Veterinary Review Initiative

This resource has been reviewed for accuracy and clarity by a qualified Doctor of Veterinary Medicine with farmed animalA species or specific breed of animal that is raised by humans for the use of their bodies or what comes from their bodies. sanctuary experience as of September 2024.

Check out more information on our Veterinary Review Initiative here!

This Resource Is Not A Substitute For Veterinary Involvement!

In this resource, we’ll discuss how an uncomplicated delivery should typically progress and will also discuss some of the complications that may arise and how your veterinarian may recommend you proceed. However, this resource is merely informative and is not meant to be a substitute for veterinary involvement. Please always defer to your veterinarian for specific advice and contact them immediately if you have concerns about one of your residents.

In Part One of this series, we discussed important care considerations for pregnant sheep and goats. If you have not already checked out that resource, please do. Proper care during pregnancy can help reduce the risk of numerous complications. In addition to the topics discussed in that resource, another important part of caring for pregnant sheep or goats is monitoring the labor and delivery process and knowing when you should call your veterinarian for assistance. Monitoring the process will help ensure complications are detected and addressed as soon as possible. However, it’s important to do this without stressing the individual. While some sheep and goats may not mind human presence while they are in labor, others might not feel safe delivering their baby/babies with folks around. Be sure to give the individual space while still finding a way to check in to see how she is doing.

Technology Can Come In Handy

If you can, it might be helpful to install a camera that allows sanctuary personnel to check in on the individual via their phone or other device. This can make it easier to monitor how she is doing without causing her undue stress if she doesn’t appreciate your presence. Additionally, if you find yourself in a situation where you need to monitor her overnight, this can make the process a little bit easier.

Uncomplicated Delivery

Ideally, the mother will deliver her baby/babies without needing any assistance from you. If you have not witnessed the lambing/kidding process and are unfamiliar with how it progresses, it can make it very difficult to know if and when you should intervene. While you certainly want to be prepared to jump in and help if she needs it, remember that intervening when her labor is progressing normally can cause issues. Up next, we’ll talk about the stages of parturition and how things should typically progress so you have a basic understanding of the process.

Stage One: Preparation

During this stage, the mother’s body is preparing for delivery. The individual will experience rhythmic contractions, the baby/babies will be positioned for delivery, and her cervix will dilate. She may appear uncomfortable and may frequently move between lying down and standing up. You may also notice a mucous discharge coming from her vulva. Contractions will become stronger and more frequent as she nears stage two.

Stage Two: Delivery Of The Lamb Or Kid

This stage begins with the appearance of the water bag, which will look like a large bubble coming out of the vulva. This should rupture, releasing amniotic fluid, and then you should start seeing the baby. It typically takes an hour or less for the baby (or first baby, if there are multiple) to be delivered following the rupture of the water bag and the start of strong contractions. Individuals may choose to stand or lie on their side for this stage. Some individuals may not mind one or two humans being present (so long as they are quiet and calm), but others may, which can halt their progress. While monitoring is very important during this stage, be sure to do so from afar if that is what they need.

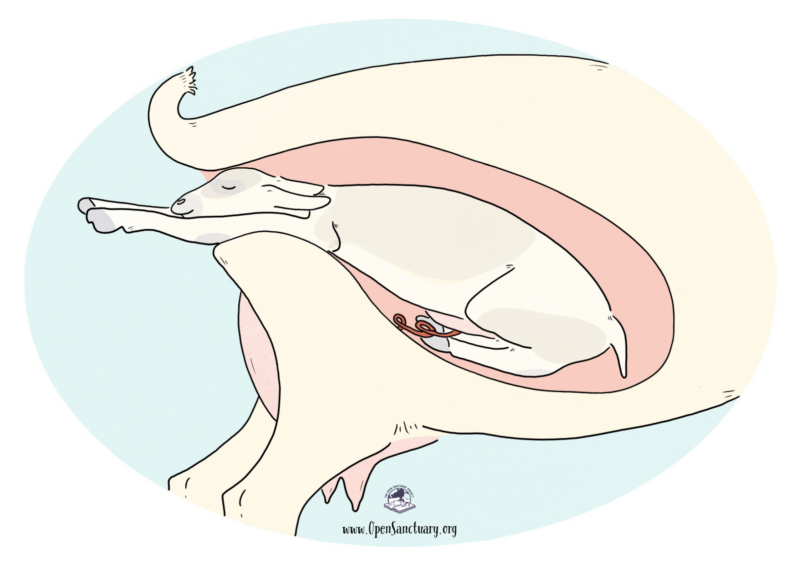

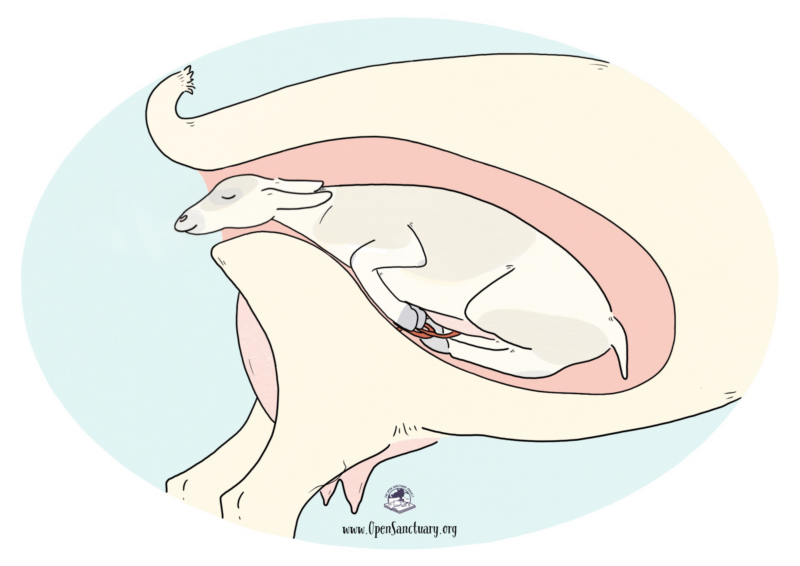

The normal presentation for a lamb and kidA young goat during delivery is front feet first (with the soles of their hooves facing down) and their head resting on their front legs (their nose should be pointing forward toward their front feet). The crown of the baby’s head will be aligned with the mother’s spine. This presentation is sometimes called the “dive” position. Once you see their front feet, it typically takes less than 30-45 minutes for the baby to be delivered.

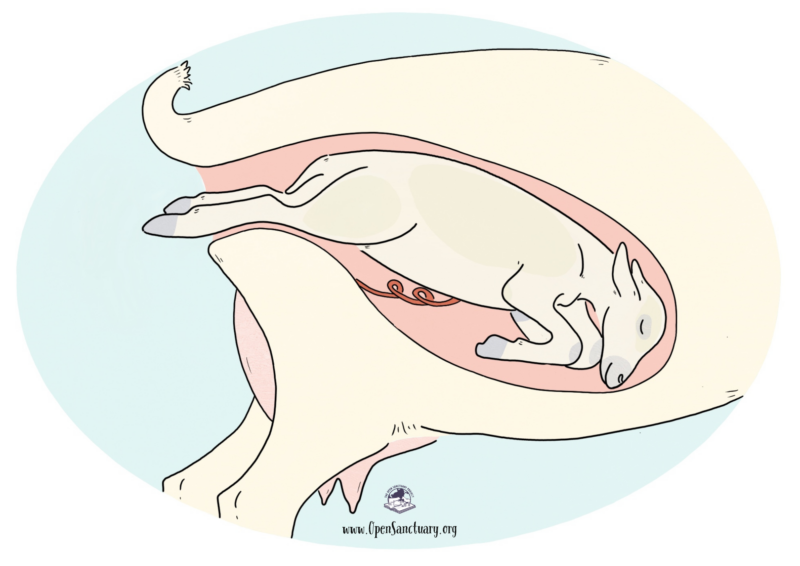

Though less common and a bit riskier, some babies may be delivered backward, with their back feet coming out first (with the sole of the hooves face up). This is different from a true breech position. Because this presentation carries additional risk, your veterinarian may advise you to assist. We’ll discuss both backward and breech positions more below.

If the mother is carrying multiple babies, which is not uncommon, they will usually be delivered within 30 minutes of each other. Following the birth of the first baby, the process will repeat with the rupture of the water bag, followed by the delivery of the next baby.

Stage Three: Delivery Of The Placenta

The final stage is the delivery of the placenta, which usually occurs within an hour or two of the delivery of the last baby (though it can take longer than this without being cause for concern – we’ll talk more about failure to deliver the placenta later in the resource). If she gave birth to multiple babies, there will be one placenta per baby. You should allow her to deliver the placenta on her own – do not attempt to pull it to assist her, as this can cause serious complications. Following delivery of the placenta, it’s best to remove it rather than allowing the mother to eat it (which is a normal instinct) to prevent possible disease spread.

Dystocia (Difficult Birth)

Above, we provided a general timeline for an uncomplicated birth. While the amount of time it takes a sheep or goat to progress through the different stages of parturition will vary from individual to individual, taking longer than the timeframes mentioned above could be a sign of trouble. Intervening in the labor process, while sometimes necessary to save the mother and/or baby’s life, does increase the risk of infection and other issues, so you only want to assist when necessary. As always, your veterinarian will be best able to advise you on how to proceed. Remember that in order to prevent exposure to infections that can cause birth complications and abortions, folks who are or may be pregnant should not come into close contact with residents who are in labor or have recently given birth.

There are various reasons why a mother may have trouble delivering her baby/babies. Common causes of dystocia include:

- Failure of the cervix to dilate (“ringwomb”) or failure to dilate fully

- Babies that are too big for the mother to deliver without assistance (“tight birth”)

- Malpresentation (baby is not positioned correctly to facilitate passage through the birth canal)

Dystocia may happen more often in young, first-time mothers, as well as older mothers and those carrying multiple babies. While we encourage folks to contact their veterinarian any time they have a concern, be sure to reach out to your veterinarian if you observe the following:

- The mother has been in distress for two hours but the water bag has not ruptured yet.

- The water bag has been hanging out of the vulva for 30 minutes or more, but the mother is not showing any signs of straining/pushing.

- The water bag has broken and the individual has been having strong contractions (straining) for 45-60 minutes, but the baby has not started to emerge.

- The mother was having active contractions, but they have now ceased.

- The baby is not in the typical “dive” position – we’ll talk more about abnormal presentations below (while back feet first is usually considered normal, if you are not experienced in the lambing/kidding process, a call to your veterinarian is wise since this can be a riskier presentation).

- The mother appears lethargic or significantly distressed at any point.

Depending on the situation, your veterinarian may talk you through gathering more information to help them determine what is going on and how to proceed. This may include asking you to check if the individual’s cervix is dilated and determining the position the baby is in. Before conducting an internal evaluation, it is imperative that you do the following:

- Clean the individual’s vulva and surrounding area with a mild disinfectant, as recommended by your veterinarian

- Remove any jewelry from your hands/arms, and make sure your fingernails are trimmed

- Put on obstetrical gloves

- Lubricate gloved hands/arms with a copious amount of lubricant

Checking The Cervix For Dilation

Depending on how things are (or are not) progressing, your veterinarian may ask you to check if the mother’s cervix is dilated. To do this, you will follow the steps above regarding cleaning, gloves, and lubricant, and will need to have the individual safely restrained before gently inserting your fingers into her vagina. If you meet a firm barrier, the cervix is closed. Your veterinarian may instruct you to give her more time to dilate, they may suggest administering oxytocin, or they may urge you to send her to the hospital for a cesarean. In some cases, the cervix may be soft and partially dilated. You can relay information about how dilated the cervix is by bringing your fingers and thumb into a cone shape and gauging how far into the cervix you can go (be gentle). Again, depending on the specific situation, your veterinarian will instruct you regarding next steps.

Checking The Presentation Of The Baby

If the baby has started to come out but seems to be stuck, or if your veterinarian had you check the mother’s cervix, and you determined that she is dilated but things aren’t progressing as they should, you may be instructed to check the presentation of the baby (what position they’re in). Knowing whether they are in a normal position or not will help determine the next steps. Remember, in a normal presentation, the baby’s front feet and head will come out first in a dive position. Backwards (with back feet coming out first) is also usually considered normal, but can be riskier.

Remember That Twins, Triplets, Etc. Are Possible

When determining the position of the baby, keep in mind that a mother may be carrying multiple babies. Sometimes, babies try to come out at the same time (simultaneous presentation), so you’ll need to make sure that what you are seeing (or feeling) in terms of head and legs belong to the same baby.

If the baby is in an abnormal position, knowing the exact presentation is critical and will dictate the next steps. If the baby has started to come out, you may be able to tell what presentation they are in just by looking at them, but often you will need to gently insert your fingers/hand into the mother’s vagina to determine the position and to confirm that you are not dealing with two babies trying to come out at once (again, following the guidelines above and any additional instructions from your veterinarian). We’ll talk more about different positions they may be in and how to potentially assist next.

Get Familiar With Lamb And Kid Anatomy!

Performing an internal evaluation to determine the position the baby is in is easier said than done. You need to rely on your sense of touch and your understanding of lamb and kid anatomy to try to picture what you are feeling. If you have never done this before, you may (understandably) be feeling a bit stressed and overwhelmed by the situation! To help set yourself up for success, take some time in advance to really get to know what the different parts of a lamb and kid feel like. Think about the different presentations described in this resource and what that would feel like during an internal evaluation. For example, with a normal presentation, you would expect to feel their front feet and face first. What would that feel like? If you only come across legs, how will you determine if you are feeling the front or back legs? (Hint: Think about how the first two joints of the leg differ between the front and back legs. On the front legs, both the fetlock and carpus bend in the same direction, whereas on the back leg, the fetlock and the hock1: the tarsal joint or region in the hind limb of a digitigrade quadruped (such as the horse) corresponding to the human ankle but elevated and bending backward 2: a joint of a fowl's leg that corresponds to the hock of a quadruped bend in opposite directions.) While reading about the different presentations is an important part of learning, don’t forget to seriously consider what those presentations will feel like so you can recognize them during an internal evaluation!

Assisting With Deliveries

Once you have relayed the necessary information to your veterinarian, they will instruct you on how to proceed, which may entail attempting to assist with the delivery process. Please note that there are many factors your veterinarian will consider when determining next steps. This includes but is not limited to your experience/comfort level, how the mother is behaving, how long she has been in labor, her health leading up to parturition, the presentation of the baby/babies, and how far you are from the nearest veterinary hospital capable of performing a cesarean. Always defer to your veterinarian for specific guidance, but below we’ll talk generally about some of the complications that may arise and how your veterinarian may recommend you respond. In some cases, they may advise you to use an obstetrical leg snare or lamb/kid puller, but these must be used carefully! We recommend learning how to use these before dealing with a difficult birth.

Work With The Mother, Not Against Her

If you do need to assist with the delivery, keep in mind that the mother will be having contractions and will (often) be trying to push the baby out. Pay attention to her contractions and work with them. If you need to push the baby back into her uterus to reposition them, do so in between contractions. Similarly, if you need to help pull the baby out, coordinate this motion with a contraction.

Tight Birth

If the baby is in the normal dive position but the process does not appear to be progressing properly, you may be dealing with a tight birth (alternatively, you may be dealing with an elbow lock, described more below). The baby may be too big for the mother because the father is much bigger than the mother, or the baby may be too big due to overfeeding the mother during pregnancy. Alternatively (or additionally), the mother may have a small pelvic opening. Depending on the situation, your veterinarian may talk you through trying to assist with delivery. If the mother is having trouble passing the baby’s head, you may be instructed to use a generous amount of lubricant and gentle pressure to help stretch the skin of the vulva over the baby’s head. In other cases, you may be instructed to use gentle traction to help pull the baby out by holding onto their legs and pulling in a downward arch toward the mother’s hocks. Remember, in some cases, the baby may be too large to be delivered vaginally, even with assistance, and a C-section will be necessary.

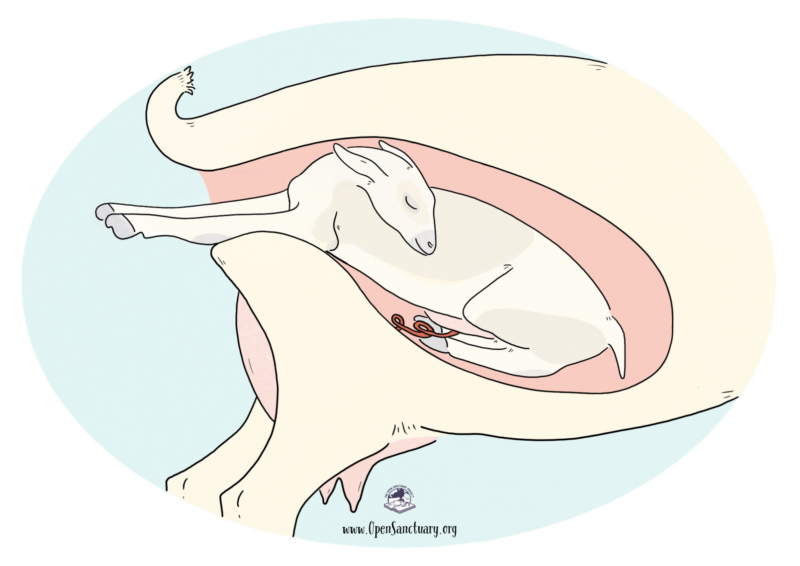

Backward Presentation

While this is technically a normal presentation, your veterinarian may recommend assisting to avoid complications for the baby. In this position, the umbilical cord will break before the baby’s head is out of the mother, necessitating a quick delivery to avoid the baby taking their first breath while still surrounded by amniotic fluid, which would result in aspiration. If the delivery takes too long, the baby can drown. Never try to reposition a backward-presenting baby so that they are in the typical dive position. Instead, your veterinarian may guide you through gently pulling the baby out by the hind legs. When assisting with a backward delivery, you typically want to pull straight back until the baby’s pelvis is out of the vulva and then pull downward until the rest of the baby is out.

Malpresentations

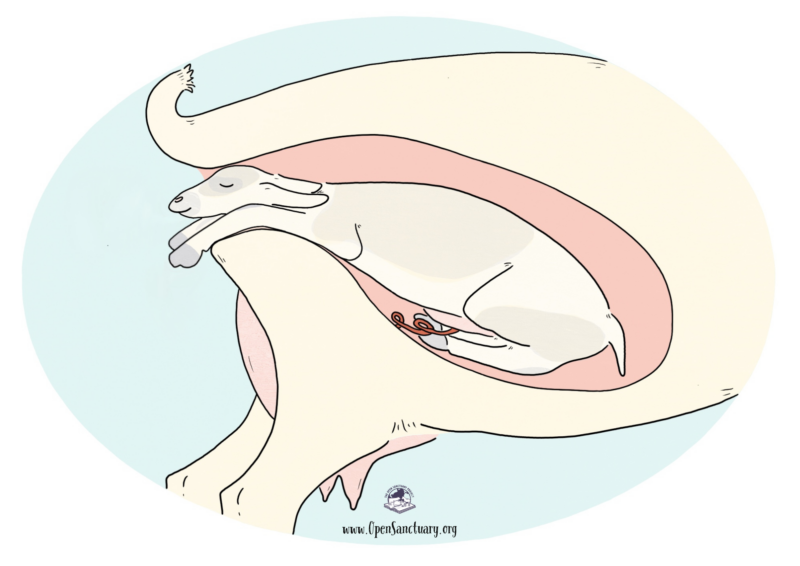

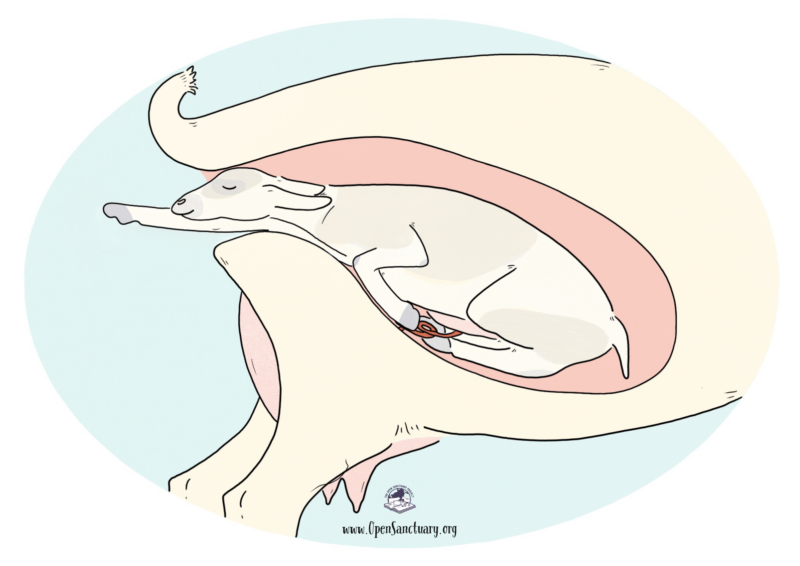

If you’ve identified that the baby is in an abnormal position, your veterinarian may instruct you to reposition the baby, depending on the position they’re in. The birth canal is too tight to allow for repositioning of the baby, so this entails gently pushing them back into the mother’s uterus and then repositioning them. Before assisting be sure to follow the guidance above regarding cleaning, gloves, and lubricant. Below, we’ll discuss some of the common malpresentations and how to reposition them, but be sure to defer to your veterinarian for specific guidance!

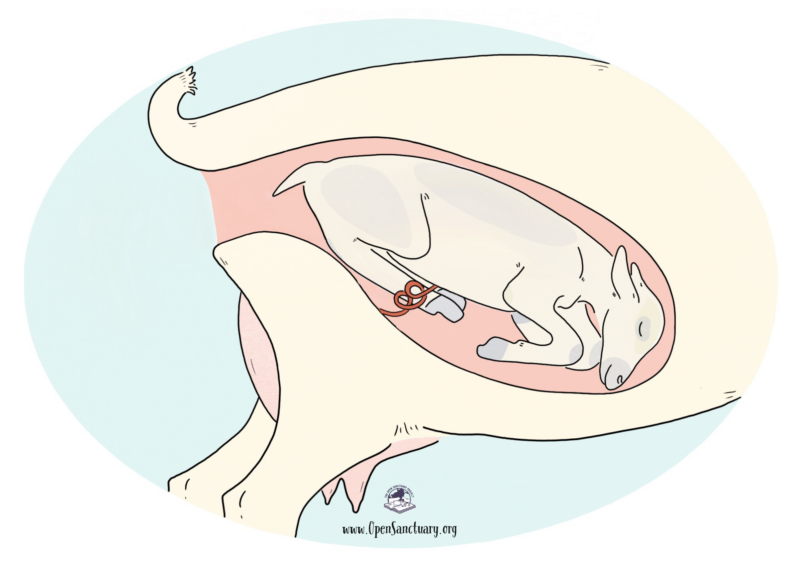

Elbow lock – With this presentation, the baby will start to come out in what looks like a normal presentation, with the tip of the front feet and nose coming out first, but their elbows are locked behind the mother’s pelvis, causing them to become stuck. Repositioning an elbow lock presentation typically involves gently pushing the baby’s head back into the birth canal and then using gentle traction to pull the front legs forward, one at a time.

One leg back – With this presentation, rather than having both front legs extended forward, one is tucked under the baby. If the baby is partially out, you may just see one foot or you may see one foot/leg and their nose/face/head. If they have not yet started to come out and you are determining presentation via an internal evaluation, you will feel one foot and their nose pointed forward, but the other leg will not be immediately felt – sometimes it is bent at the carpus (“knee”) and other times it is extended under them. Repositioning typically involves locating the shoulder of the leg that is tucked back and then working your way down the leg until you find the foot. The leg is then extended forward, keeping the hoof cupped in your hand to protect the uterus from damage. If the baby’s head has already started to come out, it is usually necessary to gently push their head back a bit so there is room to reposition their leg.

Both legs back – This presentation is similar to the one above, but instead of just one leg being tucked under them, both are. During an internal evaluation, you will feel their nose/face, but their legs will not be immediately felt. If the baby starts to come out in this presentation, only their face/head will emerge. Repositioning is similar to what is described above and typically involves extending one leg at a time.

“Swollen Head” Presentation

If the baby’s head is delivered and one or both legs are back, causing them to become stuck, their head may begin to swell if the issue is not addressed quickly (which may happen if someone goes into labor unexpectedly and you are not there to monitor their progress). If you come across a mother and baby in this situation, it can be quite alarming. Not only will the baby’s head swell, but their tongue may also be hanging out, and they may appear dead. However, they can survive for hours with just their head coming out, so be sure to check if they are alive before jumping to any conclusions, and contact your veterinarian for guidance. Repositioning to extend the legs can be difficult if the head is swollen, so veterinary involvement may be required.

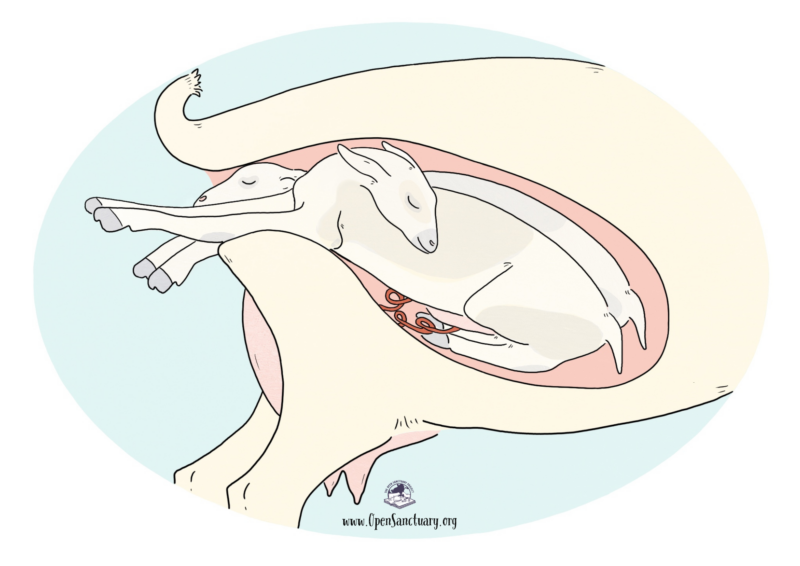

Head back – With this presentation, the front legs are extended forward, but the head is turned (so the nose is facing away from the birth canal rather than being positioned above the front legs). Repositioning typically involves gently pushing the baby back into the uterus and then turning the head into the correct position. It can be tricky finding the head, and once you do, you need to make sure the head and front legs belong to the same baby!

Breech – With this presentation, the baby is positioned tail first. Whereas in a backward presentation, their back legs will come out first, in a true breech position, their back legs will be tucked under them, with their hooves pointed toward the front of their body (and away from the birth canal). During an internal evaluation, you will feel their bum and tail. Because a breech presentation can be tricky to deal with, it may be best to have your veterinarian come out to assist (or to bring the mother to them), but, if the situation is urgent, your veterinarian may need to talk you through repositioning and assisting with delivery. When repositioning a breech presentation, the goal is typically to get the baby into the normal backward position with their back legs extended behind them and coming out first. This involves finding their back feet, cupping their hooves in your hand to protect the uterus, and extending the legs backward (toward the birth canal). Once they are properly positioned, you will likely be instructed to deliver the baby quickly (but carefully) since the umbilical cord will break before their head is delivered.

Simultaneous births – With this presentation, the mother is carrying multiple babies, and more than one is attempting to be delivered at the same time. This may look and/or feel like a normal presentation with two front legs and a head in the birth canal, but one or both legs actually belong to a different baby. In some cases, you may actually feel or see three or four legs. Repositioning typically begins with determining which legs/head belong to which baby and carefully untangling them (if necessary). Next, it’s important to determine which baby should be delivered first based on the position they’re in (e.g., if you can find both front legs and the head of Baby A and only the legs of Baby B, Baby A should be delivered first after Baby B has been gently pushed back to make more room). In some cases, one or both babies may need to be repositioned before being delivered. After the first baby is delivered, your veterinarian may instruct you to wait to see if the mother can deliver the second baby on her own, but other times they may instruct you to assist in delivering them right away.

After assisting with the delivery of a lamb or kid, place them in front of their mother so she can begin cleaning them. Be sure to connect with your veterinarian about having the mother and baby assessed to make sure all is well following a difficult birth. We’ll talk more about the care the mother and baby require below.

Check For Multiple Babies

We’ve mentioned this throughout this resource, but keep in mind that it’s possible (and sometimes very likely!) that a mother is carrying multiple babies. After the delivery of one baby, watch for signs she may be delivering a second (or more) baby. In some cases, your veterinarian may advise that you conduct an internal evaluation to check for the presence of another baby.

If you are having difficulty repositioning the baby or otherwise assisting with the delivery, be sure to consult with your veterinarian for further guidance. If they are unable to come out to assist, you will need to carefully transport the mother to get her the help she needs. In some cases, you may be able to drive to your veterinarian’s clinic or home, but other times you may need to drive to the nearest large animal hospital (remember, make a plan ahead of time so you are not scrambling to figure out where to go or who to call).

Post-Delivery Care For Mother And Baby/Babies

Ideally, all new mothers and their babies should be evaluated by your veterinarian within a few days of delivery, but for those who experienced complications, more immediate assessment is warranted. Be sure to consult with your veterinarian following a difficult birth so they can assess everyone and make specific recommendations for their care. In this section, we’ll talk generally about caring for a sheep or goat and her baby/babies in the period immediately following birth.

After delivery, the first 18 hours are the most critical. With rare exceptions, you’ll want to keep the mother and baby/babies together and separate from other sheep and goats during this time. Make sure they’re in a clean, dry area that can keep the baby warm and is draft-free while still allowing for proper ventilation. This may require the addition of a safe heat source, but this must be done carefully to ensure the mother does not overheat (and you also have to keep fire safety in mind).

Under ideal circumstances, the mother will tend to her baby/babies after they are delivered and neither they nor she will require much assistance from you (though there will still be a few things you need to do). However, this is not always the case, particularly following a difficult birth or if the mother’s needs were not met during pregnancy. Therefore, close observation is imperative during the period immediately following delivery.

Do Not Separate The Mother And Baby Unless Absolutely Necessary

If the mother or baby requires hospitalization, be sure to send them together whenever possible. This is something you will need to arrange with the hospital to ensure they can accommodate everyone. In some instances, a mother or baby may require such intensive care that it is not possible to keep them together, but we always recommend keeping them together when possible.

Caring For Newborn Lambs And Kids

It’s crucial that you ensure the baby is breathing immediately after being born. If they are not, you need to take immediate steps to assist them. You may need to clear mucus from their mouth and nose, and this can be done with a piece of gauze or cloth, or you can use a bulb syringe or nasal aspirator to remove mucus from their nostrils. If the baby still is not breathing, you can use a lamb/kid resuscitator to pump oxygen to the lungs. Alternatively, you may need to hold the baby upside down to try to clear their airways. To stimulate breathing, you can try gently rubbing their chest, tickling their nose with a soft piece of straw, or blowing air into their nose (do not put your mouth on a wet baby, as this could expose you to disease). Be aware that in rare instances, the baby may be born with the water bag intact (yet another reason close monitoring is imperative), and this will need to be ruptured and removed immediately to allow them to breathe.

The mother should show interest in her baby/babies and almost immediately start cleaning them (by licking them). It’s best to let her do this without intervening, as it is an important part of the bonding process. If she does not start cleaning them on her own, place the baby/babies by her head, which will hopefully encourage her to start cleaning them. If the mother can’t or won’t clean her baby/babies, you’ll need to clean and dry them off yourself. You use clean, dry towels to gently dry them off and, if needed, can then use a quiet blow dryer on the low setting to help finish the drying process. Unless absolutely necessary, do not remove the babies to clean and dry them – instead do this with the mother present, continuing to try to encourage her to clean them.

Even if the mother is diligent about cleaning her baby, you will need to step in to tend to their umbilicus (naval). Unless there is an issue, you can typically wait until the mother is done cleaning the baby to do this. If the umbilical cord is very long and there is a chance the baby may step on it when trying to walk (which could tear it and cause bleeding), your veterinarian may instruct you to use an umbilical clamp and then trim it to a length of two inches using clean and disinfected tissue scissors. Regardless of whether the umbilical cord needs to be trimmed or not, you should dip the umbilicus and attached cord in a 7% povidone-iodine solution or 2% chlorhexidine solution (continued naval care is imperative and is discussed in our lamb and kid care resources which are linked below).

Check In With Your Veterinarian About Selenium

If your sanctuary is in a selenium-deficient area, your veterinarian may recommend administering selenium (Bo-Se) to newborns. Be sure to check in with them about whether or not this is advised because giving it unnecessarily can result in toxicity.

It’s a good idea to check the mother’s udders for colostrum (the first milk she produces for her baby, which contains protective immunoglobulins and important nutrients and growth hormones). Removing the wax plug from her teats may also make it easier for the baby to nurse. A healthy baby should stand and start nursing within an hour of being born, though they will be a bit wobbly at first. In some cases, they may need assistance finding the teat (especially if you did not remove long hair or wool from the surrounding area). Watch to make sure they latch on (and stay latched) and help them if needed.

Ensuring the baby receives enough colostrum is crucial! There is only about a 24-hour window for the lamb/kid’s intestinal lining to be able to absorb the colostrum’s antibodies (which will give the baby passive immunity). The most effective absorption time is during the first 4-6 hours after birth, with an exponential loss in effectiveness as time goes on. Typically a baby needs 10-20% of their body weight in colostrum, ideally spread out between multiple feedings over the first 12 hours with the first feeding occurring within the first 2 hours after birth. If the baby is nursing on their own and the mother is producing enough colostrum, they should get all they need, but you should watch to make sure they are nursing regularly. After nursing, you should be able to feel that the baby’s abdomen is full of milk (versus sunken in).

You will need to intervene if the baby is too weak to nurse, if the mother is not producing enough colostrum, or if the mother will not allow the baby to nurse. If the baby is unable to stand within an hour of birth or if they appear lethargic or are showing other signs of concern, contact your veterinarian immediately. They can assess the baby and provide specific guidance, but one thing is certain – they must receive colostrum. In some cases, you may be able to hold them up near their mother’s teat to encourage them to nurse on their own. However, if the baby is too weak to nurse or is unable to suckle, they will need to be tube-fed colostrum. This should only be attempted by your veterinarian or an experienced caregiverSomeone who provides daily care, specifically for animal residents at an animal sanctuary, shelter, or rescue. (under your veterinarian’s guidance). Improper tubing can result in aspiration and even death. If the mother is producing enough colostrum, you can milk her and use this to feed the baby. Be sure to follow your veterinarian’s instructions regarding how much and how often to feed to ensure they get all the colostrum they need.

If the mother is not producing enough colostrum (which we’ll talk about more below), you will need to supplement the baby with another colostrum source (such as thawed frozen colostrum or a colostrum replacer). If the baby is eager to nurse, you can bottle-feed them, otherwise they will need to be tube-fed. If the mother won’t let the baby nurse, be sure to consult with your veterinarian. In some cases, it may be that nursing is causing the mother pain, but other times she may be rejecting the baby for another reason. Depending on the situation, you may need to bottle-feed the baby going forward.

There’s much more to caring for lambs and kids! To learn more, check out our resources Care Recommendations For Lambs and Care Recommendations For Goat Kids.

Caring For The New Mother After Delivery

In addition to monitoring the baby/babies closely, you’ll also need to monitor the mother closely. If you needed to perform an internal evaluation or had to assist with the delivery, be sure to check in with your veterinarian about follow-up care to reduce the risk of complications – this typically includes an antibiotic treatment for the mother, but they may recommend additional treatments for the mother or baby based on the specifics of the situation.

Just as certain conditions commonly affect pregnant sheep and goats, some conditions tend to affect them in the period shortly after parturition. These include retained placenta, prolapsed uterus, and agalactia. It’s important to familiarize yourself with these conditions so you can watch closely for signs an individual may be affected.

Retained Placenta

As explained above, stage three of parturition is delivery of the placenta, and this should occur within a few hours of the delivery of the last baby, though it can take up to six hours without being cause for concern (so long as she is not showing other signs of concern). The placenta is considered retained If not delivered within 12-18 hours, and you should contact your veterinarian for guidance. They may recommend administering oxytocin or prostaglandins to encourage her to pass the placenta. They may also recommend additional treatments, including antibiotics to prevent uterine infection.

Prolapsed Uterus

Uterine prolapsethe falling down or slipping of a body part from its usual position or relations, in which the uterus is turned inside out and comes out through the vulva is a serious, life-threatening condition, and your veterinarian should be contacted immediately. This may occur immediately following the delivery of their baby, especially following a difficult birth, but can also occur in the first few days following parturition. Unlike a prolapsed vagina, in which the tissue is smooth, a prolapsed uterus is covered in caruncles, which look like oval lumps. The amount of tissue prolapsed will vary, but in cases of a complete prolapse, the tissue will hang down past the hocks. While waiting for veterinary assistance, take steps to protect the prolapsed tissue, such as by carefully placing a sheet under her to protect the uterus from damage.

Agalactia

Agalactia is the term used to describe an absence of milk from an individual who should be lactating. This may be due to a failure to produce milk or a delay in the milk let-down reflex. There are numerous causes for this condition, including hormones, poor nutrition, a difficult birth, stress, and diseases such as mastitis, ovine progressive pneumonia (OPP), or caprine arthritis encephalitis (CAE). Depending on the cause, your veterinarian may recommend administering oxytocin to try to encourage milk letdown. However, if the individual is not producing milk, you will need to bottle feed the baby (you can read more about bottle feeding in our lamb and kid resources).

Please remember, if you have any concerns at any point before, during, or after labor and delivery, contact your veterinarian for guidance! They will be your best resource when determining how to proceed.

To learn more about caring for sheep and goats during lactation, check out Part Three of this series!

SOURCES:

Retained Fetal Membranes in Does and Ewes | Merck Veterinary Manual

Veterinary Viewpoints: Recommendations For A Successful Lambing And Kidding Season | Oklahoma State University (Non-Compassionate Source)

Parturition – Part III | MD Small Ruminant (Non-Compassionate Source)

Assisting Ewes With Difficult Births (Dystocia) | Alberta Lamb Producers (Non-Compassionate Source)

The Lambing Process | Sheep 201 (Non-Compassionate Source)

Care Of The Newborn Lamb | Ontario Ministry Of Agriculture, Food And Agribusiness And Ministry Of Rural Affairs (Non-Compassionate Source)

Non-Compassionate Source?

If a source includes the (Non-Compassionate Source) tag, it means that we do not endorse that particular source’s views about animals, even if some of their insights are valuable from a care perspective. See a more detailed explanation here.