Looking to better understand the residents in your care? This resource is intended to be valuable for anyone caring for residents who wishes to better understand their behavioral motivations, wants, and needs while keeping everyone safe and content. We will touch briefly on the basic categories of behaviors, innate and learned. Then we will cover the types of behaviors, such as social behaviors, resting behaviors, and so on. By the end of this resource, you will have learned some behavioral basics you can build upon going forward. This is just the first in a series on behavior intended to increase your general understanding of animal behavior, then narrowing the focus to species-specific resources from a sanctuary lens. Growing your understanding of resident behavior can help create more robust care practices for each resident and a safer and more compassionate environment for both staff and residents. Let’s jump in!

The Importance Of Understanding Behavior

Behavior provides a window into a resident’s world! With careful observation and record-keeping, behavior can tell us a great deal about what residents do when they are frightened, ill, happy, excited, and more! It can also help you learn what they prefer, enjoy, and dislike. What does normal behavior look like for them as a species? As an individual? From a sanctuary perspective, understanding residents’ behavior can significantly influence how you care for them, approach health checks, create social groupings, design enrichment plans, and build stronger bonds!

What Is Behavior?

While this may seem self-explanatory, let’s define the concept of behavior to ensure we are all on the same page. Over the years, various ethologists (scientists who study animal behavior) have provided different definitions of behavior, some oversimplistic and others overly complex. We are going to use Lee Alan Dutigan’s (Ethologist) definition of behavior from Principles Of Animal Behavior, 4th Edition:

“Behavior is the coordinated responses of whole living organisms to internal and/or external stimuli.”

At first glance, this may not appear to be the clearest definition, so let’s look at some examples to help explain it.

Examples:

- It is a hot sunny day (external stimuli). Jenny, the pig, moves to a shaded area of a mud wallow to cool down (response to external stimuli).

- Later, Jenny feels hungry (internal stimulus) and begins rooting around for food (response to internal stimulus).

Hopefully, you find these two examples helpful. Let’s take these examples and expound on them as we explore the two basic categories of behaviors that all behaviors stem from.

Categories Of Behavior

While this is an oversimplification, behaviors can fall into two categories: innate and learned behavior. Basically, this means instinctive or learned. Let’s dig a little deeper into both! You may be surprised at the different ways animals learn. If you want more information on learning theory, you can check out a resource that provides more details here.

Innate Behaviors

Innate behaviors are “hard-wired,” meaning the behavior is automatically performed the first time the individual is presented with the stimulus. While there are exceptions, a newborn mammal has a suckling reflex or knows how to find the nipple to suckle. If you place your finger in the hand of a human baby, their little hand will reflexively grasp your finger. Innate behaviors are predictable. Innate behaviors do not have to be learned; they are reflexive. Another example of this is nest-building in various species.

Learned Behaviors

While we could go into depth on learned behaviors and the various types and subtypes, we will keep this basic. This is behavior 101 after all! Remember, you can click on the link at the beginning of the section to learn more about learning. While innate behaviors are predictable, rigid, and reflexive, learned behaviors can be modified and picked up through different experiences and different means of learning. Let’s start with insight learning.

Insight Learning

Insight learning happens when someone has an “aha!” moment or a sudden understanding of the problem and solution. A common example of this in nonhuman animals is tool-making. For example, when presented with a narrow water tube containing a floating food item but the water is too low to allow the crow to reach the food, a crow may assess the situation and then have an “aha!” moment. The crow will then add pebbles to the tube, understanding this will cause the water level to rise and bring the treat close enough to grab. This isn’t something they instinctively knew how to do or learned by watching others (though this can happen too through observational learning). They made the connections on their own. “Oh! If I do blank, then blank will happen!”.

Associative Learning

Associative learning is when someone makes associations between two events or stimuli in their environment. The three types of associative learning are observational learning, classical conditioning, and operant conditioning. We will take a closer look at observational learning first.

Observational Learning

Observational learning is just what it sounds like: Someone sees someone performing an action and learns how to do the same themselves, or in some cases, learns how to avoid doing something that they observed led to a negative outcome. Let’s look at a couple of examples:

- Jimmy, the coolest llama dude in the pasture, practices his gate latch-opening skills. His prehensile lips help him flip the latch up, giving him access to a different area in his living spaceThe indoor or outdoor area where an animal resident lives, eats, and rests.. (We recommend double locking gates or using a carabiner or other such locking mechanism to prevent this from happening!) Nellie notices his behavior and comes in for a closer look. She sees that by using his lips and manipulating the latch enough, he opens the gate. She follows his example and, after some fumbling, finds she, too, can open gates by using her lips to move the latch up and down.

- Jenny, Annie’s best pal, roots around in the dirt and finds some mildly poisonous roots that she eats. This causes her to vomit. Annie, always close by, observes this and stays far away from those roots. She learned by watching Jenny to avoid the roots.

Classical Conditioning

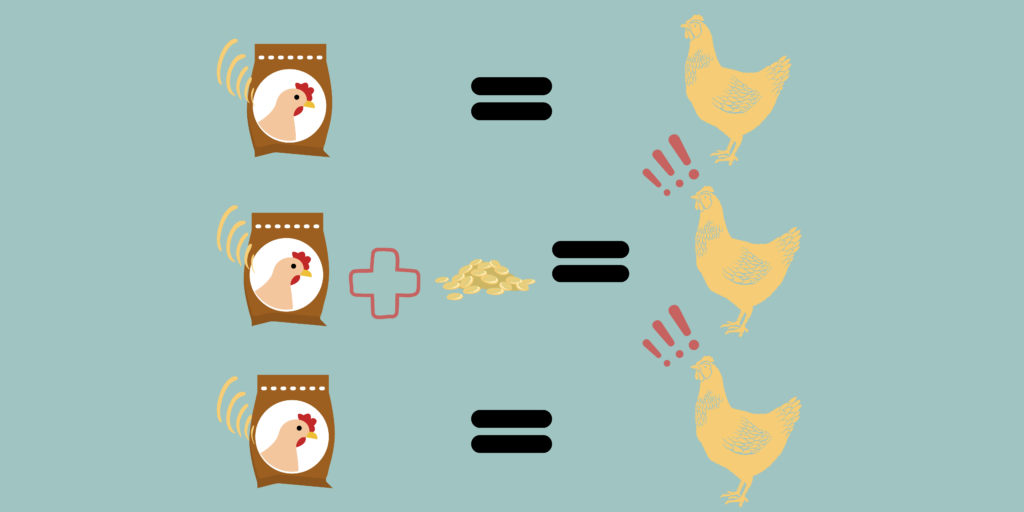

Classical conditioning occurs when someone associates one stimulus with another after repeated exposure. This is feelings-focused learning. Here is a visual example of the basic concept of classical conditioning, demonstrating how:

- At first, a neutral sound (the sound of a food bag crinkling) doesn’t initially elicit a physiological or behavioral response from Mr. Hobbs, the chicken. However, when the presence of food follows the neutral sound, the sound later elicits an excited response when Mr. Hobbs hears the sound of a food bag, even if it isn’t mealtime.

No doubt you are already quite familiar with this type of associative learning in residents! Let’s look at the last form of associative learning.

Operant Conditioning

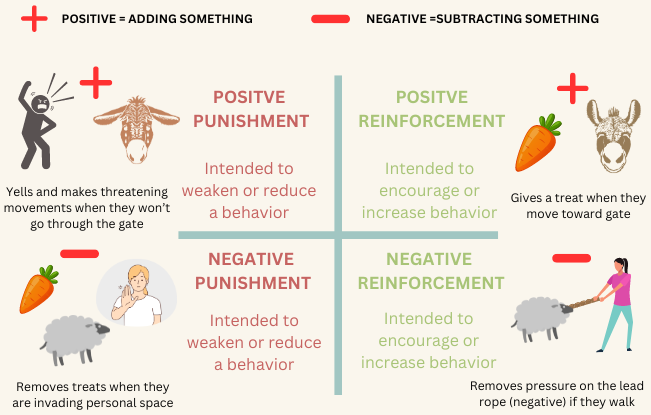

Operant conditioning is different from classical conditioning, as it occurs when someone learns to complete or increase a certain behavior or cease it because their behavior is reinforced or punished. There are two types of reinforcement and punishment: positive and negative. It is important to note that, in the context of operant conditioning, the word “positive” means added, and the term “negative” means subtracted or removed. In this context, positive doesn’t mean good, and negative doesn’t mean bad. See descriptions of each below and refer to the graphic above to better understand how operant conditioning works:

Positive reinforcement is when you give something pleasant to encourage a certain behavior.

Negative reinforcement is when you remove something aversive to encourage a certain behavior.

Positive punishment is when you add something aversive to stop a behavior.

Negative punishment is when you remove something that is considered pleasant to stop a behavior.

We will go further into “punishments” in future resources in order to address what is and isn’t appropriate in a sanctuary context. Positive punishment is generally inappropriate within a sanctuary environment, though there are a few careful exceptions.

Example:

- You need Posey, a goat resident, to come in from the pasture in the evening. She is often reluctant to do this. You begin working with Posey, positively reinforcing her behavior by returning to her indoor living space with a treat every evening around the same time. Posey has learned that if she returns to her indoor living space around a certain time, she will be rewarded with her favorite treat. (Positive Reinforcement)

- Delilah, a young horse resident, loves playing with the large exercise ball her caregivers put in with her and Sylvia, Rain, and Todo. However, sometimes Delilah gets a little too excitable and starts to try and engage in playing roughly with Todo. She runs between playing with the exercise ball and engaging Todo. Todo often becomes tired of this play and tries to end it by walking away. Delilah doesn’t always take the hint and chases Todo, which causes him to keep running. This can only go on so long before Todo, an older horse, becomes tired. Her caregivers take away the exercise ball to stop her overly excited behavior. (Negative Punishment)

Okay, while we could write a few detailed resources about learned behaviors (and we will in the future!) for now, we will leave it at that and briefly identify and define different kinds of behavior you will see in your resident population. Other types of learning we aren’t including in this resource include habituation, counter-conditioning, and desensitization. To learn more about learning, check out “Approaching Learning Opportunities With Residents: Concepts Of Learning Theory.” Don’t worry, this is also a foundational resource, but it discusses learning more deeply.

Types Of Behavior

Now that we have covered some of the basics of innate versus learned behaviors let’s dig into different types of behaviors that you will see displayed by residents. While this covers many types of behaviors, there are more, but we will expound on them in a future resource. To keep things simple, we will look at different types of social behavior, as well as foraging, antipredator, and resting behavior.

Social Behaviors

Social behavior can be defined as any interactions between two or more individuals, generally of the same species but can extend to interactions between different species. Different categories of social behaviors include cooperation, territoriality, altruism, social order, communication, affiliative, and agnostic behaviors. It can also include reproductive behaviors. We will start with behaviors related to social order.

Social Order Behavior

In the past, humans ascribed dominance theory to many social species. However, dominance theory for certain social species has been found to be misunderstood and misapplied to a number of species in recent years. Many people first think of wolves and the concept of an alpha that frequently fights others to maintain their alpha status. Wildlife biologists have debunked this theory in wolves, finding this behavior rare and now generally describe wolf packs more like a parent-family group.

That isn’t to say that hierarchies don’t exist or that dominance doesn’t play a part in some social species. A hierarchy is an order of individuals in a group that is based on certain characteristics or abilities. In many species, it may be parents and their offspring. Social order in some groups is based on age and/or sex. In others, it may be based on strength or size and dominance. In captive environments, natural social groupings are often disrupted. Learning about the species you care for and their natural social order can help you make decisions related to living arrangements and know what behaviors to be on the lookout for to ensure the safety and health of residents under your care.

Cooperative Behavior

Cooperative behaviors involve multiple individuals working together to achieve a common goal. For example, if a bison herd detects predators, they may form a circle around their young or weaker members to protect them. Elephants (a matriarchal society) will circle around one of their members who is giving birth to provide protection and sling dirt onto the newborn to hide their scent from predators. In certain predatory pack species, cooperative hunting is also a common behavior.

Affiliative Behavior

Affiliative behaviors are peaceful or friendly behaviors that develop, maintain, and strengthen social bonds. An example of this is allogrooming. This is where one individual grooms another, or they groom each other simultaneously. A number of studies have indicated that cowsWhile "cows" can be defined to refer exclusively to female cattle, at The Open Sanctuary Project we refer to domesticated cattle of all ages and sexes as "cows." bond with specific individuals, and allogrooming is witnessed in these friendships. Often witnessed among young group members, play behaviors can also be considered affiliative behaviors and learning and practice opportunities for skills they will need in adulthood.

Agnostic Behavior

On the other hand, agnostic behavior refers to any behavior related to fighting, including threat displays, confrontations, retreats, and placating and appeasement behaviors. This could look like stallions rearing at each other or residents fighting over or pushing away someone to access food resources. It could also look like male bettas flaring their gills and fluttering their fins in a threat display.

Territorial Behavior

A territory is an area someone establishes as their own or their group’s area, used for resource gathering (food and water), shelter, mating, and/or caring for their young. They may use marking behaviors through pheromones, urinating or defecating, or rubbing scent glands on the surrounding area to establish the boundaries of their territories. Other territorial behaviors may include agnostic behaviors, as listed above.

Altruistic Behaviors

Altruistic behaviors are those where an individual acts in a way that benefits another at a cost to themselves. There are different types of altruism and theories about this. Namely, interspecies altruism, intraspecies altruism, and reciprocal altruism. Examples of intraspecies altruism are worker bees that spend all their time ensuring their queen is fed and not reproducing themselves or an individual giving some of their food to someone else who cannot fend for themselves, which has been seen in several species. Examples of interspecies altruism are when one species adopts a member of another species as their young or herd/flockmate (recently seen when a group of beluga whales adopted a narwhal into their pod). Another example of this is Lulu, a mini-pig, who ran outside and lay down in traffic until someone stopped to help her human companion, who was in cardiac arrest. Another example that includes both intra and interspecies altruism comes from a news story where a hawk attacked a hen, and a rooster rushed to fight off the hawk, followed by a goat who charged the hawk until they flew away. (Check out our predator-proofing resource for birds). Please note that we do not recommend or support using residents as guards for other residents.

Reciprocal altruism is when someone performs seemingly selfless behavior but with the expectation or possibility of the recipient later helping them. “If I do this for them now, they will do this for me later.”

Communicative Behaviors

Social behaviors require communication, whether through vocalizations, body language, or scent marking. If Lucky the GooseUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated goose breeds, not wild geese, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource. stretches out their neck while walking toward you and hissing, he is communicating that he wants you to leave or desist whatever behavior you are doing. If Zephanie, a donkey resident, walks towards you with a relaxed posture and attentive ears in a forward position, they are likely coming to greet you (or see if you have treats!)

Reproductive Behaviors

Reproductive behaviors include everything from choosing or attracting a mate (courtship) to actual mating and caring for young. It can also include agnostic behaviors as two or more individuals confront, threaten, guard, or fight one another in an attempt to access their chosen mate. Other reproductive behaviors include nesting behaviors, choosing birth sites, and birth or laying.

In some mammalian species, it is common for a male to sniff a female individual’s urine and vulva in order to ascertain if she is in estrus and likely to be receptive to mating. You may have witnessed the Flehmen response in certain resident species. According to ZooAn organization where animals, either rescued, bought, borrowed, or bred, are kept, typically for the benefit of human visitor interest. And Wild Animal Medicine, “Flehmen is a behavior exhibited primarily by males, occasionally by females, in which the animal raises the nose into the air, with the mouth slightly open, to facilitate pheromone detection by an odor detection organ in the roof of the mouth.”

Foraging Behaviors

Foraging behaviors include identifying, searching for, and consuming food. In the wild, foraging behavior makes up a great deal of time spent each day. These behaviors will vary between species and depend on the behavior of the wild species that domesticatedAdapted over time (as by selective breeding) from a wild or natural state to life in close association with and to the benefit of humans species are descended from and the use for which humans bred and domesticated them. How they search for food and how they consume it can be affected heavily by environmental factors. In captive environments, many species are provided diets that do not allow them to perform natural feeding behaviors. This can result in physical and psychological health issues. If a species generally spends 11-14 hours searching for and eating food but receives all of their food in one place or eats a diet mostly of concentrates, they will have a lot of extra time. This can lead to frustration and boredom, which, in turn, can lead to stereotypic behaviors and health problems.

Antipredator Behaviors

Antipredator behaviors may include avoidance-type behaviors or agnostic behaviors. Avoidance behaviors may include hiding, remaining or becoming silent, choosing their location carefully, and keeping vigilant. There are other ways animals avoid detection by predators that aren’t always behavioral, such as mimicry of inedible items or poisonous/venomous animals. Think of walking sticks and certain species of brightly colored tropical frogs. However, that isn’t typical of traditionally domesticated and farmed species.

When an animal encounters a predator, they may flee (flight), freeze, or fight. Different species may have different reactions. Such is the case with horses and donkeys. Both are equines, but they evolved in different environments, making horses more prone to flight because their ancestors lived in more open spaces in large groups. On the other hand, donkeys lived in smaller groups in areas where the topography was rocky, making them more likely to successfully survive an encounter with a predator by standing their ground together.

Resting Behaviors

Resting behaviors vary among species. Some species can and do rest while standing, whereas others may lie down or “sit.” Posture is just one aspect of resting behaviors. The state of wakefulness is another. Resting, drowsing, and sleeping are three types of resting behavior. An individual, let’s say a cowWhile "cow" can be defined to refer exclusively to female cattle, at The Open Sanctuary Project we refer to domesticated cattle of all ages and sexes as "cows." resident, may rest in a recumbent position in a state of wakefulness. A horse resident may drowse (a state in and out of wakefulness and sleeping) while standing and shifting their weight. A chicken resident may huddle down with their head nestled into their breast and sleep. Some species have someone in the group stand guard, whereas others only sleep in protected areas or during certain times when predators are less likely to be about.

With that, we will wrap up Behavior 101. We hope this resource has proven helpful. We encourage care staff to consider, research, and discuss how their resident species’ population behaves in each area. Understanding how a species has adapted to perform certain behaviors will help care staff provide the best possible care for residents. However, always remember that everyone is an individual and may behave in ways outside the norm of their species.

SOURCES

Broom and Fraser’s Domestic Animal Behaviour And Welfare 6th Edition | Donald M. Broom (Non-Compassionate Source)

Principles Of Animal Behavior 4th Edition | Lee Alan Dugatkin (Non-Compassionate Source)

Domestic Animal Behavior For Veterinarians And Animal Scientists 6th Edition | Katherine A Houpt (Non-Compassionate Source)

Affiliative Behaviors | Encyclopedia Of Animal Cognition And Behavior (Non-Compassionate Source)

Social Licking Patterns In Cattle (Bos Taurus): Influence Of Environmental And Social Factors | Applied Animal Behavior Science (Non-Compassionate Source)

Displays Of Animal Altruism | Leslie Tsen Jing Wei, Adam Weinberger, Ismail Sukkar and Julie M. Fagan, Ph.D, Rutgers University (Non-Compassionate Source)

The Social Behaviour Of Cattle-Chapter 5 | Social Behaviour In Farm Animals (Non-Compassionate Source)

Altruism In Animals And Classification : A View | Anusandhan Vatika-Researchgate

Reproductive Physiology Of The Ram | Current Therapy In Large Animal Theriogenology (Second Edition) (Non-Compassionate Source)

Flehmen | Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine (Sixth Edition), 2008 (Non-Compassionate Source)

Adopted Lone Narwhal Traveling Among Belugas Could Produce Narluga Calves | Smithsonian Magazine (Non-Compassionate Source)

Hero Farm Animals Rescue Chicken Buddy From Hawk In Dramatic Video | New York Post (Non-Compassionate Source)

Hero Animals: The Pig That Called for Help | Big Wave Productions – National Geographic (Non-Compassionate Source)

Non-Compassionate Source?

If a source includes the (Non-Compassionate Source) tag, it means that we do not endorse that particular source’s views about animals, even if some of their insights are valuable from a care perspective. See a more detailed explanation here.