We Have Two Podcast Episodes On This Subject!

Want to learn about this topic in a different format? Check out our episode of The Open Sanctuary Podcast introducing the concept of agency or our follow up episode about fostering farmed animal agency at sanctuaries!

Resource Acknowledgement

This resource was written in collaboration with Emily Tronetti of Coexistence Education and Consulting. Emily specializes in adult humane education and applied animal behavior. She is passionate about helping advocates and organizations cultivate compassionate coexistence through teaching about and supporting the agency and wellbeing of other animals. We are so grateful for her collaborative efforts and contributions to The Open Sanctuary Project.

This Resource is Part of a Series!

This resource is the first in a series that explores agency and consent in farmed animalsA species or specific breed of animal that is raised by humans for the use of their bodies or what comes from their bodies. and how the application of agency-centered practices in sanctuary settings can enhance resident well being. To read the second resource of this series, “A Guide to Fostering Farmed AnimalA species or specific breed of animal that is raised by humans for the use of their bodies or what comes from their bodies. Agency in Sanctuary Education”, click here!

Non-Compassionate Sources

We at The Open Sanctuary Project disavow animal experimentation and any “use” of animals for human purposes. Because compassionate studies on valuing the personality, intelligence, and unique attributes of many nonhuman animals are rare, in this resource, we draw from existing sources that may be non-compassionate. Still, we may use the information we find to improve the lives of residents. We strive towards a future when compassionate, non-exploitative, and non-invasive research is the norm. In the meantime, we will work with what we have to help sanctuaries help animals as effectively as possible. You can read a little bit more about our non-compassionate source policy here.

Introduction

This resource is an introductory guide for animal sanctuary staff and volunteers who are interested in learning about agency in farmed animals and how the application of agency-centered sanctuary practices can enhance resident wellbeing. This resource is also a prerequisite to two other forthcoming resources for sanctuary staff and volunteers that go into much more depth about fostering agency in farmed animals in sanctuary education and sanctuary caregiving.

Resource Goals

By the end of this resource, readers will be able to…

- Define agency

- Understand what agency looks like in farmed animals

- Understand the negative impacts of suppressing and/or denying agency in farmed animals

- Understand the positive impacts of fostering agency in farmed animals

- Understand why agency is important in a sanctuary setting

- Recognize the inherent challenges in centering agency in a sanctuary setting

- Identify agency-centered sanctuary practices

What is Agency?

Agency is the capacity of a living being to engage with their environments and make choices for themselves based on their own preferences, needs, and desires.1,2 For the purpose of this resource, we have identified five key characteristics of agency that are crucially important to understand in the context of an animal sanctuary.

- Agency is vital to and shared across all animal species, human and nonhuman.

- Agency is integral to the health and wellbeing of all animals, human and nonhuman.

- Agency is relational, meaning that it’s not only a quality of individuals but something that emerges from our relationships with others and our environment.1 In other words, our ability to exercise agency is dependent upon how it is taken up (or not) by others.

- Agency is intentional and spontaneous, meaning the decisions we make and actions we take can be intentional or spontaneous, intuitive, habitual, and automatic.1 Our ability to act with intention or react intuitively to our environments and experiences is fundamental to our freedom.

- Agency is dynamic. In other words, agency requires that we have the ability to change our minds, say no, and have these choices acknowledged and respected.

What Does Agency Look Like in Farmed Animals?

While agency matters to all animals, human and nonhuman, how that agency is expressed looks different depending on the species and the individual.3 Everyone has a unique way of engaging with their environment and making decisions regarding things like food, exercise, rest, social interaction, physical contact, play, exploration, problem-solving, communication, and so on.4 Consider, for just a moment, two of your sanctuary or rescue companions that are different species. What are their favorite foods? Who are their best friends? What kinds of activities do they enjoy doing each day? How do they communicate with others? Now, briefly consider the same questions with two of your sanctuary or rescue companions that are the same species. It doesn’t take long to realize that no two individuals are ever exactly alike, whether they are the same species or not! While most of us in the sanctuary and rescue communities already know this, it can be helpful to read about and see some more specific examples. There is a lot written about the differences in how farmed animals express agency.3, 5, 6, 7 There are also a lot of photos that demonstrate this. Below, we’ve included a gallery of various farmed animals and sanctuary residents expressing their agency (both intentionally and spontaneously) in their own individual- and species-specific ways.

The Suppression and Denial of Agency in Farmed Animals

“As long as they have been farmed, farmed animal species’ lives have never been wholly oriented around their own flourishing or autonomyThe ability for individuals to have access to free movement, appropriate food, and the ability to reasonably avoid situations they wish to avoid. over their lives and bodies—farming animals to extract their life energies, their reproductive processes, and their very bodies is fundamentally at odds with their flourishing.”

– Kathryn Gillespie8

Sadly, farmed animals living within modern agricultural settings have their agency systematically suppressed and denied in nearly every single way. In the physical sense, they are genetically manipulated, forcibly maimed, confined to inadequate living spaces, and given highly processed “feed” to make them gain weight and grow rapidly. These conditions and practices often result in injuries and chronic disabilities, which further impact their agency.9 They are also typically denied the opportunity to live a natural lifespan. In the social-emotional sense, farmed animals are consistently denied the ability to explore, play, create, solve problems, control their relationships and social interactions with other animals (including humans), and engage in other activities that they find enriching. They are also often subjected to forced separation from their families and friends.

It will likely come as no surprise that the immediate and cumulative physical, social, and emotional effects of such agency-suppressive practices are overwhelmingly negative for all individuals. Despite our efforts as animal sanctuaries to counter these normative constraints by providing compassionate care and forever homes to farmed animals, the residents in our care remain in captivity with us nonetheless. As such, it is of vital importance that we strive to create spaces for them to exercise their agency as much as possible. Failure to do this can lead to a decline in their social, emotional, and physical wellbeing in ways that can be sadly similar to what they experience in modern agricultural settings. Here are some of the negative effects of agency suppression and denial in farmed animals:

- Deprivation of positive feelings associated with the ability to make choices (e.g. joy, excitement, satisfaction)4

- Increase in boredom, depression, helplessness, fear, and anxiety, which can lead to distrust of humans and dangerous behavior2, 4, 13

- Underdeveloped competence and an inability to solve social conflicts appropriately with other animals, particularly when unexpected things happen4, 14, 15, 16, 17

- Increase in illness, injuries, and chronic disabilities4, 10, 11

- Decreased ability to heal from injuries and illness, and therefore, an increase in pain12

The Impact of Supporting Agency in Farmed Animals

Now that we know some of the negative effects of agency suppression and denial, let’s take a look at some of the positive effects of supporting agency in farmed animals.

- Increase in pleasurable emotional experiences and positive feelings (e.g., joy, excitement, peace, satisfaction, confidence)3, 5, 20

- Decrease in fear and anxiety21

- Increased competence and social coping capabilities, particularly when unexpected things happen3

- Ability to more fully express natural species-typical potential and fulfill daily needs (e.g., adequate nutrition)

- Enhanced physical fitness and healthier bodies18

- Better overall immunity and increased ability to heal from injuries and illness12

- Increased life span19

Why is Agency Important in a Sanctuary Setting?

In direct opposition to the prevailing structure of animal exploitationExploitation is characterized by the abuse of a position of physical, psychological, emotional, social, or economic vulnerability to obtain agreement from someone (e.g., humans and nonhuman animals) or something (e.g, land and water) that is unable to reasonably refuse an offer or demand. It is also characterized by excessive self gain at the expense of something or someone else’s labor, well-being, and/or existence. in modern agriculture, animal sanctuaries strive to create spaces where the residents in their care can feel as healthy, safe, and free as possible. In our efforts to do this, we implement a variety of thoughtful practices that promote their wellbeing. We provide residents with healthy diets and compassionate veterinary care, work to reduce their risk of being exposed to infectious diseases through careful biosecurity protocols, and so on. As part of the larger movement for animal liberationA social movement dedicated to the freeing of nonhuman animals from exploitation and harm caused by humans., these efforts are crucial, not only because of the qualitative difference they make in the lives of formerly farmed animals but also because of the symbolic value they have in demonstrating that different and less harmful ways of being in relationship with them are possible.22

In light of our goals as sanctuaries as well as our understanding that agency expression is vital to the health and wellbeing of all animals, it is critically important that we implement thoughtful practices in our spaces that also allow residents to express themselves as fully as possible, make choices for themselves, and interact with others as individuals whose interests are worthy of consideration and respect. This is where agency-centered sanctuary care, education, and outreachAn activity or campaign to share information with the public or a specific group. Typically used in reference to an organization’s efforts to share their mission. come in.

Recognizing the Inherent Challenges of This

In practice, the task of allowing farmed animals to exercise full agency over their lives is not only challenging but impossible. As animal sanctuaries, we are forced to contend with the unfortunate realities and consequences of domestication and exploitation, which require us to care for formerly farmed animals in continued captivity and ensure their safety. From juggling the varying medical, dietary, psychological, social, and spatial needs of multiple individuals to working within the confines of limited resources, balancing our efforts to provide as much freedom as possible with the necessity to retain some degree of control over the lives of farmed animals is no easy feat.22 In spite of this, animal sanctuaries can and should continue to work through these challenges and contradictions by actively exploring and practicing new ways to center and enhance the agency of their residents as much as possible. We’ll explore how sanctuaries can do this in the following section.

Agency-Centered Sanctuary Practices

There are a variety of agency-centered practices that animal sanctuaries can implement to enhance resident wellbeing. For the purpose of this introductory resource, however, we’re going to provide an overview of some of the important but more general agency-centered sanctuary practices. If you are interested in more specific guidance regarding sanctuary education and caregiving practices that center resident agency, we encourage you to check our website again soon. In just a few months, we will be releasing a comprehensive resource that specifically covers farmed animal agency in the context of sanctuary education. We are also in the process of developing a resource that will take a much deeper dive into farmed animal agency in the context of sanctuary caregiving. So, please stay tuned!

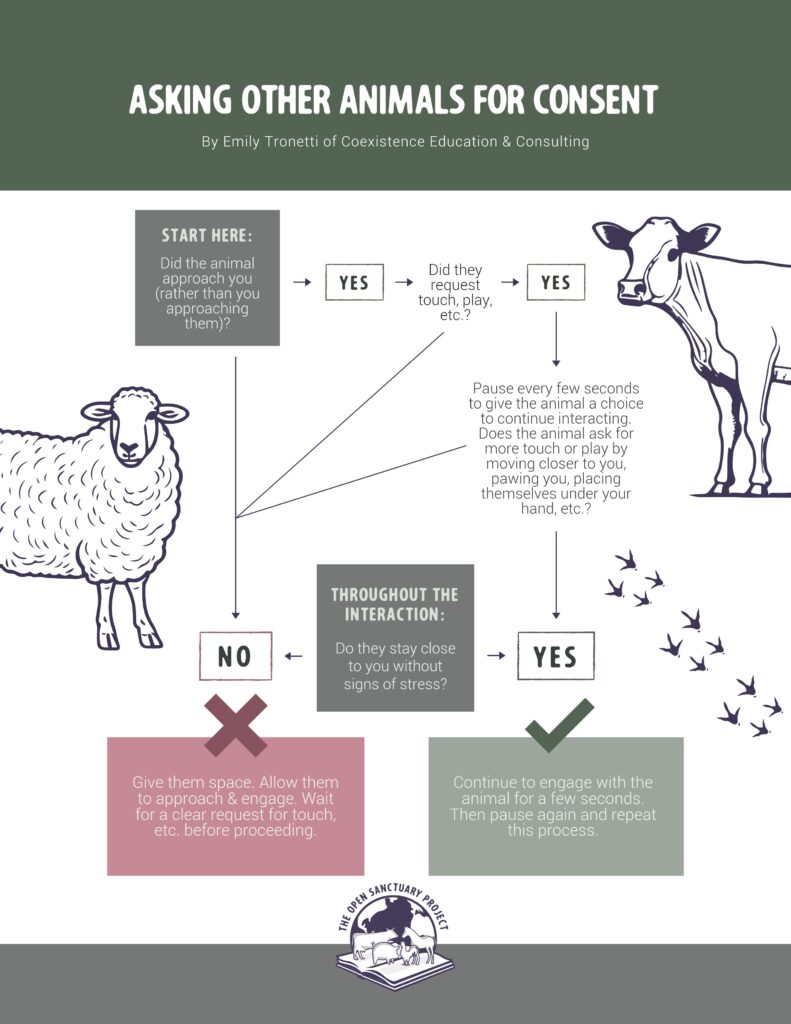

Nurture Consent-Based Practices and Interactions

One important way sanctuaries can and should nurture the expressions of resident agency is by nurturing consent-based practices and interactions with them. Generally, consent refers to giving permission, approval, or agreement.23 Consent is directly linked to agency in that, in order to fully support the agency of another, we must obtain their consent to engage with them. Although consent is typically associated with humans, it matters just as much to other species, too. Farmed animals offer consent or denial of consent through nonverbal communicative cues such as their behaviors and body language.24 Unfortunately, reading the body language of farmed animals and interpreting consent and non-consent with them doesn’t always come naturally to us humans. So, it’s important to take time to learn about species-typical and individual behaviors, body language, communicative cues, and emotions through careful research and observation. There are also a number of other skills that sanctuary staff and volunteers can embody and cultivate in themselves and others to help nurture consent-based interactions with residents. Skills like mindfulness, critical reflection, and empathy, for example, help us better understand what residents might be feeling and experiencing and allow us to make more informed, compassionate care- and education-related choices that center their agency.25, 26

While there’s much nuance and complexity that occurs in consent-informed interactions, in general, they should include acknowledging the individual, paying attention to what others are communicating with us, respecting choice, and not forcing interactions. Of course, as we’ve mentioned, there will be times when it is necessary to override the agency of the residents at your sanctuary (e.g. medical care). Nonetheless, it’s important to have at least a basic understanding of what a consent-based interaction looks like so your sanctuary can strive for them whenever possible. The graphic below can serve as a general guide that can be shared with sanctuary staff, volunteers, and visitors as you learn more about what consent looks like and how it varies by species and individual.

Include Residents and Caregivers in the Decision-Making Process

Another important way to support the agency of sanctuary residents is to include them and their primary caregivers in any decisions you are making that may impact them27. This enables you better to know when it is and is not appropriate to override their agency and make decisions on their behalf. Learning this can be incredibly challenging. While there is no one-size-fits-all approach to doing this, there are some things you can do at your sanctuary to make it a bit easier.

One of the most vital steps to take when you are making sanctuary-related decisions that may impact the residents is to collaborate regularly with the caregiving staff. As staff who work directly with the residents on a daily basis, caregivers are often able to offer unique insight into the lived realities and experiences of certain species and individuals, as well as the potential effects a particular practice, activity, program, or event might have on them.

Another way to determine whether or not it’s appropriate to override resident agency is to stay mindful of speciesismA form of discrimination based on species membership; the belief that different species of animals deserve different ethical considerations regardless of whether they have similar needs or interests. within your own organization and check your biases28. Even in sanctuary settings, certain species are sometimes unconsciously relegated to a lower status than others. If this is the case at your sanctuary, it’s important to implement practices that ensure they receive the same consideration and decision-making power as all of the other species. It’s equally important to stay mindful of ableism within your organization28. It is extremely challenging to juggle the varying complexities and consequences of domestication and animal exploitation. However, being domesticatedAdapted over time (as by selective breeding) from a wild or natural state to life in close association with and to the benefit of humans, disabled, and dependent on others does not mean the residents are incompetent or incapable of making decisions on their own. Oftentimes, residents know better than we do about what’s in their best interest, and it’s important for us to allow them to express this whenever it’s possible and appropriate. Of course, this isn’t always the case. So, in some circumstances, it can be helpful to provide your sanctuary’s staff and volunteers with specific operational criteria to help them make appropriate decisions about whether or not a resident’s choice should be respected29. One such criterion might be that caregiving staff must be able to clearly explain what their justifications are for overriding resident agency when they are making a care-related decision. For example, in situations where the residents are unable to understand important information about why your staff wants to override their agency, such as to vaccinate a group of individuals to prevent a deadly virus, your staff will likely determine they have good reason to override it.5

Set Up Agency-Centered Living Spaces

When we are considering how to foster the agency of farmed animals in sanctuary settings, it’s critically important to consider the types of living spaces we are providing them. Here are some of the ways you can set up agency-centered living spaces for the residents at your sanctuary:

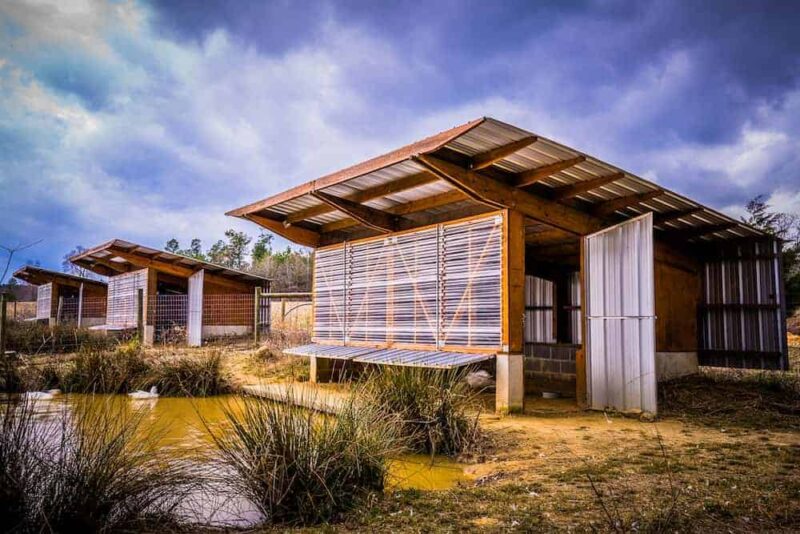

Co-Create Living Spaces

All animals benefit from being able to make choices about what their environments look like.3 Did you know that you can uniquely design and co-create your sanctuary’s environment(s) through human and nonhuman involvement? Yes, you can, and you should! In fact, there is an entire framework to help you create living spaces that are stable, rich, and complex in which residents can develop and to which they can respond. It’s called animal-centered design. While we’ve got a whole resource dedicated to this topic that we encourage you to take a close look at, essentially, the driving principle behind animal-centered design is to create living spaces that go beyond just providing protection from the elements and security from predators to providing a habitat that the residents might choose for themselves. It’s important to note that animal-centered design does not look one particular way. It emphasizes that each habitat or living spaceThe indoor or outdoor area where an animal resident lives, eats, and rests. should look different depending on varying factors such as the species, the individual, the setting, the season, and more. Animal-centered design asks questions like, “What kind of space might [insert species/individual] design for themselves if they could?”

Photo Credit: Daniel Turbert / The Sentient Project

In addition to utilizing frameworks like animal-centered design, your sanctuary should also consider how it can set up living spaces that the residents can manipulate and (re)structure on their own in ways that are consistent with their safety. One way to do this is by providing dynamic enrichment opportunities for the residents to engage in. There are so many ways your sanctuary can make resident living spaces more enriching, and we’ve got a ton of resources on this topic! The most important thing is that the forms of enrichment you provide are meaningful and challenging but also skill-appropriate and safe for their given species and for them as individuals.4

Enhance Mobility

One very important aspect of agency is the ability to move the way you want to. With this in mind, your sanctuary should create and modify living spaces in ways that allow residents to do this as much as possible, so long as they are consistent with their safety and contextual limitations. This includes all aspects of moving in a way that allows residents to get outside, feel a sense of overall safety, and have control over who and what they interact with, when they interact with them, and how that interaction occurs, including the type of interaction (e.g., direct vs. indirect), duration, and location. Consider, for example, the potential impact of things like trees, shrubs, designated safe spaces, and other comfortable forms of coverage that allow residents to hide or get away from things like the elements, predators, onsite visitors, and other residents. It’s important to provide residents with a variety of options so they can choose these types of spaces for themselves.

Covered Spaces: Their Benefits and Limits

Some sources suggest that providing covered areas within a fenced space (or unfenced in the case of free-ranging) will provide farmed bird species like chickens ample protection against aerial predators. These sources suggest that when bird residents detect an aerial predator, they will run for cover, foiling the predator’s plans. While it is true that birds may seek cover when an aerial threat is detected, this is NOT a fail-safe method of predator-proofing for your residents. Some predators may still be able to reach a bird resident or may sit and wait until they come out again. The best way to protect against aerial threats is to use aviary netting or something similar to prevent aerial predators from accessing outdoor spaces. However, while netting or galvanized hardware cloth will keep aerial predators out, it may still leave residents feeling vulnerable if they do not have areas of solid cover. Therefore, we recommend adding non-toxic tall vegetation (particularly evergreens for year-round coverage) and/or man-made protective structures to the space as well. While these elements on their own may not fully protect residents from predators, they will provide a sense of safety and add interest and enrichment to the space, giving your residents options to choose where they’d like to spend their time. For more information and inspiration on this particular topic, please check out our resource titled Predator-Proofing for Bird Residents at Your Animal Sanctuary.

Provide Self-Structuring Social Environments

Whenever possible, it’s important to allow sanctuary residents the opportunity to structure their own social environments and form their own social groupings. This includes providing ways for residents to choose their friends and have control over their interactions with others, both nonhuman and human. This, of course, will be impacted by various safety and group composition factors that your staff should carefully consider, including the species, age, and health of each resident.

Respect Resident Routines

Routines provide farmed animals with a sense of security, pleasure, and stimulation.1 They can also provide positive and meaningful opportunities for them to exercise agency when they are allowed to negotiate, modify, and vary them.1 This raises a few important questions for animal sanctuaries to consider. Is it okay to disturb residents while they are carrying out their routines (e.g., foraging, eating, sleeping, etc.)? Undoubtedly, there are tasks your sanctuary performs in order to properly care for the residents that require you to occasionally disrupt their routines (e.g., compassionate medical care). In light of this, your sanctuary should ask itself how it might co-create practices and routines with the residents that center their agency, limit disruption, and allow your staff to responsibly complete their tasks.

Track and Evaluate Your Sanctuary’s Agency-Centered Practices

Another important way to support the agency of the residents is to track and evaluate your sanctuary’s existing agency-centered practices.1 You can do this by writing down all the ways your sanctuary is currently supporting the agency of the residents. It can also be incredibly helpful to write down the ways your sanctuary is potentially suppressing or denying the agency of the residents. Review your practices, modify them, and continue to identify and explore new ways to center and support agency.

Conclusion

In the vast majority of circumstances around the world, humans are suppressing and denying the agency of farmed animals. In light of our goals as sanctuaries, as well as the complex circumstances and environments in which we carry out our work, it is imperative that we explore meaningful ways to counter these normative constraints and enhance agency in farmed animals. While every sanctuary will have its own ways of conceiving and operationalizing this task, we hope this resource has been a helpful introduction to get you started. For additional help moving toward more agency-centered practices and ways of being in relationship with the farmed animals at your sanctuary, please take a look at the list of questions below that are intended to help guide your organization.

Guiding Questions

- In what ways can you empower your sanctuary’s residents to exercise agency as much as possible, given the reality that it will always be limited to some extent in captivity?

- What other kinds of challenges and/or barriers currently make it difficult to integrate agency-centered practices into your particular sanctuary?

- Given the specific challenges and limitations, how might meaningful forms of agency be made possible at your sanctuary?

- If your sanctuary’s residents had full freedom to choose how they want to live, what would that look like? Where would they want to be? What would their environment look like? What would they want to do each day? Who would they want to be with?

- How does each resident at your sanctuary communicate consent and non-consent? How does this change depending on the context they are in?

- How can your sanctuary co-create and alter its spaces in response to residents’ preferences and actions in a way that is also consistent with their safety and other contextual limitations?

- How can your sanctuary co-create practices and routines with the residents that center their agency, limit disruption, and allow your staff to complete their tasks responsibly?

- Do sanctuary staff and volunteers feel like their agency and wellbeing are supported in your sanctuary? If not, how might this impact their ability to support the agency and wellbeing of the residents?

We’d Love to Hear How it’s Going!

Has your organization explored or implemented any new agency-centered practices since reading this resource? Please send us an update on how it’s going via our contact page! We’d love to hear how this resource has been helpful for you!

External Sources

- Animal Agency in Community: A Political Multispecies Ethnography of VINE Sanctuary | Politics and Animals

- The 2020 Five Domains Model: Including Human–Animal Interactions in Assessments of Animal Welfare | Animals (Non-Compassionate Source)

- Animal Agency, Animal Awareness and Animal Welfare | Animal Welfare (Non-Compassionate Source)

- Environmental Challenge and Animal Agency | Animal Welfare (Non-Compassionate Source)

- Interspecies Justice: Agency, Self-Determination, and Assent | Philosophical Studies

- Socio-Spatial Relationships in Dairy Cows | Ethology: International Journal of Behavioural Biology (Non-Compassionate Source)

- Long-Term Familiarity Creates Preferred Social Partners in Dairy Cows | Applied Animal Behaviour Science (Non-Compassionate Source)

- An Unthinkable Politics for Multispecies Flourishing Within and Beyond Colonial-Capitalist Ruins | Annals of the American Association of Geographers

- Beasts of Burden | Sunaura Taylor

- Assessment of the Duration of the Pain Response Associated with Lameness in Dairy Cows, and the Influence of Treatment | New Zealand Veterinary Journal (Non-Compassionate Source)

- A Cross-Sectional Study of the Prevalence of Lameness in Finishing Pigs, Gilts and Pregnant Sows and Associations with Limb Lesions and Floor Types on Commercial Farms in England | Animal Welfare (Non-Compassionate Source)

- Effects of Attention and Rewarded Activity on Immune Parameters and Wound Healing in Pigs | Physiology and Behavior (Non-Compassionate Source)

- Mental Health and Well-Being Benefits of Personal Control in Animals | Mental Health and Well-Being in Animals, 2nd Ed.

- Individual Housing During the Play Period Results in Changed Responses to and Consequences of a Psychosocial Stress Situation in Rats | Developmental Psychobiology (Non-Compassionate Source)

- The Playful Brain: Venturing to the Limits of Neuroscience | Sergio Pellis and Vivien Pellis (Non-Compassionate Source)

- Pre-Weaning Housing Effects on the Behavior and Physiological Measures of Pigs During the Sucking and Fattening Periods | Journal of Animal Science (Non-Compassionate Source)

- Early Social Experience of Piglets Affects Rate of Conflict Resolution with Strangers After Weaning | Conference: International Society for Applied Ethology (Non-Compassionate Source)

- Exercising Stallhoused Gestating Gilts: Effects on Lameness, the Musculo-Skeletal System, Production, and Behavior | Journal of Animal Science (Non-Compassionate Source)

- Environmental Enrichment Influences Survival Rate and Enhances Exploration and Learning but Produces Variable Responses to the Radial Maze in Old Rats | Developmental Psychobiology (Non-Compassionate Source)

- How Good? Ethical Criteria for a ‘Good Life’ for Farm Animals | Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics (Non-Compassionate Source)

- Cognitive Enrichment Affects Behavioural Reactivity in Domestic Pigs | Applied Animal Behaviour Science (Non-Compassionate Source)

- Saving Animals: Multispecies Ecologies of Rescue and Care | Elan Abrell

- Consent | Merriam-Webster

- Animal-Informed Consent: Sled Dog Tours as Asymmetric Agential Events | Tourism Management (Non-Compassionate Source)

- Entangled Empathy | Lori Gruen

- Empathy for Animals: A Review of the Existing Literature | Curator: The Museum Journal

- When Animals Speak: Toward an Interspecies Democracy | Eva Meijer

- Disability Rights for Sanctuaries Zoom Event | VINE Sanctuary

- Why Keep a Dog and Bark Yourself? Making Choices for Non-Human Animals | Journal of Applied Philosophy

- The Animals’ Agenda | Marc Bekoff and Jessica Pierce

Non-Compassionate Source?

If a source includes the (Non-Compassionate Source) tag, it means that we do not endorse that particular source’s views about animals, even if some of their insights are valuable from a sanctuary perspective. See a more detailed explanation here.

Open Sanctuary Project Sources

A Guide to Fostering Farmed Animal Agency in Sanctuary Education

A Guide to Fostering Farmed Animal Agency in Sanctuary Education: Consent Handout

What Does “Non-Compassionate Source” Mean at The Open Sanctuary Project?

In-Person Sanctuary Educational Programming: What Are Your Options?

What Does it Mean for Each Sanctuary Resident to Be an Individual?

The Importance of Veterinary Care at Your Animal Sanctuary

Understanding Infectious Diseases

The Caregiver’s Guide to Developing Your Observation Skills

Fostering Critical Thinking at Your Animal Sanctuary

Fostering Empathy Towards Farmed Animals

Creating a Vaccination Program for Your Animal Sanctuary

Breaking the Mold: How Animal-Centered Design Can Transform Sanctuaries