dairy products because she thought it was unnecessary and cruel (Phase 3).

How Critical Thinking Develops

The ability to think critically comprises a number of different skills and habits of mind that don’t fully develop until adolescence. However, the development of critical thinking builds from a set of foundational skills that folks can acquire in their earlier developmental stages as children. As sanctuary educators, it’s helpful to be aware of some of the developmental factors that can influence the progression of these skills and habits, and help build and reinforce them where we can when folks visit our spaces. Similar to empathy, critical thinking is an ongoing process and requires lifelong learning and practice.

Ages 5-9

Children this age are not yet ready to take on complicated reasoning or formulate detailed arguments about complex topics like animal exploitationExploitation is characterized by the abuse of a position of physical, psychological, emotional, social, or economic vulnerability to obtain agreement from someone (e.g., humans and nonhuman animals) or something (e.g, land and water) that is unable to reasonably refuse an offer or demand. It is also characterized by excessive self gain at the expense of something or someone else’s labor, well-being, and/or existence.. However, many of them can learn basic reasoning skills, build self-esteem, develop emotional management skills, internalize social norms that value critical thinking, and start to understand diverse perspectives that differ from their own – all foundational skills that can help set them up to confidently question assumptions and become successful critical thinkers later on down the road! As sanctuary educators, we can help children (and adults!) develop all of these skills by exposing them to new ideas about animals, encouraging them to try new things and ask lots of questions, providing clear explanations and answers, valuing the content of what they say, and showing pride in their cognitive maturation and growth.

Ages 10-12

Children this age begin to think more abstractly and reason more logically. This allows them to start formulating their own detailed arguments and identify errors in other people’s arguments about complex topics like animal exploitation. Children this age are also heavily influenced by puberty and its implications for their interests, self-esteem, social lives, and ability to manage their emotions. They also tend to generalize their arguments based on their own individual experiences. Sanctuary educators can help by challenging this age group (and adults!) with more complex discussions about nonhuman animals, encouraging them to reflect on alternative perspectives and the limitations of their own arguments, as well as the arguments of others, and providing them with plenty of opportunities to build up their self-esteem and work through their emotions as they process new information.

Ages 13+

At this age, critical thinking continues to build from the foundational skills acquired in earlier developmental stages, which allows children to strengthen their interpretive skills, critically analyze information, and formulate detailed arguments about complex topics like animal exploitation. However, kids this age are also heavily influenced by increasing peer pressure and anxieties over social belonging, which can lead to a conformity in ways of thinking and behaving that extends into adulthood. Sanctuary educators can help by encouraging this age group (and adults!) to acquire deep knowledge about complex topics like animal exploitation. This allows folks the opportunity to build confidence around their ability to call assumptions and sources into question and avoid an unreflective acceptance of the status quo. They can also help by providing this age group with lots of opportunities to identify, carefully analyze, and cope with disinformation and deceptive reasoning.

Barriers to Critical Thinking

In addition to being affected by age and brain development, the ability to think critically can also be impacted by several other factors, many of which can actually prevent adults from engaging in the process. As a sanctuary educator, it’s important to be aware of the risks and barriers that learners face as they contemplate the possibility of questioning their assumptions about animals and looking at things from new points of view. Here are some of the most common barriers to critical thinking.

Groupthink and Social Conditioning

One of the reasons a lot of folks resist thinking critically is because it often means looking at things from points of view that differ from the way they were socially and culturally conditioned to think, or “groupthink”. Groupthink is the tendency to adhere to a particular society or culture’s most acceptable way of thinking and behaving, which can suppress independent thought and action. Exploring what’s beyond groupthink can feel very threatening to someone’s sense of belonging. And indeed, what many of us initially find when we go beyond groupthink is the question of whether we actually do belong to our communit(ies), which presents us with tough questions, complicated decisions, and oftentimes, a lot of anxiety. Overcoming groupthink requires folks to break free from the status quo at the potential risk of cultural ostracism, which is what happens when the communities and support groups that have defined and sustained someone up until a certain point in their life, no longer feel the same sense of connection with that person. They might feel threatened by the way they’ve changed, and develop barriers to their belonging and participation in the community.

Egocentric Thinking

Viewing everything in relation to oneself is a normal human tendency, but it can lead to an inability to question one’s own assumptions and consider multiple viewpoints. However, understanding egocentricity as an inherent character flaw can actually help us remain actively aware of this tendency and work hard to counter it through consistent practice of alternative perspective-taking.

Personal Biases and Preferences

Personal biases and preferences are internalized beliefs, opinions, and attitudes that folks are often unaware of. They can reinforce stereotypes and assumptions, affect our ability to rationally analyze a situation, and influence our decision making. Personal biases can manifest in the following ways:

- Confirmation bias: the tendency to favor information that reinforces our existing assumptions and beliefs

- Anchoring bias: the tendency to favor the first piece of information we come across about a certain topic

- False consensus effect: the tendency to believe that most people share our viewpoint

- Normalcy bias: the tendency to respond to threat warnings with disbelief or minimization (e.g, “But that would never happen to me”)

Allostatic Overload

Allostatic overload refers to the cumulative effects that prolonged stress has on our physical and mental health. It can cognitively impair our ability to process information appropriately, which makes it much harder for folks to engage in critical thinking.

Impostership

Impostership is the fear of being a “fraud”. Thinking critically increases the chances of someone feeling like a fraud because the process often entails the realization that what they always naturally assumed to be true was, in fact, not true. This can make folks feel vulnerable and uncomfortable because it’s hard to admit they may have been wrong, and culturally, it’s not always safe to admit that. Anxiety around impostership is a common barrier to critical thinking and can lead folks to think, “I’m going to stop thinking critically because my life was much easier before I did that”.

Cognitive Fatigue

Cognitive fatigue (a.ka. “brain fog”) is when your brain feels exhausted and unable to function properly, which can impair the ability to think critically. It can be caused by a brain injury, but it is more commonly caused by a long-term lack of mental stimulation (e.g., an unchanging daily routine, social isolationIn medical and health-related circumstances, isolation represents the act or policy of separating an individual with a contagious health condition from other residents in order to prevent the spread of disease. In non-medical circumstances, isolation represents the act of preventing an individual from being near their companions due to forced separation. Forcibly isolating an individual to live alone and apart from their companions can result in boredom, loneliness, anxiety, and distress., repetitive tasks, poor boundaries between work and home life, etc.).

Lost Innocence

Scholar Stephen Brookfield defines “lost innocence” as the moment someone realizes there is no script, manual, technique, or person they can study and imitate that will help them solve all their problems. It’s the moment folks realize they have to take responsibility for their own learning and fumble their way through complex topics to the best of their ability. This can be a hard pill to swallow!

Instrumental Fluctuation

When folks think critically about something, it’s common for them to have a “breakthrough moment” – the feeling of “Ah-ha! THIS is the correct way of thinking or behaving. I get it now!”. This feels great up until the point that they try something based on their new knowledge and realize, “Wait, I think I need to reexamine this again. Perhaps that wasn’t entirely correct”. Brookfield refers to this ongoing process as “instrumental fluctuation” – the “take two steps forward, and then one step back” momentum that learners experience as they practice critical thinking, and even though it is entirely normal, it’s not always the most comfortable ride.

How to Foster Critical Thinking in a Sanctuary Setting

Part of the role of the sanctuary educator is to understand that all of these barriers and risks to thinking critically about animals exist, and then, to help folks who visit their spaces overcome them. But how do sanctuary educators effectively guide people through this process? How do we provide information and experiences in a sanctuary setting that safely encourage folks to question their assumptions, consider alternative perspectives, and then take informed action that benefits the well-being of animals? Let’s take a look at some of the ways we can foster critical thinking in a sanctuary setting.

Provide a Framework and Model the Process

For a lot of folks, visiting an animal sanctuary can be an incredibly jarring and emotional experience. It’s one of the very few places in the world where they are compelled to come face-to-face (literally) with the reality of their daily practices, lifestyle choices, and values. As anyone who’s already gone through this experience knows, it’s not an easy process. It can even feel quite threatening for a lot of people. As a sanctuary educator, it’s very helpful to gently introduce the process of thinking critically about these things by providing a basic framework and modeling it yourself in front of visitors! Remember Patty and the three phases of the critical thinking process she went through that we mentioned earlier in this resource? Let’s review!

- Phase 1: Becoming aware of the assumptions that frame the ways we think and act

- Phase 2: Checking the accuracy of these assumptions by exploring as many different perspectives, viewpoints, and sources as possible

- Phase 3: Making informed decisions based on well-grounded research

Utilizing this framework, you can model an analysis of your own ideas and practices related to nonhuman animals in front of the folks visiting your sanctuary, and explain the ways in which this changed your thinking and behavior. What kinds of assumptions did you become aware of that were influencing your thoughts and actions? How and when did you become aware of them? What did that realization feel like? How did you check the accuracy of those assumptions? What kinds of sources, alternative viewpoints, and counter assumptions did you contend with? What conclusion did you come to and what creative informed action did you take? How did you feel afterward? How do you feel now? By naming and modeling the process out loud, not only are you providing folks with a basic “grammar” to do it themselves, you’re also helping them become aware of some of the assumptions that might govern their own thinking, introducing them to new perspectives, and letting them know that thinking critically is a normal and shared phenomenon. For folks who are about to contend with complex topics like animal exploitation and their role in it, it can be very comforting to realize they are not the only ones going through this process. There are others who know exactly how it feels and they are in a safe space to explore it. Take-away advice for sanctuary educators: create a space at your sanctuary that makes the process of critical thinking feel normal and safe.

Model Good Habits of Mind

By modeling what your own critical thinking process looks like, you are also modeling good habits of mind. Habits of mind are life-related skills that help folks think strategically and solve problems creatively. They are also one of the fundamental building blocks of critical thinking, and include skills such as:

– Not accepting something as true until you’ve had the time to examine the available evidence

– Being open minded

– Having respect for the truth which means being open to having your opinion changed

– Having respect for others

– Being independent

– Being fair-minded

– Having respect for reason

– Having an inquiring mind rather than making assumptions

– Reframing problems as opportunities

– Analyzing the influences in your life (e.g. family, friends, social conventions, etc.)

– Questioning your own conclusions

Teach Folks How to Identify Assumptions

In addition to modeling an analysis of your own ideas out loud, it’s also helpful to have folks point out and question assumptions about animals that are held by other outside sources such as other individuals, groups, organizations, corporations, books, movies, t.v. shows, etc. You can even teach folks to look out for specific kinds of assumptions they are most likely to encounter:

- Causal assumptions: assumptions that claim to explain a series of events (e.g., “If I go veganAn individual that seeks to eliminate the exploitation of and cruelty to nonhuman animals as much as possible, including the abstention from elements of animal exploitation in non-food instances when possible and practicable as well. The term vegan can also be used as an adjective to describe a product, organization, or way of living that seeks to eliminate the exploitation of and cruelty to nonhuman animals as much as possible (e.g., vegan cheese, vegan restaurant, etc.)., I won’t get enough protein in my diet”)

- Prescriptive assumptions: assumptions about how things should happen or how we should behave (e.g., “A good daughter should eat whatever her mother gives her”)

- Paradigmatic assumptions: worldview assumptions that are seen as obvious or common sense. They are often so deeply embedded that when we are challenged about them, we don’t even think of them as assumptions (e.g., “Animals were put on Earth for humans to consume”)

After you’ve pointed out some of the assumptions of others together as a group, you can ask folks questions like, “Do you think any of these assumptions are well-grounded?”, “How do you know?”, “Which assumptions do you think are the strongest?”, “Which assumptions do you think need to be challenged and looked at more closely?”. Examine some arguments together and help folks separate the hard facts from the arguments or claims that a particular source is making.

Provide Opportunities for Folks to Reflect on Their Own Ideas and Practices

After you’ve modeled the critical thinking process, you can help folks start to think critically about their own ideas and practices. You can do this in a variety of ways. It could be as simple as asking folks questions like, “What kinds of assumptions do you think you hold about farmed animals?”, “Who or what influenced you to have those assumptions?”, “How do you know those assumptions are true?”, “What are the implications of those assumptions?”, “Do they make sense to you now?”, “What are some alternative ways of looking at farmed animals?”. Depending on the program, you could treat this as a social exercise and encourage folks in the group to help each other identify their assumptions, articulate their reasoning, and consider different viewpoints. You could also let folks contemplate these questions quietly since not everyone enjoys reflecting out loud. Graphics can come in handy here if you’re encouraging people to consider multiple viewpoints, such as those of farmed animals. No matter how you choose to provide folks with opportunities to think critically about their own ideas and assumptions, it’s important to remember that folks need to feel safe enough to do this. As a sanctuary educator, it’s important to refrain from judging anyone. Instead, encourage and celebrate the process! Ask folks what they want or need to explore more deeply to help guide them through this process, and always allow them plenty of time to reflect on how they’re feeling as they go through it. Thinking critically is hard work!

Foster Empathy Towards Farmed Animals

One of the best ways to encourage critical thinking in a sanctuary setting is to foster empathy towards farmed animals. This allows folks to participate more fully in the second phase of the critical thinking process, where they are asked to consider as many different viewpoints as possible prior to coming to a well-grounded conclusion in the third phase. This can be done in multiple ways and we encourage you to take a look at our extended resource on this topic here.

Help Folks Fight Cognitive Fatigue

Humans love routine. It makes us feel safe and can even help reduce stress. But monotonous routines, both physical and mental, can also become boring and restrictive, and cause cognitive fatigue. In order to think critically, we need to be exposed to challenging ideas that encourage us to make new connections and consider alternative ways of doing and seeing things. As a sanctuary educator, you can help folks fight cognitive fatigue by introducing them to new ideas that challenge them to see and think about farmed animals in exciting and innovative ways. Think about presenting your educational programming through various learning methods and materials: visual, auditory, written, kinesthetic, and multimodal.

Avoid Allostatic Overload

Similar to the development of empathy, the process of critical thinking can also be negatively impacted by the cumulative effects that prolonged stress has on our mental and physical health. As a sanctuary educator, it’s important to be extra mindful of the rhetoric and graphic images you use in your educational programming. Eliciting too much negative emotion for too long through distressing images, videos, and rhetoric can actually have the unintended consequence of hindering the critical thinking process. You can avoid allostatic overload by helping folks remain as calm as possible throughout your presentation and/or programming.

Helps Folks Minimize the Risk of Cultural Ostracism

The ways in which we view and think about animals is deeply embedded in our social and cultural conditioning, which is one reason why learning to relate to animals differently can be so challenging. Oftentimes, folks are afraid to consider alternative ways of being in relationship with animals out of fear that they will be ostracized by their communit(ies). As a sanctuary educator, you might even hear folks explicitly verbalize this fear: “I’ve heard that a lot of folks lose their friends after going vegan. Is that true?”. The answer is sometimes yes and sometimes no, but it depends on a lot of factors. One of the reasons folks might find themselves ostracized by their own communities is because of the way they’ve presented the new information they’ve learned or the new realization they’ve recently had. You can actually help folks minimize this risk by teaching them how to share what they’ve just learned at your sanctuary in ways that feel less threatening to their community members. Here are some helpful tips from Brookfield that we’ve adapted for someone who’s just visited a farmed animal sanctuaryAn animal sanctuary that primarily cares for rescued animals that were farmed by humans.:

- Instead of jumping into conversations with all of the new information they learned and why their family and friends should all change their habits and relationships with animals right away, encourage folks to begin these conversations by inquiring about the other person’s day and acknowledging what they did first: “How are you doing today?”, “What did you do today?”, “Thanks for being such a supportive friend and taking care of my dog while I was away today”.

- Encourage folks to wait for their friends and family to ask about their sanctuary experience first. If they don’t inquire about it, it’s helpful to initiate conversation into this topic by saying something like, “When I was at this sanctuary today, I realized how little I actually knew about animal agricultureThe human production and use of animals in order to produce animal products, typically for profit., and I had a real moment of awareness. It took me going there to realize that there are other ways to think about farmed animals”.

- Encourage folks to share any moments of anxiety or uncertainty they had or continue to have. This allows their community member(s) to feel like an ally as their friend or family member navigates a brand new experience and way of viewing the world.

Remember, it’s a Process!

Learning to think critically is a process, and not a particularly easy one! Treating it as such will help you and the participants in your sanctuary’s educational programming remain calm and confident, even as you stumble your way through some really complex topics together.

6 Ways to Foster Critical Thinking at Your Animal Sanctuary Infographic

Looking to share this information in an accessible way with other sanctuaries and supporters? Check out and share our infographic on six specific ways sanctuary educators can foster critical thinking about farmed animals with folks who visit their sanctuary space(s) and participate in their programming.

Sources

Critical Thinking Development | Reboot: Elevating Critical Thinking

Stephen Brookfield on Creative and Critical Thinking | DePaul Teaching Commons