HPAI Detected In DomesticatedAdapted over time (as by selective breeding) from a wild or natural state to life in close association with and to the benefit of humans Ruminants In March 2024

On March 20, 2024, The Minnesota Board Of Animal Health (MBAH) announced the first detection of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) in a domesticated ruminant in the U.S. after a goat kidA young goat in Stevens County tested positive. Soon after, HPAI was detected in cowsWhile "cows" can be defined to refer exclusively to female cattle, at The Open Sanctuary Project we refer to domesticated cattle of all ages and sexes as "cows." at dairies in Texas and Kansas and has since been detected in cows in additional states. This is a developing situation. For more information about HPAI in domesticated ruminants, check out our FAQ here.

Please note that the following resource was written before HPAI had been detected in domesticated ruminants. The information contained within was written specifically with domesticated birds, and more specifically, farmed bird species, in mind. While it is too early to know how the current situation in domesticated ruminants will unfold, as of April 11, 2024, the governmental response to these detections has been very different from the current response to detections in farmed bird species. Whereas a positive detection in a farmed bird will result in the compulsory killing of all domesticated birds on the premise, this has not been the case in domesticated ruminants. We’ll be sure to share more information as we have it.

Resource Goals

- Gaining a general understanding of how federal law (both statutory and administrative) in the United States operates around detections and responses to diseases like highly pathogenic avian influenza (which will be referred to as “HPAI”);

- Gaining a general understanding of the role of state law, and how it intertwines with federal law when it comes to responses to detections of HPAI;

- Learning about lawsuits for injunctive relief and lawsuits for damages, and the logistical, and legal barriers, and unintended consequences that may accompany them;

- And gaining a better understanding of why careful biosecurity and recordkeeping procedures are the primary and best measures that you can take when it comes to protecting your avian residents from both the HPAI virus, and associated control measures.

Reminder: We Aren’t Your Lawyer!

The Open Sanctuary Project is not a law firm and this resource is not a substitute for the services of an attorney. Accordingly, you should not construe any of the information presented as legal advice that is suitable to meet your particular situation or needs. Please review our disclaimer if you haven’t yet.

Introduction

Content Warning

This resource will address HPAI control measures, which include the discussion of the mass killing of birds. However, in recognition of the highly stressful nature of the current outbreak situation for rescuers and sanctuaries, we will not include graphic images of birds suffering from the virus or of control measures.

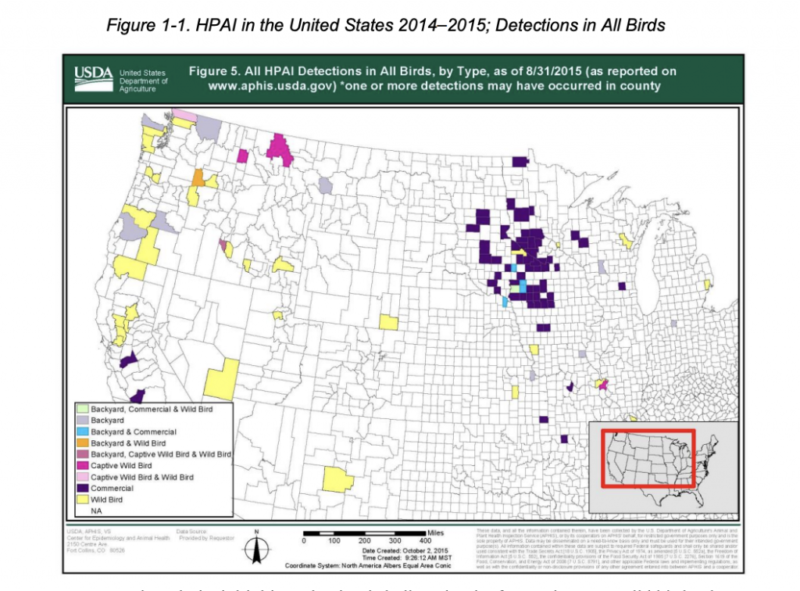

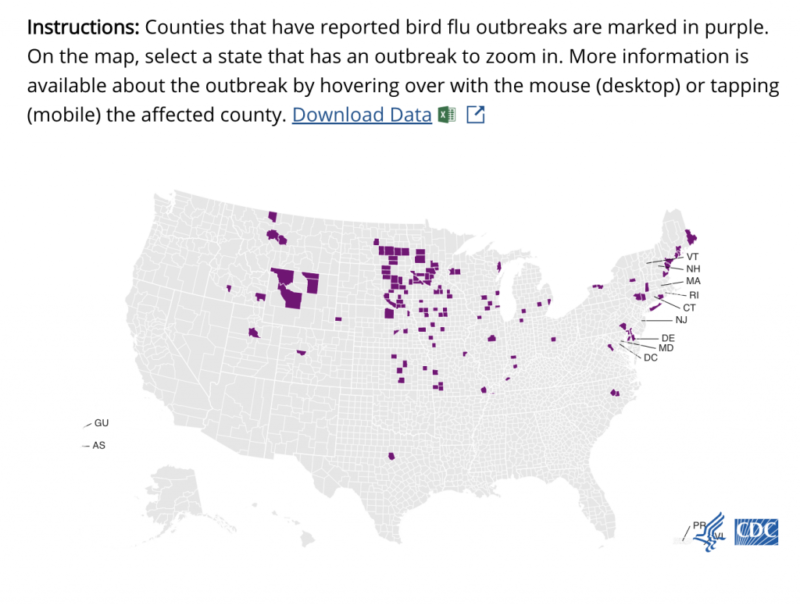

Detections of highly pathogenic avian influenza in domesticated birds continue to rise in more and more states across the U.S. For current numbers, please refer to the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (hereinafter “APHIS”) of the United States Department of Agriculture’s 2022 Detections of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza page, which makes announcements as the first finding in a new state is confirmed. Also please see this page, which documents findings by day, as well as the total number of birds affected thus far, breaking numbers down by commercial and “backyard” flocks. Let’s be very clear about what “being affected” means for birds in this context: It means that all the “affected” birds have been “depopulated,” a euphemism for being killed, in order to prevent the spread of the virus. The last major HPAI outbreak looked like this on a map:

While certain animal industrial agriculture publications attribute the current rate of detections of HPAI to much higher levels of surveillance, it seems clear that the current outbreak is well on its way to surpassing that of 2014-2015. As of this writing, the current outbreak of HPAI according to a map published by the Center for Disease Control, which includes only “backyard and commercial birds,” looks like this:

That grim fact brings us to what is particularly scary for sanctuaries and caregivers about HPAI: it is a “double-pronged” threat. First, there is the clear and present risk of your avian residents contracting HPAI through contact with wild birds, or through other indirect contact with the virus, which is a deadly risk. The second risk centers around what can happen if HPAI is detected in domesticated birds in your area. This second risk is also a potentially deadly risk, because it comes with the possibility of surveillance and testing of your avian residents, and if one tests positive for HPAI, the almost certain “depopulation” i.e. killing of all of your avian residents.

It has become painfully clear since this outbreak began that the HPAI virus does not discriminate. ZoosOrganizations where animals, either rescued, bought, borrowed, or bred, are kept, typically for the benefit of human visitor interest., backyard flocks, rehab facilities, commercial facilities, and sanctuaries alike can all be impacted by HPAI if they do not take protective measures with respect to their residents. It’s not a matter of how much you love your birds, or how good your care is generally – being a sanctuary makes no difference to the virus. In the wake of this very scary reality, many sanctuaries have questions as to what actions they can take to protect their avian residents. Let’s be very clear here: There is a great deal that you can do and control in the face of this risk, and that is your biosecurityMerck Veterinary Manual defines biosecurity as ”the implementation of measures that reduce the risk of the introduction and spread of disease agents [pathogens].” and recordkeeping. We cannot emphasize this enough.

How You Can Help Protect Your Residents

All risks to your avian residents of HPAI infection are directly related to the measures that YOU actively take to protect them from direct or indirect contact with:

1. Infected wild birds and other wildlife;

2. People who have been exposed to infected wild bird feces;

3. And contaminated fomitesObjects or materials that may become contaminated with an infectious agent and contribute to disease spread which include tools, vehicles, bedding, and food.

The best way to protect your flock from ALL aspects of the HPAI threat is always going to be taking proactive and strong defensive biosecurity measures, and administrative measures to document them!

We have resources to support you in this! You can educate yourself on HPAI, create implement and enforce a biosecurity plan and checklist at your sanctuary, and do careful daily recordkeeping using templates like these. The most important thing you can do right now is to take these measures, and it is absolutely critical to take them seriously.

When it comes to the “second prong” of the HPAI threat, the question of surveillance and control measures in areas where HPAI has been detected, unfortunately, we have fewer answers.

We have gotten repeated questions with regards to this “second prong,” some of which may be potentially upsetting, so please be forewarned. These questions include:

- What happens if HPAI is in my region? Is my sanctuary subject to surveillance?

- What happens if HPAI is detected in my avian residents? Will all my avian residents be killed?

- Do I get a say in how my birds are killed, if my avian residents must be “depopulated?”

Again, we can’t give simple answers to many of these. Our goal in this resource is to offer the answers that we do have, and to help you get a better understanding of the complexities around these questions, and why they’re so hard to answer. We know that it is deeply frustrating that even once you have taken all biosecurity and administrative measures possible to protect your residents, you may still have to deal with the question of being potentially subjected to control measures. The good news we can give you is that, while even the best biosecurity and recordkeeping may not prevent you from having to deal with HPAI surveillance, taking these measures may help you and your residents significantly when it comes to further control measures if you do find yourself faced with them.

Sanctuary and caregiverSomeone who provides daily care, specifically for animal residents at an animal sanctuary, shelter, or rescue. friends, you may be asking, “WHY are there no clear answers to these questions?” There are a number of reasons, but first and foremost, it is because HPAI control measures are administered jointly: both federally by the United States Department of Agriculture (hereinafter “USDAThe United States Department of Agriculture, a government department that oversees agriculture and farmed animals.”), and by the state in which the detection occurs. This quickly becomes complicated because reporting requirements and responses may differ state-by-state to some extent. For this, we can thank federalism, to be further explained below.

This is why, much of the time, the best answer we can offer you is a qualified “lawyer answer”: the notorious response: “It depends.” We wish we could offer straightforward, concrete guidance here. But there are many reasons why we cannot, and it’s important for you to understand why.

When it comes to disease responses in farmed animalsA species or specific breed of animal that is raised by humans for the use of their bodies or what comes from their bodies., things get really tricky, really quickly. But to make it understandable, let’s start by considering federal law around HPAI, so you can get a better understanding of what kind of response powers the federal government has with regards to outbreaks like HPAI.

This Is Just A Primer!

A comprehensive consideration of the law around animal agricultureThe human production and use of animals in order to produce animal products, typically for profit. in the United States is beyond the scope of this resource. Our aim is solely to give sanctuaries a general idea of the interplay of powers of when it comes to both federal and state government responses to diseases like HPAI, and how those may play out into “control measures” that can impact your sanctuary. Our hope is to offer guidance that can enable sanctuaries to understand the seriousness of both the HPAI threat to residents, as well as the control measures that may be faced.

The Question of Federalism

To get a sense of how federal and state laws relate to each other, let’s do a quick review of the United States Constitution. You might say, “Why? Yuck!” We have to talk about it because surprisingly, federalism comes up again and again when it comes to animal rescueAn organization that helps secure animals from dangerous or unacceptable situations. As organizations, rescues may or may not have dedicated permanent infrastructure for housing animals. and sanctuary concerns. So many issues tie into it, including questions about interstate transport, ear tagging, and what we’re talking about here, which is disease.

We promise to keep it as short and painless as possible! So what is “federalism?” In the U.S., it’s about the dynamic when state and federal laws dance with each other, and how this dance is often a power play. Simply put, federalism is the question of how simultaneous control of the same territory works when there is a larger controlling power (the federal government) and a smaller local power (the state government). As you might imagine, there are many dynamics. Under the U.S. Constitution, many powers are reserved for states when it comes to legislation. These powers include creating school systems, overseeing state courts, creating public safety systems, managing business and trade within the state, managing local governments, and more. These powers are referred to as “reserved powers.” However, federal powers can sometimes trump state powers!

The United States Congress’ power (or federal power) to regulate is generally controlled by what is commonly known as the “Commerce Clause”, which is complemented by the powers of the “Necessary and Proper Clause”. The “Commerce Clause” gives Congress the power to regulate “commerce” among the several states and the “Necessary and Proper Clause” provides that Congress shall have power to “make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof.”. You may already see how these broad terms can lead to tangles between state and federal regulations at times!

How does this relate to HPAI? When it comes to questions about industrial animal agriculture, there are many practices that involve the transport of animals across multiple states. Obviously, this includes transport regulations, things like ear tagging in some animals for traceability, as well as questions of disease. Interstate questions like these give the federal government power to regulate animal agriculture, and so there are many federal laws that deal with it. This is especially true when it comes to questions of disease. But there is also state-by-state legislation governing the same questions. So when we talk about control measures around HPAI, this interplay becomes important! So let’s start by briefly considering federal statutes and regulations:

A Look At Federal Law

Federal law is very complex. As mentioned above, there are a lot of statutes that impact farmed animals, from questions of transport, to regulations around how they are kept, and questions about the killing of animals. In general, what federal statutes tend to do is vest and delegate authority for these matters in administrative agencies that are “specialized” in these particular questions. The USDA is generally the main agency responsible, although believe it or not, sometimes agencies like the Department of Homeland Security can make appearances in this realm! The USDA then, based on the statutory authority given to it by Congress, will issue regulations under each statute, as well as provide additional guidance, and will also coordinate with the states. It also can delegate authority to the states themselves, sometimes by allowing them to generate their own regulatory programs that are “as good as or equal to” the standards that are set by the USDA. So even within the federal law dealing with these questions, there are layers to consider. And there are other external pressures and factors that come into play, like economics. So let’s briefly look at that so we understand the larger context of federal regulation.

HPAI And Economics

It is a harsh reality that the dominant culture views farmed animals, including chickens and other “poultry” as either consumable objects, or objects who generate consumable objects (i.e. eggs). It is therefore unsurprising that how these beings are treated under the law relates back to their “value” as it pertains to human consumption. When it comes to all regulations with respect to the lives of farmed animals, this is a common theme. It is then also not a shock that this holds true when it comes to how the government views and treats the question of disease in farmed animals. Generally, what the government will consider first is the question of human safety and welfare.

Questions related to that include the following: “Is this disease zoonotic (i.e. transmissible to humans)”? “If humans can catch it, who is most susceptible? Is it workers who deal with the animals in question, or is it consumers?” (In general, there is more concern expended on the latter than the former, as most workers involved in working with farmed animals tend to be low-paid and highly marginalized individuals.)

Finally, there is the related but overarching question of the almighty dollar. The following facts may be upsetting to some, but we have to share them because they play heavily into legal considerations around farmed animals: According to the North American Meat Institute, “the meat industry contributes approximately $894 billion in total to the U.S. economy, or just under 6 percent of total U.S. GDP and, through its production and distribution linkages, impacts firms in all 440 sectors of the U.S. economy, directly and indirectly providing 5.9 million jobs in the U.S.”

So economics plays a significant role when it comes to questions of diseases that impact farmed animals. If you have been following coverage of HPAI in the news, you probably have already heard questions like: “How will HPAI impact the income of poultry “producers”/exporters (i.e. the animal agriculture industry) when it comes to controlling it?” “When it comes to HPAI control measures, who will bear the burden of these costs?” “How do we minimize the impact to trade that an HPAI outbreak presents?” Probably one of the more upsetting questions asked is, “How will HPAI influence consumer prices of eggs and chicken meat?”

These will be questions we address further below. When it comes to the answers, HPAI has yet again exposed all of the biases that our culture holds when it comes to farmed animals. With all this said, let’s now look at the relevant laws that impact HPAI, keeping this strong cultural bias in mind:

The Animal Health Protection Act

When it comes to HPAI, the most relevant federal statute is the Animal Health Protection Act. The Congressional findings that preface this Act should make sense given what we discussed above regarding interstate commerce and the Commerce Clause. In short, Congress found that when it comes to “the prevention, detection, control, and eradication of diseases and pests of animals…regulation by the Secretary [of the USDA] and cooperation by the Secretary with foreign countries, States or other jurisdictions, or persons are necessary” to prevent and effectively regulate interstate and foreign commerce, and to protect the agriculture, environment, and the health and agriculture of people in the U.S.

But what does “disease” mean in this context? This statute will not give you the definition, but §8302(3) provides that “the term “disease” has the meaning given the term by the Secretary”. What this means is that the task of deciding how to define what diseases are regulable under this Act is a decision that is up to the discretion of the USDA. To that end, what has happened is that the USDA and APHIS have developed a list of “notifiable diseases and conditions” which can be found here. This list closely follows (but is not identical to) the World Organization for Animal Health’s (hereinafter “OIE”) list of notifiable terrestrial and aquatic animal diseases, which can be found here.

In the case that a veterinarian diagnoses or suspects a “notifiable disease or condition” that is on this list, they must report this to their USDA Veterinary Official and the relevant state Animal Health Official. At this point, USDA disease control and eradication measures kick in. What does that mean? Under the Animal Health Protection Act, among other powers, the USDA is authorized to “hold, seize, quarantineThe policy or space in which an individual is separately housed away from others as a preventative measure to protect other residents from potentially contagious health conditions, such as in the case of new residents or residents who may have been exposed to certain diseases., destroy, dispose of, or take other action” with respect to any animal, article, or means of conveyance that is moving or has been moved in interstate commerce, that “may carry, may have carried, or may have been affected with or exposed to any pest or disease of livestockAnother term for farmed animals; different regions of the world specify different species of farmed animals as “livestock”.”. Again, this day-to-day power of the USDA is based on the Commerce Clause, referenced above.

So why do we care about this as sanctuaries and caregivers, if we don’t happen to be moving animals interstate? Unfortunately, the Animal Health Protection Act doesn’t leave it at this! There is an additional federal regulation that kicks in when an “extraordinary emergency” occurs. The term “extraordinary emergency” isn’t defined by the statute, but the powers of the USDA in such situations are expanded significantly. And to be clear, the current HPAI outbreak is considered such an emergency.

The statute says that in the case that USDA determines that an extraordinary emergency exists that threatens the livestock of the U.S., then under §8306(b) of the Animal Health Protection Act, the USDA can “hold, seize, treat, apply other remedial actions to, destroy (including preventive slaughter), or otherwise dispose of any animal, article, facility, or means of conveyance” if it is determined to be necessary to prevent the dissemination of the disease. Further, in such a situation the USDA can also intervene when it comes to the travel of animals intrastate (or within a state.) This could mean that even transport from your sanctuary to the local vet could potentially fall under these powers.

And there’s more. This statute also provides for the power to do warrantless inspections under §8307(b), which provides that the USDA can stop and inspect, without a warrant, any person or means of conveyance carrying any animal in interstate commerce that might be regulated, OR any animal in intrastate commerce that might be quarantined under the statute!

Simply put, what all this means is that when the USDA determines that there is an extraordinary emergency (which, again, it has already done in the context of HPAI) it is vested with broad powers, including the power to kill any animals if it determines that it is necessary to do so to prevent the spread of disease. It is also something that they can check for without a warrant when it comes to:

- Imports of animals into the U.S.;

- Movement of animals between states;

- And transport within a state if there is probable cause to believe that the animal in question is coming from an area that has been quarantined.

If you need another reminder that the focus here is on the human and economic impacts of any given animal disease, check out this page from the USDA, which discusses the emergency management of “foreign animal diseases,” and says, among other things, that ”the strength and success of the U.S. agricultural economy is due in large part to the bonds forged by Government, veterinarians, and producers in preventing, controlling, and eradicating foreign animal diseases (FADs)”. If you want to learn more about the animal health emergency management framework generally in the U.S., you can check out more general guidance here.

Federal Regulations and Administrative Law

As mentioned above in our discussion regarding defining disease, when it comes to implementing statutes, administrative agencies are given both the charge and the discretion to issue their own regulations. These regulations are meant to “fill in the gaps” that Congress left when the statute was issued, from the lens of an agency that has expertise on the matter in question. This is where the Code of Federal Regulations (hereinafter “CFR”) comes in. The CFR is basically the main way that all administrative agencies (like the USDA) issue their guidance. So for example, when it comes to animal diseases, the CFR sets out that USDA vests power in the Veterinary Services branch of APHIS. These powers include but are not limited to the powers to “protect and safeguard the Nation’s livestock and poultry through programs and activities to prevent the introduction and spread of pests and disease of livestock and poultry”.

That’s a big job. APHIS and Veterinary Services take it seriously. They deal with all kinds of diseases in “livestock”, including HPAI, and are responsible for coordination and cooperation with all fifty states when it comes to response measures. If you would like to view the entirety of the USDA’s response plan to HPAI, or its “Red Book” on the subject, you can find that here. Again, this regulatory mechanism has been created because questions around disease in “livestock” and specifically HPAI have raised concerns around two factors that impact human interests: the questions of zoonosisAny disease or illness that can be spread between nonhuman animals and humans. (or possible disease transmission to humans), and the much ensuing and possibly much bigger question for regulating authorities, which is the question of economic impacts of animal diseases on the economy.

On that note, we have to address something here that is potentially upsetting for caregivers or rescuers, but which is yet another question within the purview of USDA powers and discretion and is related to our discussion of animals and economics thus far. This is the question of “compensation” when it comes to birds and eggs that must be destroyed during a disease response. The Animal Health Protection Act authorizes USDA to provide indemnity payments to producers for birds and eggs that must be destroyed when control measures are taken. APHIS also provides compensation for depopulation and disposal activities and virus elimination activities. To learn more about this, please check out this document from the USDA on the HPAI Indemnity and Compensation Process. The relevant CFR provisions can be found here. You might ask why we mention this – after all – as sanctuary caregivers and rescuers, we do not assign a monetary value to the lives of our residents. No amount of “monetary compensation” is worth their lives. We mention it to underscore the general approach of our government to these birds as “commodities,” and also because it will come up again in a discussion below on a sanctuary’s recourse (or lack thereof) in the case of a control measure being exercised that results in depopulation.

On a related note, when it comes to administrative law, there is yet another legal question that we’re going to mention here and consider in greater depth below. There is a concept in law called “the standard of review,” which can get very tricky when it comes to a court assessing the legality of an action taken by an administrative agency. What it means in our context is the level of scrutiny that a court will take in assessing any given action taken by the USDA as regards to HPAI. Stick another pin in this for now, as we will get to it soon. But first, we need to consider how the federal government can coordinate and cooperate with states in emergency disease response situations.

The Question of Federal and State Coordination

It’s important to remember that both federal and state responses to HPAI are very coordinated, although any given state may have its own additional measures and requirements that it can impose on top of what the federal government requires. For example, while low pathogenic avian influenza is not “notifiable” on the federal level, the USDA still coordinates with states when it comes to control measures around it as well as around highly pathogenic strains (and those strains likely to mutate).

If you want to take a close look at the federal level at how this specific example has played out, this guidance document from the USDA may be instructive, as well as this one. While these guidance documents do not hold the “force of law” that either statutes or regulations do, they are very useful when it comes to understanding the general framework that has been used in coordination with states when it comes to HPAI response. It is again important to know that while the USDA is a major player when it comes to control measures around animal diseases, it is not the only one, and there may be instances where state laws impose more stringent responses. However, the interplay that is outlined between the states and the federal government governs a lot of important questions.

So let’s do a quick discussion of questions about the role of state laws, then consider how both can impact the lives of your avian residents:

The Role of State Law in HPAI Control Measures

Here is why it is virtually impossible for us to address any individual question from a sanctuary in terms of what an HPAI detection in their proximity may mean to them, specifically. There are a lot of variations between state laws and policies, even sometimes when it comes to what diseases are “reportable”.

Let’s first consider again what “reportable” even means. We talked about “notifiable diseases” above, in the context of the list that the USDA developed around this question and with regards to the OIE list. So all of those diseases are notifiable – but states can go further than that, and require reporting on even more diseases. Usually what this means is that upon detection of a reportable disease, a treating veterinarian or a facility that keeps farmed animals is obligated to report to their local governing authorities, generally their state department of agriculture. You may be thinking, well, that should be straightforward right? Isn’t there such a thing as a list? How hard can lists be? OIE has a list! The federal government has a list!

There are indeed lists. Many lists! But, state-to-state, disease reporting requirements differ. They differ both in terms of what kinds of diseases are required to be reported, and what timeframe is required in terms of reporting. Since we’re talking about avian influenza, let’s look at the way requirements vary around it so we can explain why this is such a mess in terms of issuing blanket recommendations.

Illinois, for example, requires reporting of all findings of avian influenza, whether they are low pathogenic, or whether they are highly pathogenic, “immediately” (whatever that means since it’s not really defined anywhere). Kentucky does not specifically list avian influenza on its list of reportable diseases in animals, instead deferring to the USDA’s notifiable list and additionally citing the OIE list. New York requires reporting of highly pathogenic strains of avian influenza and certain strains of low pathogenic avian influenza that have a propensity to mutation immediately. Some states get specific about what “immediately” means, some do not, and some use different timeframes.

For anyone trying to navigate this, it gets messy and confusing fast because what Sanctuary A in Alaska might need to consider with regard to reporting requirements is potentially going to be very different potentially from what Sanctuary W in Wyoming is going to need to deal with. For the record, this holds true for all disease reporting, so it’s important for sanctuaries to keep this in mind as a general principle in addition to making themselves familiar with their own local laws!

To make things more complicated, there is a larger question of state enforcement resources. There are some things with little leeway for navigation. For example, in general, the USDA has been involved in virtually every detection and “depopulation” control measure that has taken place in the current HPAI outbreak. What this tends to involve is that when one bird on a site has tested positive for HPAI, all birds on that site are “depopulated,” or bluntly put, killed. We’ll get to this awful subject in a moment. But we do want to point out that there can be grey space depending on your state and its policies and organizational culture when it comes to surveillance-related control measures that are implemented in areas surrounding an HPAI detection.

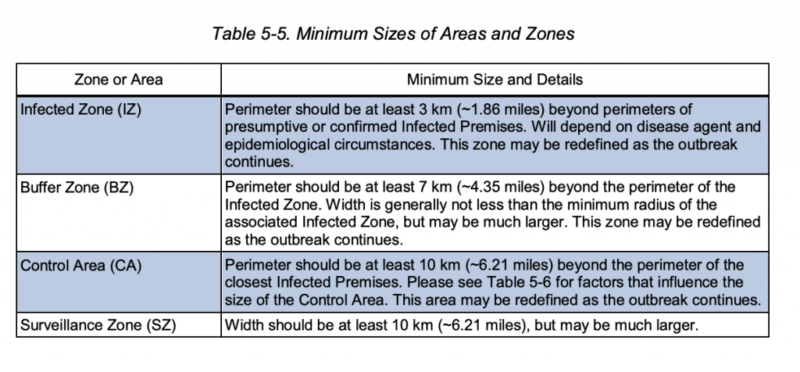

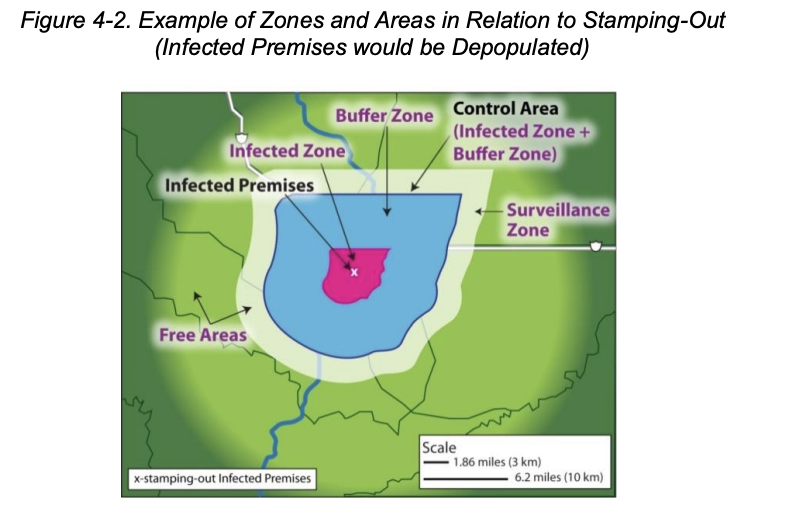

In virtually all cases of an HPAI detection, “buffer,” “control,” and “surveillance” zones (the terms and the radius may differ by state and the specific context of detection and the kinds of control measures used) are instituted around sites with confirmed cases. In such zones, surveillance may be conducted by local and federal authorities to see whether other local flocks exist in the vicinity who potentially may have been exposed. To get a little more specific, the following table from the USDA Red Book illustrates some guidelines around perimeters, but these are not definitive and will be dependent on the state and particular context of a detection.

So let’s think about, for example, caregivers at a sanctuary within a “surveillance zone” who have a written biosecurity plan that was approved by their veterinarian, with written record-keeping that documents (but is not limited to) the following:

- Compliance with that biosecurity plan;

- Careful monitoring of the health of their residents;

- Monitoring of vehicles and people moving on site;

- Closure to, or careful quarantine of intakes as well as traceability of those intakes;

This could potentially make a significant difference in terms of how they may be treated if they are within an area being surveyed.

In contrast, if another caregiver within a surveillance zone has allowed birds to “free-range” (which as a side note, we do not recommend due to predator risks generally) and has taken no biosecurity measures whatsoever – their flock may be scrutinized far more closely, and be significantly more at risk of both having contracted the virus, and the ensuing control measure of depopulation.

What can also make a difference is an organization’s existing relationship (or lack thereof) with local authorities. For example, if a sanctuary has a positive record of communication with their state’s department of agriculture, or agricultural extension services, they may be able to “get ahead of the curve” when it comes to high-risk times and disease. Good communication can help them to institute measures as preferred and advised by their local governments, and thus ensure that they are observing every precaution, even before detections of diseases occur locally, and this may afford them some deference when it comes to control measures.

Again, this may be highly dependent on state laws regarding farmed animalA species or specific breed of animal that is raised by humans for the use of their bodies or what comes from their bodies. diseases as well as the local organizational culture of the state. In states with an economy that is very dependent on animal agriculture, the local laws and organizational cultures may be vastly different from those that are less animal agriculture-dependent.

Fundamentally, while there is no functional way that we can issue universal guidance with respect to the control measures and/or leeway with respect to them that your specific sanctuary may experience with regards to HPAI, you do have control over the measures you take in terms of biosecurity and recordkeeping, and taking such measures can only help to protect your residents.

We can also assist sanctuaries in acquainting themselves with at least some of the state guidance that exists with regard to HPAI and reportable diseases generally. We can provide you with a link, state by state, to their lists of reportable diseases as well as any guidance that they may (or may not have) have issued with respect to HPAI. These lists are included as glossaries at the bottom of this resource.

For further insight, we strongly recommend as always that sanctuaries consult with their veterinarians, local authorities, and local counsel in order to figure out the best parameters possible for a response.

The Really Bad Part: What Does an HPAI Response Look Like?

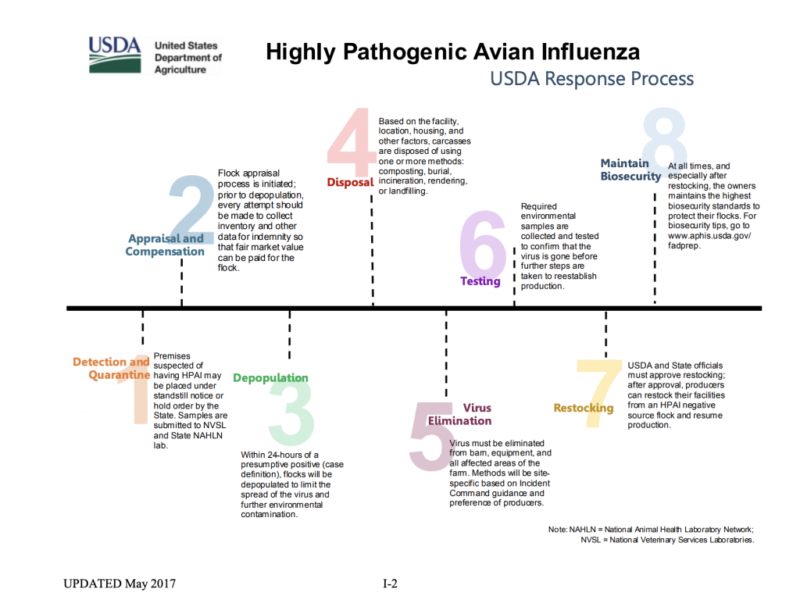

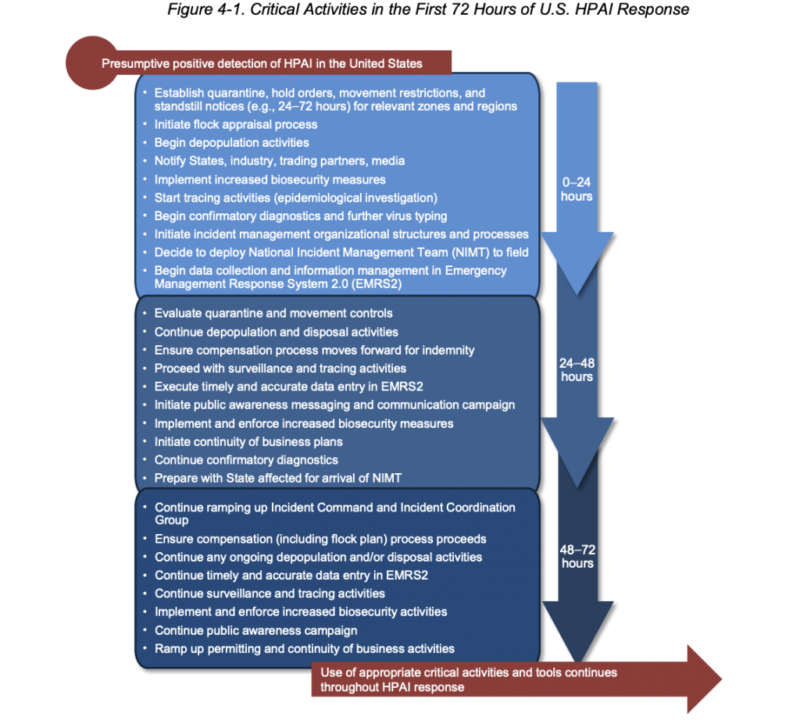

The last major outbreak of HPAI in the U.S. occurred in 2014 and ran through 2015, and there have been minor outbreaks in Indiana in 2016, and in the Southeastern U.S. in 2017 since then. During that time, APHIS developed a lot of plans and guidance. Much of that can be found here. However, as the current outbreak progresses, things may change and this guidance may evolve. Administrative agencies of the federal government in the U.S. tend to have legislative, executive, and judicial powers within their realms, and as mentioned above, these powers can be fairly broad, especially in emergency situations. So again, it’s important to keep track of what the USDA and APHIS are saying with regards to HPAI. It’s also so important for you to keep track of what your state is saying, as again, states have individualized approaches, organizational cultures, and policies derived therefrom which will impact how your sanctuary is dealt with in the case of surveillance in your area. That said, let’s get into the really rough stuff. It’s time to take a stretch, get a cup of tea, and take a deep breath. Let’s start with a graphic from the USDA Red Book outlining the ideal response to the detection of HPAI:

HPAI Detection and Depopulation

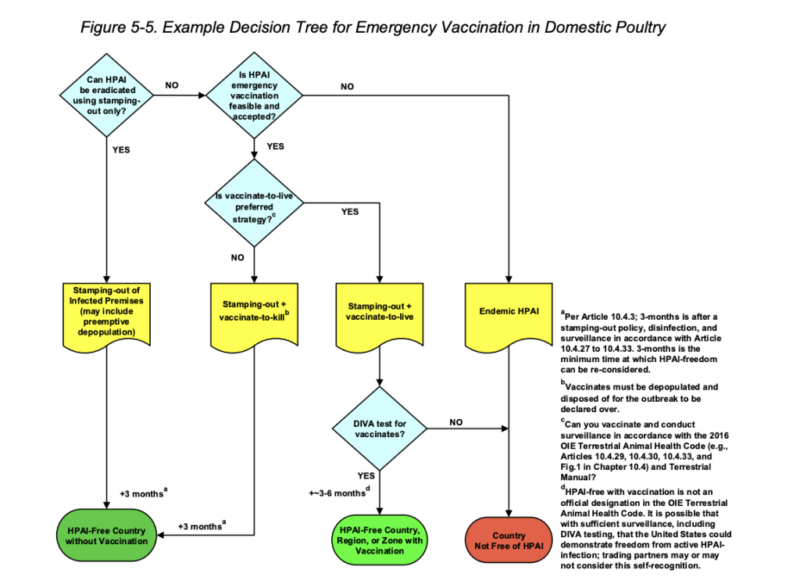

According to the USDA Red Book on HPAI response, “the United States’ primary control and eradication strategy for HPAI in domestic poultry, as defined by international standards and the OIE, is “stamping-out”. “Stamping-out” is defined in the OIE Terrestrial Animal Health Code (2016) as the killing of animals which are affected and those suspected of being affected in the herd and, where appropriate, those in other herds which have been exposed to infection by direct animal to animal contact, or by indirect contact with the casual pathogen; animals should be killed in accordance with OIE Chapter 7.6.”.

It’s important for sanctuary caregivers and rescuers to know what “killed” means in this context, because there is a vast difference in the way that sanctuaries view the question of euthanasia, versus how it is seen in the wider world and specifically, in the context of industrial animal agriculture. While within the sanctuary community, we think about these questions very carefully, and many sanctuaries draft careful and considerate policies around the question of end-of-life care of beloved residents, things are very different in animal agriculture, especially from a government lens when it comes to the killing of animals due to disease risk.

For what it’s worth, APHIS does acknowledge the distinction between mass depopulation and euthanasiaThe act of ending someone’s life to spare them from suffering or a significantly reduced quality of life that cannot be managed., noting that, while “euthanasia involves transitioning an animal to death as painlessly and stress-free as possible. Mass depopulation is a method by which large numbers of animals must be destroyed quickly and efficiently with as much consideration given to the welfare of animals as practicable, given extenuating Specific HPAI Response Critical Activities and Tools…”.

It is further worth noting that the American Veterinary Medical Association (hereinafter “AVMA”) also distinguishes between euthanasia and depopulation. As a matter of fact, the AVMA has developed a totally distinct set of guidelines when it comes to depopulation that is separate and distinct from their euthanasia recommendations and their “humane slaughter” recommendations. The USDA, in fact, also refers to this in the Red Book, with both organizations stating that while as much consideration should be given to the welfare of animals as possible, there are extenuating circumstances that face those who must, by law, conduct depopulation as rapidly as possible, and further that “the emotional and psychological impact on animal owners, caretakers, their families, and other personnel should be considered”. Again, it is unfortunate that consideration of human interests bears a heavier weight than the lives of the animals in question.

With all that said, here’s the worst part: The Red Book provides that “in almost all cases, water-based foam or carbon dioxide are the depopulation methods available to rapidly stamp-out the HPAI virus in poultry. Each premise is evaluated individually, considering epidemiological information, housing and environmental conditions, currently available resources and personnel, and other relevant factors. However, to meet the goal of depopulation within 24 hours and halt virus production, other alternative methods may also be considered by State and APHIS officials”.

There has been some mention by officials who work on the question of HPAI epidemiology and control measures that in certain contexts, the means of killing might be subject to some measure of discretion by the “owner” or caregiver of the birds in question. For example, this question arose in a discussion around HPAI biosecurity and control measures in a webinar held by the Raptor Center, a rehabilitation facility, in conjunction with the University of Minnesota. In this context, the question of the possibility of discretion when it comes to depopulation measures came up, and it was suggested that zoos and rehabilitation facilities might have some leeway, although such organizations are scarcely mentioned in USDA guidance except with regard to “zoological collections” very briefly in the context of potential vaccination, to be discussed below.

It is possible that if such leeway does exist, sanctuaries might also be afforded it, although the general lack of legal recognition of farmed animal sanctuaries makes this less likely. The answer to this question is going to again be “it depends.” This is in part because terms like “zooAn organization where animals, either rescued, bought, borrowed, or bred, are kept, typically for the benefit of human visitor interest.,” “rehabber,” and “sanctuary” also don’t have any kind of overarching legal definitions, let alone even shared philosophical definitions. Again, these kinds of answers are likely highly contingent on the policies and organizational culture of the state in which the detection occurs, as well as the relationship that the sanctuary may or may not have with local officials.

Sadly, we aren’t done with the scary stuff yet. We still need to talk about what can happen in areas that surround the detection of HPAI. As noted above, USDA has statutory authority to conduct surveillance in areas surrounding a detection, and individual states may also have additional laws in place that enable additional control and surveillance measures.

HPAI Investigation Around Infected Premises

Not only is depopulation the fate of all birds on infected premises, but it is also a potential risk for birds in surrounding areas. The Red Book provides that when “criteria for a presumptive positive have been met,” APHIS personnel are authorized in conjunction with State and Tribal officials to initiate depopulation of birds on infected premises. However, they may also be authorized to depopulate “poultry or poultry meeting the suspect case definition, depending on epidemiological information and outbreak characteristics”. This can involve the implementation of a boundary around the infected premises, conducting surveillance therein, and potentially “preemptive depopulation of poultry on other premises in the Infected Zone (typically 3 km around the [infected premises]”.

We know. That’s beyond horrifying information. But what does that look like functionally? The Red Book provides an example of what an “infected,” “buffer,” and “surveillance zone” might look like surrounding infected premises, i.e. those with a known detection.

So what happens in these areas (collectively known as a “control area?”) According to the Red Book, in the initial 72 hours post-HPAI outbreak declaration, “surveillance-related activities” should include potential sampling in all commercial premises and doing outreachAn activity or campaign to share information with the public or a specific group. Typically used in reference to an organization’s efforts to share their mission. to all “backyard premises, with an investigation of those that are deemed to be high risk. The goal is to quickly detect premises with HPAI on site, determining the size and extent of the outbreak, and supplying information on response activities and animal and product movement within the control area.

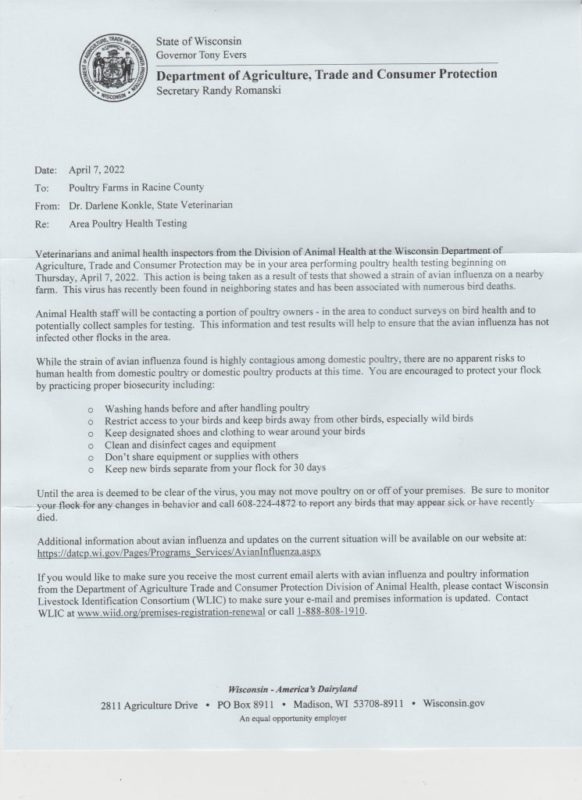

What this looks like, again, will vary state by state. However, to give you an idea, we can share with you an example of a letter received by an avian caregiver from their local authorities, when detection of HPAI was made in their county.

Of course, any caregiver receiving such a letter might feel quite concerned, to say the least. However, here at least we can offer you a glimmer of hope and guidance. As of this writing, it seems that, depending on the state, if a particular site within a “control area” has instituted a robust biosecurity and recordkeeping practice and has no positive test results in residents, that can greatly help guide authorities with regards to their surveillance and decisionmaking – specifically when it comes to depopulation. In such a scenario, it seems the weight of that kind of meticulous biosecurity and recordkeeping combined with no resident positive results would weigh strongly against a decision to depopulate.

All of the prior information is a lot to take in. So to help put it in an easier-to-navigate way, we’ve developed two hypothetical scenarios for you to consider. The first is “the worst-case scenario,” and the second is the “best-case scenario” for sanctuaries finding themselves within control areas:

These Really Are Hypothetical!

All hypothetical scenarios offered in this resource are STRICTLY hypothetical: they are not based on any “real-life situation” but instead are crafted based on our current understanding of the ever-evolving HPAI threat and control measures. They are meant for educational purposes only.

HPAI Surveillance and Control: The Hypothetical Worst Case Scenario

So what’s one hypothetical scenario where we could see how these powers play out from a sanctuary lens? Consider the fictional state of Winnemac, which has had multiple detections of HPAI in both “commercial” and “backyard flocks”. Lucky DuckUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated duck breeds, not wild ducks, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource. Sanctuary is located in the same county as one of the outbreaks. Lucky Duck has twenty domesticated duck residents, and while they are aware of avian influenza, they haven’t taken any measures to address it. Their thinking is that HPAI is not as serious for ducksUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated duck breeds, not wild ducks, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource. as it is for chickens, with many ducks remaining totally asymptomatic, and so they would rather that their residents have full freedom. Their resident ducks still go outside in spite of state-wide warnings to keep birds indoors. They also have a pond on-site, which is shared by wild waterfowl. Lucky Duck is actively posting photos of their residents on social media enjoying the pond alongside some of these wild waterfowl.

There is a very sad and frustrated backyard chickenThe raising of chickens primarily for the consumption of their eggs and/or flesh, typically in a non-agricultural environment. keeper in the same county whose flock was depopulated due to a detection of HPAI. They take note of Lucky Duck’s proximity to their control area, and the social media posts, and start asking questions. “Why is Lucky Duck somehow exempt from the admonitions to keep birds indoors? After all, HPAI does not discriminate right?” Their questions lead to officials paying a visit to Lucky Duck Sanctuary, and inquiring about their biosecurity plans, protocols, and recordkeeping. Lucky Duck Sanctuary can provide none of these. Therefore officials decide to test the residents. When one resident tests positive for HPAI, the matter suddenly is pulled out of Lucky Duck’s hands, and officials make the decision to depopulate the entire resident population.

What can be learned from this hypothetical? We can’t say it enough: Take the threat of the virus seriously. Implement biosecurity measures to protect your residents from contact with wild birds, the droppings of wild birds, or any indirect contact via fomites or contaminated humans, water, vehicles, and so on. Also, consider your social media posts carefully. If Lucky Duck had taken those measures, the outcome here might have been very different. Now let’s look on the brighter side, and consider another way that this could have gone through another hypothetical.

HPAI Surveillance and Control: The Hypothetical Best Case Scenario

We want to make it clear again that this situation with HPAI is not hopelessly and endlessly bleak. There are many things that are within your control, and measures that you can take to protect your avian residents. So let’s envision yet another hypothetical scenario that can help illustrate practices that can help you and your avian residents get through this mess:

We’re revisiting Winnemac. In the county over from Lucky Duck Sanctuary, there is a small bird sanctuary with a variety of species, called Bird World Sanctuary. Bird World has some chickens, some quails, some ducks, and two pigs. When Bird World heard about HPAI in migratory birds in their area, they decided that they were going to do some advance planning. They talked to their local officials about it and got some guidance. They already had their pig residents separated from their bird residents, out of safety concerns around safe cohabitation. Their quail residents already reside indoors. Their duck and chicken residents co-mingled at times, but given the current worries around HPAI, Bird World decides they will make a separate indoor living space for their ducks.

Their separate duck and chicken enclosures are completely covered by tarps in order to prevent the introduction of wild bird feces. They also have fully screened off all these runs using fine mesh window screening, so no birds can enter. They also ensured that the enclosures are fully rodent-proof, to exclude any little creatures who might introduce the virus. They keep their chicken cleaning tools and duck cleaning tools totally separate and disinfect and store all of them indoors after use. They also change clothes entirely and use disposable booties before entering any enclosure. Finally, they called their vet and asked them to come over and assess their biosecurity measures, and sign off on their written plan and checklist. Their vet comes, and further recommends that they make sure that all food and bedding is secured indoors away from any possible contact from wildlife, that they create a checkpoint for delivery vehicles, and that they suspend all visitation to the site pending the end of the HPAI threat. Finally, together they create recordkeeping templates so that Bird World can take daily notes on resident health, cleaning, and biosecurity measure monitoring. Bird World stringently follows all these recommendations and keeps meticulous records.

When HPAI is detected in Bird World’s county, they receive a letter alerting them of surveillance plans at their sanctuary. They meet the responsible officials (some of whom they already knew from past communications) at their checkpoint, greeting them with PPE to put on over their clothes because they don’t know where those officials have been. They have disposable booties for the officials as well which are changed between animal enclosures. They provide officials with all of the records they have kept since the start of the threat. The officials are impressed by these measures, and while they do test some residents, they do not find a positive result for HPAI. Therefore, they urge Bird World to keep up their current measures and hang tight until the HPAI threat has passed. There are no further control, or depopulation measures taken.

So what can we learn from this? Be like Bird World! The careful biosecurity and recordkeeping measures that they took were the very best protection for their avian residents. Not only did these measures protect them from the virus itself, but they were also extremely helpful when it came to responding to surveillance. While there is no guarantee, this work really paid off in this case.

What Else Can We Do? Could We File A Lawsuit?

Understandably, all of this information is depressing and frustrating. Sanctuaries and rescuers may be thinking, what else can we do? Can sanctuaries sue the USDA? Or industrial farmsFor-profit organizations focused on the production and sale of plant and/or animal products.? Or anyone? This is an understandable response. What is happening to birds all across the globe is fundamentally unfair, particularly when it comes to the second prong of HPAI: control measures. Also, because the U.S. does happen to be a remarkably litigious country, it makes sense on some level that our thought processes might jump to this kind of action.

That being said, lawsuits are costly both in terms of monetary resources and emotional energy, and are always associated with significant uncertainty, both when it comes to their ultimate outcomes and possible unintended consequences. It is often questionable whether legal actions actually deliver “justice.” It’s also important to remember that lawsuits have an entirely separate overlay of considerations associated with them due to the distinctions between statutory and common law. Common law, or the law that is defined by having been developed by judges over time, and derived from either likening or distinguishing from previous rulings, is quite distinct from statutory law, or written laws passed by legislatures. Common law is ever-evolving and can differ quite substantially from state to state.

As of this writing, we are unaware of any litigation undertaken to prevent HPAI control measures but will keep our eyes on any developments in this area. The lack of litigation to date likely has to do with both significant logistical and legal barriers, particularly in the context of the current HPAI emergency. It is important to think about these barriers because, in the case of all lawsuits, costs and benefits should be carefully weighed, especially when resources and energy are scarce. Let’s start by considering the logistical barriers:

Logistical Barriers to Lawsuits Over HPAI Control Measures

In the context of a lawsuit to enjoin a depopulation order, there are significant logistical barriers to taking such an action. The first, and probably most critical one, is time. As discussed above, the USDA has developed a comprehensive response to HPAI detections within its Red Book. When it comes to HPAI detection, things start to happen very quickly. The following diagram gives you an idea of what will happen within the 72-hour period that follows a positive HPAI detection in a flock of domesticated birds:

Note that under this plan, depopulation measures begin within 24 hours of a presumptive positive detection. This gives you a really short timeframe to first, get a lawyer, and second, file a lawsuit. Both of these tasks are tricker than they might appear at first glance.

When it comes to getting a lawyer, finding someone in your state who is qualified to file such a lawsuit and having available resources to pay them to do so is a huge challenge in and of itself, especially within the timeframe delineated above! If you can find someone who is qualified and come to an agreement on how they will be paid, then you have another problem: Who are you suing, and are you suing them in state or federal court? Those answers depend on so many factors, and it is very easy to come up with the wrong answer, which can lead to a quick dismissal of any filing made.

If you are able to engage a qualified attorney, come to a mutually satisfactory fee arrangement, file a lawsuit before depopulation measures start taking place, and successfully get a hearing for an emergency injunction issued with regard to control measures, there are still many obstacles to be faced, and these relate to legal questions.

Legal Barriers to Lawsuits Over HPAI Control Measures

Just A Small Sampling Of Challenges

We cannot provide a detailed overview of every potential legal obstacle that might be faced in bringing suit in the face of a depopulation order, or other any other potential litigation a sanctuary could try to bring, because laws can vary by state, and even choice of law provisions can vary by state. Our aim here is only to provide you with some understanding of the legal obstacles any legal actions taken by sanctuaries may encounter.

Understanding Injunctive Relief

Injunctive relief is generally considered to be what is known as “equitable relief,” or the kind of remedy that is only available when there is no adequate remedy at law. It is considered to be a form of extraordinary relief from a court. An injunction directing a party to cease a particular behavior is called a negative injunction, and an injunction directing a party to do a certain action is called an affirmative injunction. Let’s consider these in turn with hypothetical examples of each:

Negative Injunctions

As mentioned above, if you are filing a lawsuit to enjoin control measures, due to time constraints around control measures, you will likely need to seek what is known as an “emergency injunction”. This would be a request for a negative injunction because you are asking for the USDA to refrain from conducting certain activities. If you are successful, you will basically get a temporary order from a court, set for a limited period of time, until the rights of the parties can be fully explored and determined by a court in a more final manner. So how does a court decide on this kind of matter? What kind of standards does it use?

In determining whether to grant injunctive relief, a court has wide discretionary power, and must balance the irreparability of harmThe infliction of mental, emotional, and/or physical pain, suffering, or loss. Harm can occur intentionally or unintentionally and directly or indirectly. Someone can intentionally cause direct harm (e.g., punitively cutting a sheep's skin while shearing them) or unintentionally cause direct harm (e.g., your hand slips while shearing a sheep, causing an accidental wound on their skin). Likewise, someone can intentionally cause indirect harm (e.g., selling socks made from a sanctuary resident's wool and encouraging folks who purchase them to buy more products made from the wool of farmed sheep) or unintentionally cause indirect harm (e.g., selling socks made from a sanctuary resident's wool, which inadvertently perpetuates the idea that it is ok to commodify sheep for their wool). and the inadequacy of damages if an injunction were not granted, against the damages that could result if the injunction were granted. What does this even mean? Let’s first consider a hypothetical example of a suit for a negative injunction:

Let’s revisit Lucky Duck Sanctuary in Winnemac, our hypothetical duck sanctuary described above in the “worst-case scenario.” Let’s imagine that they decided to try to sue to enjoin the depopulation of their avian residents. Let’s assume that they found a lawyer and an appropriate venue for their lawsuit, and were able to file it before depopulation measures commenced. Let’s also assume that their filing convinced a judge to hold a hearing to consider a temporary injunction (Note that there are a lot of big assumptions being made here). The question before the judge at the hearing to determine whether a temporary injunction is appropriate becomes twofold:

First, the judge needs to consider how irreparable the harm to Lucky Duck Sanctuary is with regard to the depopulation. In addressing that question, it is inevitable that the property status of animals will arise. As much as Lucky Duck Sanctuary may value and love their residents, they are still generally considered to be property in the eyes of the law. The other part of this first question has to do with the inadequacy of damages available to Lucky Duck Sanctuary. As mentioned above, USDA has developed a program to compensate “owners” of poultry for the losses sustained as a function of HPAI control measures. It’s extremely likely that given the property status of animals, and the availability of this compensation, a court would consider that the harm of depopulation is not irreparable, and that the existence of a compensation program is sufficient to address Lucky Duck’s damages.

The second question the judge needs to consider is the harm that could occur if they did issue an injunction against the depopulation of Lucky Duck’s residents. As mentioned above at some length, the treatment of farmed animals in this country is largely dominated by an economic lens. Further, the “economic harm” of HPAI has been widely documented by USDA as well as by advocates for industrial animal agriculture. And as mentioned above, there are possible direct risks to humans from the disease, as it is potentially zoonotic. So it seems that in striking this balance, there would be a pretty heavy weight in favor of the court allowing the depopulation, and denying the injunction.

Let’s just pretend for a minute that Lucky Duck’s suit for a temporary injunction succeeded (which is sadly, highly unlikely). At that point, they would be on track to go to trial to secure a permanent injunction. The legal burdens (and the financial burdens) become significantly higher here. The “balancing test” that the court had to engage in to give the emergency injunction morphs into something even more complex and difficult. While again, the tests that a court applies to decide whether a permanent injunction should be granted will vary by state, there is typically a four-part test:

- First, has the plaintiff suffered an irreparable injury?

- Are remedies available at law (including monetary damages) inadequate to compensate for that injury?

- When you weigh the hardships on the plaintiff versus the hardships on the defendant when it comes to the issuance of the injunction, where does that balance lie?

- Will the permanent injunction harm the public interest?

Having gone through the analysis with regards to the question of a temporary injunction for Lucky Duck above, it’s pretty clear that this is a much, much more difficult set of barriers for them to overcome, especially given the fact that both the federal government and the states recognize HPAI to be an emergency, and a risk both to human health and to the U.S. economy as a whole. In particular when it comes to the final question – the question of the public interest – it is really hard to imagine a court that would rule in favor of Lucky Duck Sanctuary and issue a permanent injunction against USDA control measures. Given these legal realities, it seems pretty fair to say that when it comes to protecting their avian residents, Lucky Duck would have been much better served by taking a precautionary approach by implementing careful biosecurity and recordkeeping measures, versus waiting until control measures were being taken in their area and filing a lawsuit after the fact.

Affirmative Injunctions

Let us briefly consider the question of an affirmative injunction in the context of HPAI, as there has been some discussion within the sanctuary and rescue community around actions to compel the USDA to take certain measures. Such ideas include things like filing suit to require the USDA to preemptively exempt sanctuaries from surveillance and control measures, or to require the USDA to allow sanctuaries access to HPAI vaccinations. In the context of HPAI, the question of getting an affirmative injunction is even trickier than that of getting a negative injunction.

To explain why, we’re going to briefly stick our toes back into the Constitution (only briefly!) because some of the legal issues have to do with the question of the “separation of powers”. As we know, there are three branches of government in the United States: an executive branch, a legislative branch, and a judicial branch. (There is a lot of thought and discussion around the administrative state having evolved into a “fourth branch,” but we’ll leave that out of this)! Each distinct branch has unique and exclusive powers. When it comes to the judicial branch, their power is to determine actual controversies between parties, pronounce a judgment with regard to that controversy, and carry the judgment into effect for the persons who brought the controversy before it. They cannot legislate, or make up a law where it doesn’t exist.

As mentioned above, there are no federal legal definitions of the term “sanctuary”, or even of the term “zoo”! The reason why this matters is twofold: First, asking a court for a “blanket exemption for all sanctuaries” would involve requiring the court to craft its own definition of sanctuary, and then to impose that upon the USDA. This would be tantamount to a court legislating, which is a Constitutional no-no! Second, a court is limited to deciding a dispute based on the existence of an actual case or controversy, involving an actually injured plaintiff. The lack of a legal definition of the notion of “sanctuary” means that there really aren’t functional mechanisms within the law for recognizing either the kind of work that sanctuaries do, why it serves a public interest, and why the lives of individual sanctuary residents matter when it comes to that public interest.

This ties into another legal concept, the question of “legal standing”. In essence, the doctrine of standing requires a plaintiff to be able to illustrate an actual “injury in fact”. Let’s talk a bit more about standing to get a better understanding of why it presents a significant obstacle to any sanctuary seeking affirmative injunctive relief:

The Question of Standing

The legal doctrine of standing is often referred to as “that old chestnut,” by animal and environmental lawyers alike. Simply put, legal standing is the question of any given party’s capacity to bring suit in a court. This doctrine has often been used as a barrier to prevent lawsuits when it comes to marginalized humans, questions about the environment, and the protection of nonhuman animals.

Again, legal standing is a major problem in terms of giving legal advice because statutes related to “who is entitled to standing” can vary widely by state and by statute. But we can give you a general overview of some of the considerations here:

- The easiest way to “get standing” is if you have been given it by statute. This happens in some environmental statutes, however there are no federal animal protective statutes that grant it to caregivers, and sparse few states that have statutes that might arguably give sanctuary caregivers standing to sue on behalf of their residents.

- You can also convince a court that you have standing if you are directly subject to an adverse effect by the statute or action in question. However, here there will also be a balancing act engaged in by the court in question that is somewhat akin to the questions that accompany consideration of granting equitable relief, like injunctions, which are discussed above. In this case, the party needs to claim that their standing is based on potential direct harm from the conditions from which they seek relief.

- Finally, you might be able to convince a court that you have standing to bring a lawsuit if you can convince them that even though you are not “directly harmed” by the conditions that you are complaining about, that harm has some reasonable relation to your situation, and that the continued existence of the harm might affect others who may not be able to petition a court for relief.

Those last two sound pretty great, right? Especially that last one. In theory, a sanctuary should be able to squeak into court and say they have standing based on the fact that they have been “harmed” by HPAI and its related control measures, and that those control measures will impact others, right?

The answer is, “maybe”. A sanctuary could potentially argue that, while they have not been subjected to control measures such as depopulation, they have had to take measures to address the two-pronged threat of HPAI: first by taking measures to mitigate the direct health threat from the virus to their residents, costs associated with infrastructure-related biosecurity measures, and second by taking their time, resources and energy to engage in veterinary consultations around HPAI, shutting down tours, doing staff training around biosecurity measures, and so on. A sanctuary could also argue that the fact that their residents will never enter the human “food stream” and that they are valued individuals affords them a different and separate kind of consideration from that given to “commercial poultry.”

All of those arguments may be legitimate to sanctuaries and caregivers. The question is, will a court of law, which is probably unfamiliar with the notion of sanctuary, recognize them in the same way that we, as a community of caregivers, rescuers, and advocates do? That question is very much up in the air. You might get a sympathetic judge. You might not. It all depends. So what does this mean? We’ll look at a possible scenario, once we get through just one more legal concept:

The Standard of Review When it Comes to Agency Action

There’s something known as “the standard of review” in law. We mentioned this above in our discussion of administrative law. It usually comes up when you are talking about an appeal, where a lower court has made a decision, and one party appeals because they are not happy with that decision. The reviewing court will then choose a lens through which to review the lower’s court decision, and that lens is called “the standard of review”. However, it also comes into play when we talk about decisions made by government agencies, like the USDA.

In general, when a court is asked to look at an administrative action, like say, the imposition of HPAI control measures, they will assess whether what they are looking at is a question of fact, a question of law, or a matter of procedure or discretion. A deep discussion of how a court determines this requires legal analysis that is beyond our scope here. To sum it up quickly, probably the best-known articulation of how a court will review an administrative agency’s action was set forth in a case known as Chevron U.S.A. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, which was decided by the United States Supreme Court in 1984. In that case, the Natural Resources Defense Council sued the Environmental Protection Agency (hereinafter “EPA”) to challenge a Clean Air Act regulation.

In that case, in a 6-0 vote, the Supreme Court upheld the EPA’s regulation and established a precedent around the extent to which a federal court, in reviewing a federal agency action, should defer to an agency’s interpretation of a statute. Basically, Chevron established a two-part test. Part one of the Chevron test asks:

- Did Congress express its intent in the statute in question?

- Is the intent ambiguous?

If the intent is clear and unambiguous, then agencies have a clear mandate that they must carry out. If we backtrack to our discussion of the Animal Health Protection Act, we can see from the Congressional findings that underlaid that legislation that Congress clearly found that when it comes to “the prevention, detection, control, and eradication of diseases and pests of animals…regulation by the Secretary [of the USDA] and cooperation by the Secretary with foreign countries, States or other jurisdictions, or persons are necessary” to prevent and effectively regulate interstate and foreign commerce, and to protect the agriculture, environment, and the health and agriculture of people in the U.S.

Just from this, it would seem that the USDA was given a pretty clear mandate by Congress, which means that under the first part of the Chevron test, the inquiry must end, and the court must defer to the will of Congress. But also as noted above, there are some key questions of implementation that Congress left open when it came to the statute. For instance, Congress left the question of defining “animal disease” and an “animal health emergency” almost entirely up to the discretion of the USDA. So, in regards to these questions, a court might consider embarking on the second part of the Chevron test. So in situations like this, where Congress’s intent is unclear, or a statute lacks direct language on a particular point, the reviewing court must decide whether the USDA’s interpretations are based on a reasonable construction of the statute. In determining this, a court will ask the following questions:

- Did Congress intend to leave the ambiguity in the statute?

- If so, then the agency’s regulations are binding UNLESS:

- Regulations are “arbitrary, capricious, or manifestly contrary to the statute.”

- If the statutory ambiguity is not clearly intentional, then a federal court must defer to an agency’s interpretation provided that it is reasonable.

To boil it down succinctly, what the Chevron court established generally with this two-part test is that federal courts reviewing administrative agency regulations and actions will generally offer that agency a wide level of deference, overturning its regulations only when it seems clearly contrary to the stated purpose of a law, or seems totally arbitrary or capricious. That’s a pretty high bar to overcome when it comes to anyone asking a court to second guess an administrative agency. It seems particularly high when it comes to the fairly high level of authority that Congress explicitly delegated to the USDA when it comes to the Animal Health Protection Act. So, unfortunately, again, with regards to a sanctuary seeking equitable relief from control measures, engineering a legal response would be a significant legal obstacle.

Since all this legal talk may have put us to sleep by now, to make this a little bit easier, let’s go back to a hypothetical and give you a concrete story within which you can understand all this tricky rigamarole:

A Hypothetical Lawsuit for Positive Injunctive Relief

Let’s go back to Winnemac. There is yet another farmed bird sanctuary there, known as Birdlandia Sanctuary. They have three turkeysUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated turkey breeds, not wild turkeys, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource., twenty chickens, and seven ducks. After seeing the outcome at Lucky Duck Sanctuary, Birdlandia is on alert. Unlike Bird World Sanctuary (our hypothetical in the “best-case scenario” above), Birdlandia doesn’t have a relationship with their local officials. It just isn’t something they really ever thought about much. But they feel it necessary to speak out and take some action. Even though they haven’t heard anything with regard to possible surveillance in their area, they want preemptive exemption from control measures or access to a vaccine. So they find a willing and able lawyer and come to a fee arrangement with her to file a lawsuit prior to being subjected to any surveillance or control measures.

Birdlandia’s lawyer decides to sue both the state department of agriculture and the USDA in federal court, asking both agencies to declare Birdlandia exempt from any HPAI control measures, particularly from the testing and depopulation of residents. In addition, Birdlandia’s attorney asks for the USDA to release the avian influenza vaccine to Birdlandia, so that they can vaccinate all of their residents and protect them from HPAI. On the surface, this seems like a really good idea, right? The answer is a qualified “maybe”. Because now even though Birdlandia got a lawyer, and put together the resources to pay them, now they have to face the legal hurdles associated with getting an affirmative injunction.

Those hurdles start coming up pretty quickly. Agency attorneys immediately file a motion to dismiss the suit based on lack of standing. Birdlandia goes to court and the first question the judge asks is, “What the heck is a farmed bird sanctuary? Can you point me to anything in state or federal law that is instructive?” Not only is there nothing in federal law, as mentioned above, but Winnemac also doesn’t have any statutes that discuss sanctuary at all. So the judge is confused and unclear on why Birdlandia should be legally seen as distinct or separate from any other “backyard bird flock”.

Furthermore, the judge is also really confused when it comes to why Birdlandia is even bringing suit, given that they have not yet suffered any kind of tangible loss, or had any kind of contact yet with the state department of agriculture, or the USDA with respect to HPAI. So he questions whether there is even a controversy for him to address, and thus whether they have standing to bring the lawsuit in the first place. But out of curiosity, and a desire to make sure he fully hears Birdlandia, he decides to reserve his judgment on the question of standing, and listen to what they have to say. He asks the lawyers to give him briefs on the question of standing. He also asks for a briefing on the question of control measures and the vaccine question.

What he learns from the briefs is that there is existing state and local legislation on the question of “backyard chicken farming”. Winnemac law subjects backyard chicken farming to the same standards as those imposed upon “commercial poultry producers”. In other words, backyard chicken keepers must follow all the same rules, regulations, and guidance that any other “poultry operations” must follow. These include rules with regards to biosecurity in the case of an animal health emergency, as well as compliance with surveillance measures and agency mandates should any disease be found on site.

When the judge turns to the question of USDA’s and Winnemac’s regulations on HPAI surveillance and control, he recognizes from the plain language of the Animal Health Protection Act that Congress explicitly delegated wide authority when it comes to managing animal diseases to the USDA, including the powers to conduct surveillance, and killing diseased animals if necessary, as well as to engage in interstate and interagency cooperation to do so. Therefore, he feels he must, under the Chevron test, defer to the plain language of the statute and the agencies’ decisions with respect to these issues.

The judge also considers Birdlandia’s other request for relief; the request that the USDA be required to issue it avian influenza vaccine sufficient to vaccinate all Birdlandia residents. Here, he becomes more confused and has more questions for the USDA and the Winnemac department of agriculture. He wants to know more about the vaccine so he asks for further information and oral arguments on this question. So, on that note, let’s take a sidebar from “Law and Order: Winnemac Edition,” and make a quick side trip to consider the current legal status of avian influenza vaccines: