Veterinary Review Initiative

This resource has been reviewed for accuracy and clarity by a qualified Doctor of Veterinary Medicine with farmed animal sanctuaryAn animal sanctuary that primarily cares for rescued animals that were farmed by humans. experience as of May 2023.

Check out more information on our Veterinary Review Initiative here!

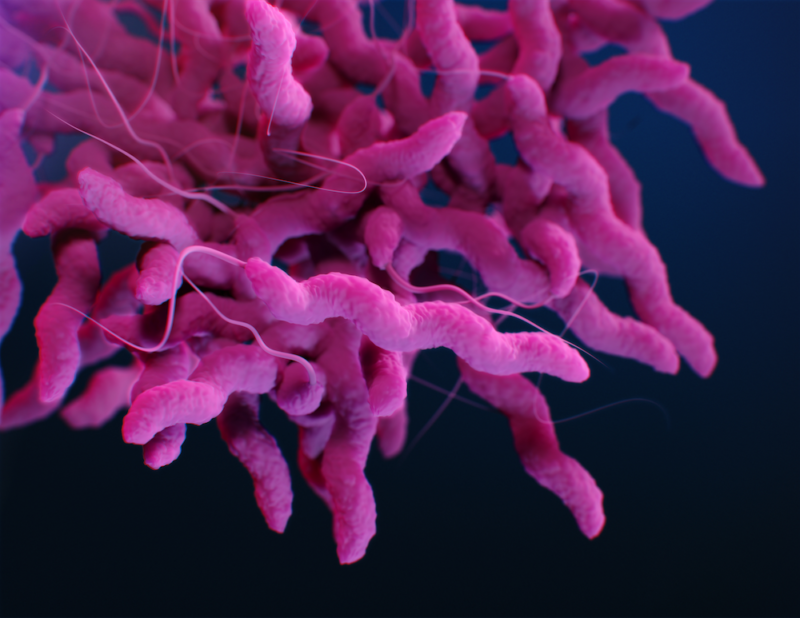

Infectious diseases are caused by organisms (often microorganisms) such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, helminths (parasitic worms), or protozoa. While there are a staggering number of these organisms, only a fraction of them are harmful – those that have the potential to cause disease are referred to as pathogens or as being pathogenic (or, more simply, as infectious agents). Examples of infectious diseases that affect farmed animalA species or specific breed of animal that is raised by humans for the use of their bodies or what comes from their bodies. species include mycoplasmosis, pox, ringworm, pinkeye, coccidiosis, and influenza, just to name a few.

How Do Infectious Diseases Spread?

It’s important to recognize that infectious diseases do not occur at random. Instead, disease is the result of complex interactions between the organism, host, and environment. This is referred to as the epidemiological triad. Let’s take a quick look at each of these categories of determinants:

Organism (often referred to as the agent) – These determinants include:

- Type – bacteria, virus, fungus, helminth, protozoa, etc.

- Pathogenicity – this refers to whether or not the organism has the potential to cause disease

- Virulence – this refers to the degree at which the organism causes disease (how transmissible, severity of disease, ability to evade vaccines, etc.)

- Host Range – this refers to the species that can be infected (some organisms can only cause disease in one species while others can affect multiple species – diseases that can be transmitted between humans and non-human animals are called zoonotic diseases and are discussed more below)

- Route(s) Of Transmission – this refers to how the pathogen is spread (more on this below)

- Life Cycle And Replication Rate – this refers to development of the organism and how quickly it replicates/reproduces

- Environmental Persistence – this refers to the organism’s ability to survive in the environment, which may require very specific conditions (temperature, humidity, etc.)

Host – These determinants include:

- Age – very young individuals, as well as elderly individuals tend to be most vulnerable

- Breed – within a species, some breeds may be more or less resistant to infection than others

- Immunity – in some cases, individuals who have been vaccinated or have already been exposed to the organism may be less likely to develop disease than an unvaccinated individual or someone who has not previously been exposed

- Overall Health And Well-Being – individuals with pre-existing conditions or who develop co-infections could be more likely to develop more serious disease than someone who is otherwise healthy. Additionally, individuals who are stressed and/or malnourished are often more vulnerable to disease.

Environment – These determinants include:

- Geographical Location – some pathogens are more prevalent in certain regions, and factors such as the presence of wetlands, proximity to natural spaces teeming with wildlife, or proximity to farmsFor-profit organizations focused on the production and sale of plant and/or animal products. could also increase the likelihood of certain pathogens being present in the environment.

- Climate/Season – depending on the conditions necessary for the organisms to survive and replicate, some diseases are most likely to occur in certain climates or during certain seasons. Climate and season can also have an impact on whether or not certain vectors (discussed more below) or intermediate hosts are prevalent.

- Housing – certain housing elements can affect the likelihood of an individual being exposed to a particular pathogen, and other housing elements can affect an individual’s overall health (and, therefore, their ability to fight infection)

- Care Practices – certain care practices can increase (or decrease) the likelihood of an individual being exposed to a certain pathogen in the first place or the likelihood of being exposed to the pathogen in high enough numbers to actually cause disease (the minimum number of organisms required in order to cause an infection in a susceptible host is called the infective dose). Care practices include things like how individuals are housed, cleaning practices, feeding practices, how resident supplies are stored, etc.

Different diseases require different interactions between the above determinants. However, a common thread is that in order for infection to occur, a susceptible host must be exposed to the pathogen and the pathogen must be able to enter the body. Depending on the organism, there may be a variety of ways the disease can be transmitted, or there may only be one specific way the disease can be transmitted. We’ll take a look at some of the more common routes below.

One concern that comes up when thinking about infectious disease is the risk of an infected individual spreading the disease to others. Infectious diseases that can be spread from one individual to another are considered communicable (or contagious). While all communicable diseases are caused by pathogens and are, therefore, infectious, not all infectious diseases are communicable. Examples of non-communicable infectious diseases that can affect farmed animal species include aspergillosis and tetanus. These diseases cannot be transmitted from one individual to another. However, if one individual in a group develops disease, others in the group may also be at risk if the infected individual came into contact with the infectious agent in their shared living spaceThe indoor or outdoor area where an animal resident lives, eats, and rests..

Exposure

There are a number of ways individuals may be exposed to infectious diseases. Depending on the way(s) in which a particular pathogen spreads, there may be multiple ways in which an individual can be exposed or there may be one specific route. We’ll take a closer look at the main routes of infectious disease exposure below, but keep in mind that when considering how a specific pathogen spreads, not all of the below routes will apply.

The main routes of disease exposure are as follows:

Direct Contact – This type of exposure occurs when an individual comes into direct physical contact with an infected individual, their tissues, or their bodily excretions, secretions, or fluids. Examples of direct contact include individuals in a shared space rubbing up against each other or individuals in separate but neighboring areas making nose-to-nose contact through a fence. Some diseases can be transmitted from mother to baby in utero. This is considered a subset of direct contact and is often referred to as vertical transmission.

Aerosol – This type of exposure occurs when pathogens become suspended in the air, which may occur when an infected individual breathes, coughs, or sneezes. Pathogens can also become airborne if contaminated soil or dust gets stirred up, which may occur when living spaces are being cleaned or simply when individuals are moving around a contaminated space.

Oral – This type of exposure occurs when an individual ingests pathogens (which may occur if their food or water becomes contaminated) or when an individual comes into contact with pathogens when chewing, licking, or suckling on someone or something. The fecal-oral route is a very common transmission route. This entails a susceptible host ingesting feces from an infected individual and goes far beyond blatant coprophagy. Fecal-oral transmission may occur in various situations, such as if food or water becomes contaminated with infective feces or if an individual ingests infective feces while grooming or nursing.

Fomite – This type of exposure occurs when an individual comes into contact with a pathogen via a contaminated inanimate object (called a fomite). Things like cleaning tools, feeding supplies, brushes, coats, bedding, and equipment can be fomitesObjects or materials that may become contaminated with an infectious agent and contribute to disease spread. Though far from the only fomite of concern, used needles can transmit diseases, so the practice of using one needle on more than one individual (such as while vaccinating an entire group) should absolutely be avoided. Vehicles can also act as fomites, carrying pathogens onto sanctuary grounds on their wheels or undercarriage. When humans introduce pathogens carried on their shoes or clothes to an individual, this is also considered fomite exposure.

Vector-borne – Whereas fomite exposure occurs when a pathogen is introduced via an inanimate object, vector-borne exposure occurs when the pathogen is introduced by a living organism. There are two types of vector-borne transmission: biological and mechanical. Biological transmission occurs when a vector, such as a blood-sucking insect, uptakes a pathogen that then replicates and/or develops inside the vector. The biological vector can then transmit the pathogen to a susceptible individual. Common biological vectors include ticks, lice, and mosquitos. Unlike biological transmission, in which the pathogen replicates and/or develops inside the vector, during mechanical transmission, the vector simply carries the pathogen on their body. Flies, gnats, and rodents can act as mechanical vectors of certain diseases. Humans can act as both biological and mechanical vectors of various diseases.

Looking For More Information?

The Center For Food Security and Public Health (CFSPH) offers lists of disease exposure routes (including whether or not they are zoonotic) for cowsWhile "cows" can be defined to refer exclusively to female cattle, at The Open Sanctuary Project we refer to domesticated cattle of all ages and sexes as "cows.", equines, small ruminants, pigs, and farmed bird species. While much of their information is intended for commercial animal agricultural operations, folks looking for more information about infectious disease transmission may find these lists useful. To access them, follow this link and choose “Specific Diseases By Exposure Route” in the column on the left.

Entry Into The Body

Exposure is just the first step. In order to cause infection, the pathogen must enter the body of a susceptible host and access the area(s) where it can replicate or where a toxin it produces can act. The main routes of entry are via broken skin, mucous membranes, and the gastrointestinal tract. From there, disease may or may not develop based on the determinants described above.

Post-Exposure Outcomes

Just as not every individual who is exposed to a pathogen will become infected, not every individual who becomes infected will develop obvious signs of illness (clinical disease). Infectious diseases often have a range of potential clinical outcomes referred to as the spectrum of disease. This spectrum may range from subclinical infection (in which the host shows no obvious signs of disease) to mild, moderate, or severe disease, with the determinants described above influencing the development and the severity of disease. CFSPH offers the following examples to illustrate how the interplay between the determinants described above can affect the clinical outcome:

- A highly virulent pathogen may cause severe disease in all hosts, regardless of their health status

- An immunocompromised host may develop clinical disease, even when an infection is asymptomatic [subclinical] in other animals

- A crowded, dirty environment can harbor a high pathogen load (large numbers of pathogens), resulting in increased exposure and possibly increased disease severity

Subclinical Infection

Infection without outward signs of disease is referred to as subclinical infection. Because there are no obvious signs of illness, subclinical infections often go undetected. Individuals with subclinical communicable infections can be a source of disease spread to others, though the period during which they are infectious (able to spread the infection) varies depending on the pathogen. These individuals are often referred to as ‘carriers’ or ‘silent shedders.’ In some cases, diagnostic testing can identify individuals with subclinical infections, but the accuracy and reliability of testing varies depending on the pathogen of concern and the specific test that is used.

Clinical Disease

In cases where infection does ultimately result in clinical disease (observable signs of illness), the specific clinical signs the individual develops will depend on the disease (for example, a respiratory disease may result in coughing and labored breathing, while a gastrointestinal disease may result in diarrhea). The interplay between the determinants described above affects not just whether or not the individual develops clinical disease, but also how severely they are affected. The duration of clinical disease may be brief or prolonged, with some infectious diseases resulting in chronic, lifelong disease.

The period between exposure and the onset of clinical signs is referred to as the incubation period. Different pathogens have different incubation periods, with some having very short incubation periods (hours to days) and others having long incubation periods (years). Some diseases have very consistent incubation periods, while for others it can be quite variable. As with subclinical infections, the period during which the individual is able to spread a communicable disease depends on the infection. Some infections result in an individual becoming infectious before they are showing clinical signs of illness, and some infections result in the individual remaining infectious even after signs of illness resolve. Depending on the disease, the individual may remain infectious for a limited period of time or for the duration of their life. Individuals who are infectious for life are often called ‘lifelong carriers.’

What Are The Consequences Of Infectious Diseases?

Infectious diseases that can affect farmed animal species range from those that typically cause very minor illness to those that are almost always fatal. Some infectious diseases can be treated with appropriate medications that kill or slow the growth of the causative agent, while others have no direct treatment. Some infectious diseases can be prevented or minimized through the use of appropriate vaccines (as recommended by your veterinarian), while other infectious diseases have no approved vaccines available. As a result, some infectious diseases carry more serious consequences for infected individuals (and those around them) than others. There’s a big difference between a brief, mild illness and one that will cause lifelong disease, and there’s also a big difference between a potentially fatal disease that has an effective vaccine and/or treatment available and one that has neither of those things.

In addition to the impact the disease itself has on an infected individual, it’s also important to understand other consequences that can come with certain infectious diseases. The first topic to consider in terms of potential consequences is that of zoonotic diseaseAny disease or illness that can be spread between nonhuman animals and humans.. You can read more about zoonotic disease here, but we do want to stress that the spread of a zoonotic disease from a sanctuary resident to a human volunteer, guest, or staff person could have major implications for sanctuary residents and your organization as a whole, particularly if a human becomes seriously ill.

The other topic to consider in terms of consequences is that of reportable diseases. These are diseases that, when suspected or confirmed by a veterinarian, diagnostic lab, or other animal health professional, must be reported to the appropriate governmental agency. Within this broader group of diseases are those that are considered emergencies and legally require near-immediate notification to designated officials or agencies. Setting aside the impacts of the disease itself on residents, these reportable diseases are typically the ones that trigger a swift response from governmental agencies and that may put residents at risk of government-mandated killing as part of containment and eradication efforts. Therefore, in addition to prioritizing the prevention of dangerous infectious diseases, more generally, sanctuaries should also prioritize preventing exposure to pathogens that put residents at risk of their government’s eradication measures.

Folks in the US can find a list of nationally notifiable diseases and conditions here, but you’ll also want to familiarize yourself with reportable diseases in your state. Not all disease reporting ends with government-mandated killing – in many cases, reporting is used to monitor endemic diseases, and this reporting may have no meaningful impact on your organization or residents at all. For more information on this subject and the reportable diseases that are most concerning in your area, we recommend reaching out to your veterinarian or local department of agriculture.

Preventing Infectious Diseases

After all this information about infectious diseases and the potential consequences they can carry, you’re likely wondering how you can protect your residents. If you are dealing with a specific infectious disease, be sure to work closely with your veterinarian to determine the most appropriate steps both for the affected individual, as well as the rest of your residents (if you happen to be wondering how to protect your residents during the ongoing outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza, HPAI, you can check out our resources here). When thinking about infectious disease prevention more generally, in addition to promoting resident health through good care practices, you should also adhere to biosecurityMerck Veterinary Manual defines biosecurity as ”the implementation of measures that reduce the risk of the introduction and spread of disease agents [pathogens].” measures that reduce the risk of infectious agents being introduced to or spread around your sanctuary. You can find our resource on biosecurity here!

SOURCES:

Germs: Understand And Protect Against Bacteria, Viruses And Infections | Mayo Clinic

Disease Exposure Routes | The Center For Food Security And Public Health (Non-Compassionate Source)

Biosecurity: Routes Of Disease Transmission | The Center for Food Security And Public Health (Non-Compassionate Source)

Introduction to Veterinary Epidemiology | Dirk Udo Pfeiffer (Non-Compassionate Source)

Biosecurity in Livestock and Poultry Production: Basic Course | The Center For Food Security And Public Health (Non-Compassionate Source)

Non-Compassionate Source?

If a source includes the (Non-Compassionate Source) tag, it means that we do not endorse that particular source’s views about animals, even if some of their insights are valuable from a care perspective. See a more detailed explanation here.