We Have A Podcast Episode On This Subject!

Want to learn about this topic in a different format? Check out our episode of The Open Sanctuary Podcast all about the importance of cultivating observation skills as a sanctuary caregiver here!

There is a seemingly never-ending list of skills one must learn in order to provide the high-quality, individualized care one would expect for a sanctuary resident or animal companion. The specific skills you need to learn depend on a variety of factors including the species you care for and each individual’s unique needs, but being observant is a skill that is important regardless of who you care for. Compared to physical skills such as safe restraint, nail/ hoof trimming, or administering medication, observation can be a bit more challenging both to teach and to refine, but being a skilled observer is just as important as proficiency in other caregiving tasks. Thoughtful observation and being able to contextualize and evaluate your observations are important caregiverSomeone who provides daily care, specifically for animal residents at an animal sanctuary, shelter, or rescue. skills that can help you provide the best care possible to your residents.

Through observation, we gather information about what is going on around us, and this can help us learn about or deepen our understanding of a particular species, individual, situation, health condition, etc. We often talk about the importance of responding to an issue- for example, seeking veterinary care if someone is ill or making adjustments to a resident’s living situation if there’s an aspect of it that isn’t working- and this is a very important part of caregiving and providing sanctuary. But in order to respond to an issue, one must first notice the sign(s) that there is an issue and recognize them as such, and this depends on your observation skills and ability to make sense of your observations. Clearly, observation is important, but how can we refine this very important skill?

How Our Brain Processes Information

Before we talk specifically about observation within the context of caregiving, it’s helpful to think about current theories of how our brain processes information.

Please note that some individuals may process information differently than what is described below. Individuals with conditions that affect information processing should consider consulting with or referring to professional guidance regarding how this might impact their observation skills.

Filters, Attention, and Perception

Observation is the process of using our senses to gather information, but our brain can’t possibly process all of the information we gather. This is where filtering comes in.

“Filters help focus our attention on a single task or part of the environment and ignore everything else. What we filter in or filter out depends on where we put our attention. Even though the brain can scan 30 to 40 pieces of information (e.g., sights, sounds, smells) per second, its limited resources mean that most of it is immediately forgotten. This prevents us from becoming overwhelmed.

“Attention is something we have to learn. Through time and practice, we have taught our brain to recognize which signals are important and to prioritize them first so we can quickly redirect our attention to them. And, just as attention is learned, it can also be relearned.”

Improving Observation Skills, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Part of refining your observation skills in the context of caregiving involves teaching our brain what exactly to pay attention to and also how to filter that information, but making sense of what is going on around us requires more than just figuring out what to pay attention to. This is where our perception comes in. According to the same MIT case study, “Perception is taking what we observe and organiz[ing] it to give it meaning.” How we perceive information depends on various factors including our knowledge, values, and past experiences.

Consider this experience that is all too common for folks dedicated to animal care and animal rights

The concept of providing nonhuman animals greater ethical and/or legal consideration to their basic interests, especially the avoidance of suffering and exploitation by humans.: The people in your life who are not as knowledgeable about animal issues might not agree with or even understand your views about animals, but they know you are “an animal person”. As such, with the best of intentions, they send you some animal photo or video that is circulating the internet. While they, and likely the larger population, think the animal featured is “so cute!”, you immediately see all the issues and the ways in which the animal is being exploited (or have serious questions about their well-being). You’re both observing the same animal/ situation, but you have very different perceptions based on your beliefs, values, and knowledge of animals.

The same can occur with observation within the context of caregiving. Two caregivers with different degrees of knowledge and experience may observe the same resident and take in the same information but perceive this information in totally different ways.

Mental Bandwidth

Each of us has limited attentional resource capacity, sometimes referred to as “mental bandwidth”.

“Bandwidth is not some form of “intelligence” (whatever that is), but rather is more like a physiological limit on how much “thinking” we can do in a moment.”

Dr. Tina Bhargava

Because we have a fixed amount of mental bandwidth, how much is available at any given time depends a lot on what we are asking our brains to do. There are two types of information processing, but it is likely that every task requires some mix of the two. Dr. Bhargava describes these processes as:

Automatic processing– This happens fast and fairly effortlessly. Automatic processing is often out of our direct control and happens without us being aware that it is taking place. Automatic processing uses very little mental bandwidth.

Control processing– This process is slow, requires effort, and is regulated. This is the type of processing typically involved when we are processing new information or performing a novel task. Control processing uses most of our mental bandwidth.

We have the capacity to successfully complete multiple automatic processing tasks simultaneously, whereas control processing tasks compete over our limited attentional resources. In terms of how much bandwidth is needed for different tasks,

“Task difficulty and consistency can affect the “cognitive load,” or amount of attentional resources required for a task. Task consistency, in particular, has been shown to be an important factor in whether a task requires control processing or automatic processing. Several studies have demonstrated that the performance of tasks with consistent information-processing demands can be automatized with task practice, thereby freeing attentional resources.”

Dr. Tina Bhargava

While task difficulty, which includes the amount of knowledge needed and the number of problems that must be solved in order to complete the task, can impact which type of processing is necessary, control processing (which, again, requires more mental bandwidth) is typically required to complete novel tasks regardless of their difficulty. It is through the practice of tasks that we shift from using control processing to automatic processing, freeing up more attentional resources. We also develop task strategies that help us to more effectively complete difficult tasks, and as we continue to complete a certain task, we refine these strategies. Through practice, we can automize the consistent components of difficult tasks, again freeing up bandwidth.

So why bring all this up, and what does it have to do with observation? Every caregiving setting is different, but consider all the novel tasks a new caregiver must complete and all the new information they are bombarded with. They are going to be using much more mental bandwidth than a caregiver who has more knowledge (resulting in less new information that must be processed) and who has had time to practice consistent tasks and refine their task strategies (thereby being able to complete tasks, at least in part, through automatic processing). This leaves a new caregiver, or even a caregiver completing a new set of novel tasks, with less available mental bandwidth, and less available bandwidth means less attentional resources to dedicate to “paying attention” to what is going around them outside of the task they are completing.

Observation In The Context Of Caregiving

Now that we’ve looked at how our brain processes all the information around us, let’s look at observation specifically within the context of caregiving.

A Simplified Look At A Complex Process

It’s difficult to distill the complex process of observation into a simple set of steps, but it’s also very challenging to begin incorporating observation into your day without understanding what exactly it entails. Before we attempt to articulate this process, we want to be clear that observation is not a task that you “complete” and then cross off your to-do list. Ultimately, the goal is to train your brain to pay attention to certain information so you can be observant during the course of your caregiving day and not just at designated times.

As you read above, our brain is processing a lot of information at once, and depending on what exactly we are asking it to do, tasks may be competing for limited attentional resources. Unfortunately, it’s not uncommon that a caregiver thinks they are dedicating time to observing residents (after all, the caregiver is in with residents and “looking around”), but because they are multitasking or thinking about what they have to do next, they might not actually be able to process what is going on around them. Therefore, it’s helpful to be intentional about observation time and to ensure you have the attentional resources available to process the information you are taking in. To make SURE you don’t forget to incorporate thoughtful observation into your day, keep this handy mnemonic in mind:

Slow down

Use your senses

Reflect

Evaluate

Keep in mind that these “steps” don’t always happen in a set order, but for folks who are just starting out, following this order can be useful. Let’s look more closely at each “step”:

Slow Down

When you are in with your residents, slow down (or better yet, stop what you are doing entirely) and focus on observation. Remember, our brain can only process so much information at once, so attempting to multitask by observing residents while performing another task runs the risk of observation competing for that limited bandwidth.

Use Your Senses

You can save your sense of taste for your snack break, but pay attention to what you see, hear, smell, and feel (and possibly what you don’t).

Reflect

Consider what you already know that is relevant to the information you are taking in with your senses (for example, if you are observing a group of donkeys, reflect on what you know about donkeys as a species as well as what you know about the specific donkey residents you are observing). Does the information you are taking in make sense based on what you know? Or does something jump out as being out of the ordinary or even outright concerning?

Evaluate

Just because information doesn’t support what you know, that doesn’t necessarily mean something is wrong, but it’s definitely information you want to pay closer attention to. Is this an opportunity to learn something new about your residents? Is something definitely wrong? Or, maybe you still aren’t sure and need to gather more information or consult with a veterinarian or more experienced caregiver.

As mentioned above, observation doesn’t always unfold in this order. Especially as a caregiver becomes more experienced, they may observe something that needs a closer look without first slowing down and being intentional about observation time. Also, in order to fully evaluate a particular piece of information, you may first need to gather additional information by circling through the various “steps” multiple times. Let’s look at a hypothetical example:

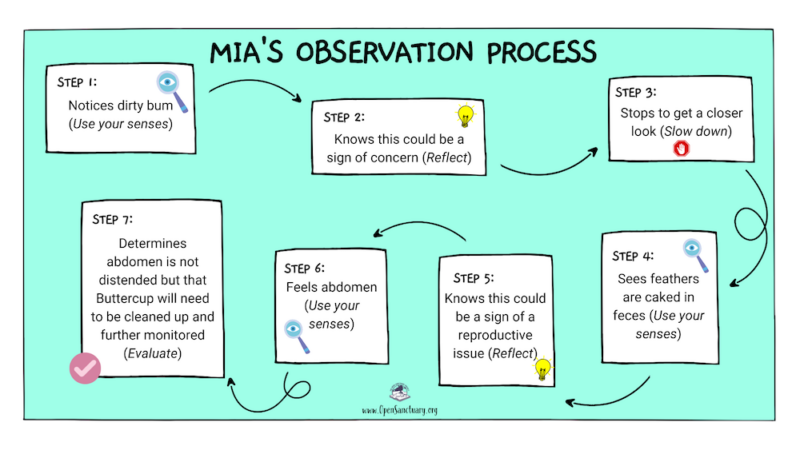

Caregiver Mia is walking past the chicken yard when she happens to notice that Buttercup hen has a seriously dirty bum. From where Mia stands, she can’t tell if it’s poop, mud, or mites, but she knows that whatever it is, it could be a problem that needs to be addressed. Though she was on her way to check on the pig residents, she takes a quick detour to evaluate Buttercup. Before even picking up Buttercup, she sees clearly that her feathers are caked with feces. Recognizing Buttercup’s risk of reproductive issues as a female chicken, and knowing that fecal matting could be a sign of a distended abdomen, Mia decides to investigate further. She picks her up and gently palpates her abdomen to see if she notices anything concerning. Luckily, Buttercup’s abdomen does not feel distended, and Mia does not detect any other issues – Buttercup is bright, alert, has food in her cropA crop is a pouched enlargement of the esophagus of many birds that serves as a receptacle for food and for its preliminary maceration., and looks like her normal self. Mia doesn’t have the supplies with her to clean up Buttercup, so she adds the task to her to-do list and will also make a note of Buttercup’s dirty bum on the healthcare communication whiteboard so everyone knows to pay close attention to if this becomes a consistent issue or if she starts showing other signs of concern.

Let’s look at the process Mia went through while observing Buttercup:

In this example, Mia notices Buttercup’s dirty bum while walking past the chicken area, even though she initially had no intention of going in with the chicken residents. When she notices that Buttercup has a dirty bum, she knows that not only is this not normal, it could be a sign of a potentially serious issue such as a mite infestation or a reproductive issue. Though she doesn’t have the supplies she would need to clean Buttercup up or address a mite issue, she recognizes that it’s important to further investigate what is going on. While it’s still unclear if this was a fluke thing or a sign of something concerning, by cleaning Buttercup’s bum and communicating her findings to the other caregivers, Mia has laid the groundwork for continued observation.

How Our Knowledge Impacts Our Observation Skills

As illustrated in the example above, our knowledge (of the species, breed, individual, situation, health condition, etc.) helps us determine what to focus on and how to make sense of (perceive) the information we take in. To emphasize the role knowledge plays in observation, consider the following information and determine if it is typical (to be expected) or atypical (unusual):

Petunia has a lump with a small amount of discharge on her back, near her tail.

If you made an assumption about who Petunia is, perhaps you made a decision about whether or not this lump is typical or atypical. However, without knowing who Petunia is, particularly what species she is, it’s impossible to evaluate this information. We know Petunia has a lump near her tail, but we don’t know what that means.

Now consider how knowing her species affects the meaning of this information. If Petunia is a turkeyUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated turkey breeds, not wild turkeys, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource. and this lump is her preen glanda large gland that occurs in most birds, opens dorsally at the base of the tail feathers, and usually secretes an oily fluid which the bird uses in preening their feathers (also known as an oil gland or uropygial gland), we’d need a bit more information about her preen gland before we could further evaluate if it is typical or atypical, but the fact that she has this “lump”, which is actually a normal part of her anatomy, is not, in itself, atypical. On the other hand, if Petunia is a pig, the presence of this lump cannot be explained by general pig anatomy.

While this example illustrates the importance of knowing about the species you care for, other areas of knowledge (for example about the breed, individual, situation, health condition, etc.) are similarly important, and different situations will draw on different pockets of knowledge.

Practicing And Refining Observation

So, with all that in mind, where do we start? Because every caregiver and caregiving situation is unique, it’s impossible to offer clear directions for exactly how to start focusing on observation and how to strengthen this skill. With this in mind, let’s consider what observation might look like at different points in a caregiver’s journey, what might be helpful for a caregiver to focus on, and also what might assist in their growth as an observant caregiver.

The Brand-New Caregiver

For the purpose of this section, let’s assume the brand-new caregiver has very limited knowledge of the species they are caring for. Brand-new caregivers are going to be using much more bandwidth than someone with more experience because they are surrounded by new information and are responsible for completing novel tasks. In settings where there are a large number of residents, and caregivers are responsible for completing a long list of novel tasks (say, feeding residents, cleaning habitats, preparing treats, etc.), these tasks will likely be monopolizing a caregiver’s attentional resources. If a brand-new caregiver is part of a team of caregivers, it can be helpful if they can rely on more experienced colleagues to regularly observe residents and watch for signs of potential trouble while they focus on learning how to complete their daily tasks, but we realize this may not be the situation for every brand-new caregiver. Some of the information below is specifically geared towards brand-new caregivers who are part of a caregiving team- check out our textbox below for tips for caregivers who are not part of a larger team.

Potential Focus Areas For Brand-New Caregivers:

- Get the hang of caregiving tasks- Remember, through practicing consistent tasks, you can start relying less on control processing and free up attentional resources, so it makes sense for a brand-new caregiver to focus on the tasks they are responsible for completing and to work on being more comfortable and confident in completing them by following a routine, as much as possible, and working on task strategies.

- Learn (or start learning) the names of residents and how to recognize them– If you don’t already know the residents in your care, make learning their names and how to identify them a priority. Depending on the number of residents, learning everyone’s name might take quite a bit of time, but noticing physical differences and unique characteristics that can help you identify each resident is a great way to start exercising your observational muscles. Also, being able to identify residents will lay the groundwork for learning about each resident as an individual rather than observing residents only as a group.

- Learn more about the species in your care- Identify ways to add to your knowledge of the species in your care. This may take the form of reading informational resources or talking with more experienced caregivers. As you learn something new, try to reinforce that knowledge through observation. For example, say you learn more about what it means that a cowWhile "cow" can be defined to refer exclusively to female cattle, at The Open Sanctuary Project we refer to domesticated cattle of all ages and sexes as "cows." is a ruminant. Next time you are in with your cow residents, pay attention to when they are ruminating and what this actually looks and sounds like.

- Start establishing a baseline– Using the “steps” outlined in the mnemonic above (remember, be SURE to incorporate observation into your daily routine!), start gathering information about the individuals in your care. You may not yet be able to evaluate the information you take in, but even just paying attention to the typical sights, sounds, smells, and sensations you encounter while in with your residents is useful and will help you start recognizing trends and what to expect so you are more likely to notice when something out of the ordinary occurs. For more about observation as a learning tool and examples of the types of things you can learn through observation, check out Observation: An Important Caregiver Tool.

Don’t Discount The Things You Do Notice!

It can be easy for the brand-new caregiver to feel so focused on their daily tasks that they think they aren’t noticing anything. First, take it easy on yourself! And second, don’t discount the importance of the information you are taking in. For example, if one of your tasks is to clean resident living spaces, that probably gives you plenty of opportunities to see resident poop. Perhaps you don’t know the details of how their digestive system works, but you probably have a pretty good idea of what the poop of the different species you care for looks like. That’s important information that can serve you in the future when you come across a strange-looking poop!

Tips For Brand-New Caregivers:

- Be intentional about observation time and make it a habit- Remember, a brand-new caregiver’s brain is being asked to process a lot of information. Don’t skip the “S” in SURE! Definitely slow down or fully stop what you are doing and focus on observation. To help make it a habit, consider incorporating it into your routine so that it occurs in the same sequence daily (perhaps you refill your goat residents’ hay feeders and then take a few minutes to watch them afterward, before moving on to the next task on your list).

- Utilize tools to help you keep track of your observations– Consider carrying a notepad or using your phone to record your observations. Looking back at previous observations can help you establish a baseline and notice trends, and taking notes about an individual’s unique physical characteristics can help you keep track of who’s who.

What About Brand-New Caregivers Who Aren’t Part Of A Larger Team?

Whenever possible, we suggest you learn as much as you can about the species you hope to care for before rescuing or adopting and taking on the responsibility of being someone’s primary caregiver. However, we recognize that things don’t always work out that way, and even if you do spend lots of time learning about a particular species before caring for them, something will eventually come up that you just don’t know how to make sense of. It’s really helpful if you can connect with a network of other caregivers so you have folks to reach out to with questions. Nowadays, there are numerous online communities you can join full of folks dedicated to compassionate care. There are also LOTS of online groups that are not focused on compassionate care- while there may be useful information in these groups, for the brand-new caregiver who isn’t yet ready to be discerning about the information presented, it’s best to stick to groups focused on compassionate care when you can or to at least connect with more experienced compassionate caregivers to get their take on information you glean from non-compassionate sources. And don’t forget about getting veterinary input! If you’re concerned about something, reach out to your vet.

The “Getting The Hang Of It” Caregiver

Let’s assume that the “Getting The Hang Of It” caregiver is able to complete their daily task without having to refer to a list and without a lot of mental effort. This caregiver is able to rely quite a bit on automatic processing to complete tasks and finally feels like they can take in what’s going on around them rather than being hyper-focused on each individual task. The amount of time it takes to move from “brand-new” to “getting the hang of it” will vary. This caregiver might still be very new to caregiving and not have a ton of foundational knowledge, but they have far more attentional resources available than when they were brand-new.

Potential Focus Areas For “Getting The Hang Of It” Caregivers:

- Continue establishing a baseline– Now that you have more bandwidth to process what’s going on around you, really pay attention to what you see, smell, hear, and feel, and notice how your observations change based on other factors such as the time of day or temperature. In addition to paying attention to individual residents, pay attention to how residents interact with each other. Learn more about what they are communicating through their body language and vocalizations. Can you distinguish between playful and confrontationalBehaviors such as chasing, cornering, biting, kicking, problematic mounting, or otherwise engaging in consistent behavior that may cause mental or physical discomfort or injury to another individual, or using these behaviors to block an individual's access to resources such as food, water, shade, shelter, or other residents. behavior? Sleepiness and sickness? Figure out what it means, generally, to be a sheep, goat, chicken, pig, etc. What are their typical physical characteristics and behaviors? What natural processes do they go through, and what does this look, sound, smell, or feel like?

- Report and ask about information that is contrary to your baseline– Remember, not every atypical finding is cause for concern. If you notice something that seems out of the ordinary, be sure to reach out to a more experienced caregiver. If possible, use this as a starting point to learn more. Is what you reported concerning? Is it generally concerning, but not in this particular situation or for this particular individual? It’s also likely that you’ll notice something that is, in fact, totally normal. That’s okay! Instead of getting down on yourself, use this as an opportunity to learn more about your residents!

- Try adding a clear intention– While general observation is useful and important, it’s also helpful to “look” for specific information. Remember, part of refining your observation skills involves teaching your brain what exactly to pay attention to. Start learning more about the most common and obvious signs of concern for the species you care for, and make scanning for that information part of your daily observation. For example, if you care for large breedDomesticated animal breeds that have been selectively bred by humans to grow as large as possible, as quickly as possible, to the detriment of their health. turkeysUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated turkey breeds, not wild turkeys, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource., you might be sure to look closely at how everyone is moving since mobility issues can be quite common.

Tips For “Getting The Hang Of It” Caregivers:

- Try “talking” through what you are observing– It’s really easy to think you are spending time observing residents but for your brain to start wandering. By talking through what you are observing, whether you actually talk out loud or just have an internal dialogue, you can help keep your brain focused.

- Make a cheat sheet– Consider making yourself a list of things to include in your daily observation such as specific signs or behaviors that you want to pay attention to.

The Caregiver With Foundational Knowledge

This caregiver has foundational knowledge of the species in their care and also has become proficient in their daily responsibilities. However, this caregiver may still be working on training their brain to pay attention to certain pieces of information. That is, this caregiver may know that it is not typical for a sheep to drop wads of cudFood matter that returns from the first stomach compartment back to the mouth for further chewing, but they may not yet be to the point where they will notice the signs that a resident has been dropping cud.

Potential Focus Areas For Caregivers With Foundational Knowledge:

- Learn more about your residents as individuals- Now that you have a better understanding of the species in your care, be sure to learn more about each resident as an individual. What makes them unique? Learn more about their personality, preferences, and routines. When observing residents, do so through the lens of who they are as a species or breed and also who they are as an individual. The better you know your residents, the more likely you will be able to notice some of the very subtle signs that something is wrong, which is sometimes simply that someone “isn’t acting like themselves” or isn’t doing what they usually do. For example, if you know that Albert and Cindy geeseUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated goose breeds, not wild geese, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource. are a bonded pair and are always together, then seeing Albert without Cindy would be cause for a closer look.

- Start incorporating observation into other activities- Continue to be intentional about observation, but also start incorporating it into other activities. Now that you can complete most routine tasks without a ton of mental effort, try to pay closer attention to what is going on around you while you are completing tasks. Think back to that example earlier with Mia and Buttercup. Mia didn’t notice Buttercup’s bum during some sort of set observation time. Instead, she had made it a habit to be observant whenever she was in or near residents, and because of this, she was able to notice Buttercup’s bum even though she was simply walking by on her way to the pig barn.

- Start learning how to assess the urgency associated with different concerning observations– Some observations warrant immediate response while others require continued monitoring. Start learning how to determine the urgency of a particular observation so you know how to respond to similar situations in the future.

Tips For Caregivers With Foundational Knowledge:

- Branch out beyond just observing your residents– While observing your residents is essential, in order to ensure their well-being, be sure to observe what is going on around them as well. Observe their living spaces, food sources, etc. for potential issues. This might look like noticing bedding feels wet and then realizing an autowater had been leaking, or noticing information that suggests something might be going on with a resident (such as finding a wad of cud on the ground, as mentioned above).

- Learn more about your residents’ health history– If you don’t already know your residents’ health history, start learning this important information. Knowing someone’s health history can help you determine what specific things to consider during daily observation. For example, if you learn that Diane duckUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated duck breeds, not wild ducks, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource. has had a history of cloacal prolapsethe falling down or slipping of a body part from its usual position or relations, particularly at the start of the laying season, this is something you can be more diligent about checking for.

A Look At Observation As An Experienced Caregiver

As we gain experience, our observation skills become more refined. While there is always more to learn, experienced caregivers have a significant amount of knowledge about their residents and have experience with various situations and health conditions. That’s not to say that experienced caregivers are going to catch every sign of concern or know how to respond to every situation, but observation is now a well-established habit, and they are often able to recognize when something is amiss even when they are in the middle of other tasks.

Let’s revisit the information we learned earlier about attention, as described in the MIT case study: “Attention is something we have to learn. Through time and practice, we have taught our brain to recognize which signals are important and to prioritize them first so we can quickly redirect our attention to them.” Such is the case with the experienced caregiver. They have taught their brain to recognize certain information (such as signs of concern) as important and are able to quickly redirect their attention to that information.

Let’s look at a hypothetical example of what observation might look like for an experienced caregiver:

Caregiver Rae enters the pig barn to hand out morning meds to a few of the older pig residents who have arthritis. It’s early, and the day is cold and dreary, so as they would expect, everyone is still in bed, buried under the straw. As Rae walks through the space trying to figure out which pile of straw Helen pig is sleeping in, they detect a faint sour odor. Usually, the barn smells mostly like hay with a hint of maple syrup- a sour smell is quite unusual. Rae looks around while trying to figure out where the smell is coming from. They notice a small puddle of what appears to be vomit not too far from the autowater unit. Because everyone is still asleep and buried in straw, it’s impossible for Rae to assess everyone so they can try to solve the mystery of who vomited, but given the fact that this could be a sign of a serious issue, they feel it is imperative they get a good look at everyone as soon as possible.

Though it’s not Rae’s responsibility to feed the pigs today, and the pig residents usually don’t eat breakfast for another hour, Rae decides that in order to get a good look at everyone, it makes sense to feed them their breakfast a little early today. Rae connects with the caregiver in charge of feeding so they know Rae will be taking over the pigs’ feeding this morning and then goes ahead and feeds the pigs. Sure enough, as soon as they open the can the pellets are kept in, the pigs are up and running towards their feeding area. Rae looks around making note of who they see and how they look. Everyone is there and eager to eat except Tucker.

Rae feeds the pigs and then goes into the barn to find Tucker, who is still buried in a pile of straw. This in and of itself is concerning, as all of the pigs are always up and ready to go as soon as they hear the food can open. Rae moves the straw off Tucker to get a better look at him and is surprised to notice how warm he feels, especially on a cold day such as today. Rae starts to rub Tucker’s belly, which is usually something that Tucker enjoys, but today, instead of stretching out and exposing his belly, Tucker makes an agitated sound. Each of these findings would be concerning on its own- it’s clear to Rae that something is wrong and they need to consult with their veterinarian. Rae grabs a thermometer from their kit and takes Tucker’s rectal temperature so that they can share this additional piece of information with the veterinarian along with their other observations.

In this example, the first sign that something was wrong was an odd smell, which a less experienced caregiver may not have noticed or may have noticed but not recognized as concerning. Had Rae not noticed this smell, they very well could have missed the puddle of vomit. While the issue with Tucker would have been obvious at breakfast time when he did not come out to eat, it’s possible that the vomit still would have been missed, which would mean one less piece of information for the veterinarian to work with when evaluating him. In this example, Rae’s observation skills lead to the veterinarian being called out earlier than they would have if the issue had not been noticed until breakfast time and also led to the veterinarian having more information than if the vomit had been missed.

It’s important to note that it’s still possible for an experienced caregiver to get distracted, and this can cause them to miss something they otherwise would have noticed. Even though they are able to incorporate observation into many of their daily activities, it’s still a good idea to cut out unnecessary distractions and carve out some time to focus on observing residents.

One Caregiver, Many Journeys

It’s important to note that you can be experienced with one species and somewhere else in your caregiving journey with another species. If an experienced caregiver decides to care for a species they do not have experience with, they’ll need to backtrack a bit and work to gain foundational knowledge of that particular species. They may have certain observational skills down pat, and this will continue to serve them well, but without an understanding of the species they are observing, they won’t know where to put their attention or how to evaluate the information they are taking in through observation.

A Note For Caregiving Supervisors And Trainers

Observation is a skill that should be taught, modeled, and reinforced, so if you are a supervisor or someone who trains new caregivers, be sure to consider how you can help them learn and refine this important skill. In addition to the suggestions below, be sure to give caregivers enough time to incorporate observation into their daily routine!

Suggestions For Supervisors And Trainers Of Brand-New Caregivers:

- Emphasize the importance of observation from the start– When training brand-new caregivers, be sure to introduce the importance of observation during their training and model what goes into the process. If you provide brand-new caregivers with a written checklist of tasks, include observation on the list, but let them know that eventually, the goal will be to incorporate observation into other parts of the day.

- Keep training and shifts as consistent as possible– When designing shifts for brand-new caregivers, remember that consistency and practice are important. If you can, keep shifts as consistent as possible and give brand-new caregivers lots of opportunities to practice and become comfortable with one shift or set of tasks before asking them to work on another.

- Be explicit and have realistic expectations– In team settings, ideally, staff responsibilities should be set up so that residents are seen by more than just a brand-new caregiver. If you expect a brand-new caregiver to observe residents for specific signs, be explicit with them about exactly what to check for (for example, if you expect them to make temperature-related decisions about how to set up a resident living spaceThe indoor or outdoor area where an animal resident lives, eats, and rests., be sure to teach- and ideally show- them signs a resident is too hot or too cold). Simply asking, and expecting, a brand-new caregiver to “make sure everyone is OK” does not give them clear instructions or a realistic goal.

- Make it as easy as possible for them to learn resident names– In order to support brand-new caregivers, be sure to establish ways for them to easily learn who is who. Can you provide photos and descriptions to help caregivers learn everyone’s name? Can you provide more opportunities for brand-new caregivers to spend time with residents while accompanied by a more experienced caregiver who can help them learn who’s who? Can you use non-invasive methods of identification, such as leg bands, to help assist in the process of learning resident names and also to give folks who don’t know someone’s name a way to effectively communicate about them?

Suggestions For Supervisors Or Trainers Of “Getting The Hang Of It” Caregivers:

- Provide more learning opportunities– In settings where caregivers mostly work independently, newer caregivers may not have many opportunities to learn from their colleagues or talk through their general observations. Can you give caregivers the opportunity to shadow a more experienced caregiver every once in a while? Can they assist with health checks, even if they aren’t ready to be trained to perform them? These learning opportunities can go a long way in helping caregivers learn more about the residents they care for and can give them space to ask questions or talk through some of the things they are noticing.

- Model the process that goes into observation– When a situation arises where you are working with newer caregivers, try to model all that goes into observing residents and talk through your thought process. This modeling can help them start a similar internal dialogue and give them an idea of what they are working towards.

- Be patient and encouraging- It’s not uncommon for caregivers who are getting more comfortable with their daily responsibilities to suddenly start noticing more of what is going on around them because they now have more attentional resources available. If they come to you (or someone else on the team) with an observation or concern that is actually information that is not new, but they only just now noticed, make sure the way you (or other members of your team) respond does not make them feel stupid or like they are doing something wrong. Consider this scenario:

Wendell sheep has an enlarged back left leg due to an old injury. A newer caregiver has just noticed this and shares their observation with a more experienced caregiver: Newer Caregiver- Hey, I just wanted to let you know that Wendell’s leg looks weird, like maybe it’s swollen or broken or something? It’s way bigger than the other one. More Experienced Caregiver- Yeah, I know. It’s from an injury that happened a long time ago. The newer caregiver might feel stupid or like they’re “bad” at caregiving for not noticing this sooner. They may even be reluctant to share future observations which could result in signs of concern not being shared in a timely fashion. Instead, strive for a response that is something like this: More Experienced Caregiver- Good observation! In anyone else, this would definitely be cause for concern, so thank you for letting me know. In Wendell’s case, his leg is bigger due to an old injury and this is his new normal. If you ever notice it looking bigger than this, or if you ever notice him limping, definitely let someone know. In the above response, the “getting the hang of it” caregiver is able to learn something new about Wendell without being made to feel like their observation was stupid or wrong. They now have a baseline for him and clear things to look for going forward. We all have bad days and supervisors and trainers likely have a lot on their plate, but strive to create an environment where everyone feels comfortable sharing their observations and asking questions!

Suggestions For Supervisors Of Caregivers With Foundational Knowledge:

- Continue to offer learning opportunities, especially around determining the urgency of a particular finding– As caregivers bring up their observations or as you navigate a particular situation with them, be explicit about the appropriate response and urgency of the situation so they can start learning more about how to evaluate their observations. If it is reasonable to take the extra time to do so, as they learn more, consider asking them what they think their observations mean and what should be done next. This will give you both a chance to understand where the caregiver is at and will allow you to provide feedback.

- Make it easy for caregivers to learn residents’ health histories– Find a way to make resident health histories and records accessible to caregivers and give them time to look at these documents. You might also use health checks or other caregiving activities as opportunities to do some storytelling and history sharing about residents.

We’ve covered a lot of information, so let’s do a quick recap: Observation is the process of using our senses to gather information, but because we can only process so much information at once, we have to learn what to pay attention to and how to filter that information. We also have to make sense of this information. Our ability to do this is dependent on our knowledge, so as we learn more about the individuals we care for, we can develop and further refine our observation skills (what our brain pays attention to and how we perceive that information). This is a continuous process- learning more, refining our observation skills, learning more, etc. Remember, observation is not a task you complete and cross of your to-do list, but is instead something that should permeate into most of what you do as a caregiver. Similarly, becoming an observant, experienced caregiver is not a destination, it’s a journey.

SOURCES: