Veterinary Review Initiative

This resource has been reviewed for accuracy and clarity by a qualified Doctor of Veterinary Medicine with farmed animal sanctuaryAn animal sanctuary that primarily cares for rescued animals that were farmed by humans. experience as of February 2024.

Check out more information on our Veterinary Review Initiative here!

Veterinarians can use various diagnostics tools to help paint a picture of what is going on inside a patient’s body, but sometimes they actually need to “see” for themselves. This is where diagnostic imaging comes in! Imaging allows veterinarians to look inside a patient’s body in a non-invasive way so they can gather additional information to aid in making a diagnosis (or to monitor an ongoing condition) and provide a prognosis. In this resource, we’ll provide a brief overview of the types of imaging technology most commonly used in veterinary medicine. However, please remember that your veterinarian is the person best equipped to determine if and when diagnostic imaging is warranted and which type(s) of imaging will be most appropriate.

A Focus On Farmed AnimalA species or specific breed of animal that is raised by humans for the use of their bodies or what comes from their bodies. Species

If you’re not familiar with our work, we should point out that while many of our resources can be applied to a wide range of animal species, our primary focus is on species that are traditionally farmed. This includes avian species, such as chickens and ducksUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated duck breeds, not wild ducks, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource., and mammalian species, such as pigs and goats. If you are looking for information about diagnostic imaging for dogs or cats, please be aware that these species are not our focus here, and some of the information described below may not apply to them. In addition to consulting with your veterinarian for more information, you can find numerous online resources discussing diagnostic imaging for cats and dogs.

Radiography (X-Ray Imaging)

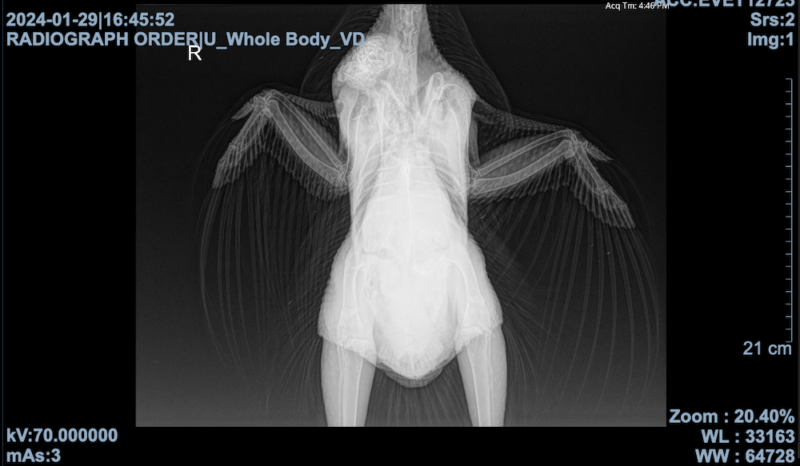

This is the most commonly used imaging procedure in veterinary medicine and likely one most folks are familiar with in human medicine. During this procedure, an X-ray beam is passed through a specific part of the body and onto specially treated plates or digital media to create a two-dimensional image called a radiograph (or X-ray). Radiographs were once solely captured on film, but nowadays, digital radiographs are common. Different structures in the body allow different amounts of X-rays to pass through them, creating an image of black, white, and shades of gray. Soft tissues allow most of the X-rays to pass through and will appear dark gray on the image. More dense structures allow few X-rays to pass through, with the most solid structures appearing white in the image. In some cases, a contrast agent is used to better visualize certain structures in radiographs.

Your veterinarian may recommend X-ray imaging to help diagnose diseases of the chest, abdomen, or musculoskeletal system. Depending on the concern, your veterinarian may recommend performing radiographs and an ultrasound to gather more information (the two imaging techniques are often considered complementary tools, with radiography better at evaluating skeletal structures and ultrasonography better at evaluating soft tissue structures).

Examples of situations where your veterinarian may recommend radiographs be taken include, but are not limited to, the following:

- To check for or locate a foreign body in the digestive tract after confirmed or suspected ingestion

- To check for bone fracture in an acutely lame patient

- To assess bone involvement in a patient with a foot infection

- To check for signs of joint disease and to monitor its progression

- To evaluate lungs for signs of pneumonia

- To check for masses in certain parts of the body

- To further evaluate the teeth after finding an abnormality during a dental exam

Performing X-Rays On Site

Some mobile veterinary practices may have a portable X-ray machine they can use to perform X-ray imaging at your sanctuary. If needed, these images can be sent to a specialist for interpretation. However, depending on the situation, your veterinarian may recommend the individual have radiographs taken at a veterinary hospital instead. When taking X-rays on site, sanctuary personnel may be enlisted to assist in the process, perhaps by restraining the resident or holding the digital media in place. If sanctuary personnel must assist in the process and remain in the space with the individual while the radiographs are taken, your veterinarian should provide them with appropriate protective gear, including a lead apron (or equivalent), thyroid collar, and gloves in order to reduce radiation exposure. Pregnant people should not be tasked with assisting with radiographs due to the risks associated with radiation exposure.

Whether radiographs are taken in a hospital setting or on site using a portable X-ray machine, the process itself is painless, non-invasive, and relatively quick. Capturing the image takes a fraction of a second, but time is needed to properly position the individual and the machine in order to capture the most useful image. In some cases, multiple images may be necessary to see different parts of the body and/or certain structures from different angles. The individual must remain still to get the clearest image possible. In some cases, patients can be radiographed while physically restrained and fully awake. However, some situations may require the use of sedation to help keep the patient still (and to reduce the need for physical restraint, which will expose personnel to radiation). Your veterinarian may recommend that small animal species, such as chickens, be anesthetized for radiographs depending on the part of the body being imaged.

Ultrasonography (US)

This is another commonly used imaging technique in veterinary medicine. During the procedure, your veterinarian or a trained ultrasonographer uses a hand-held device (called a transducer) to expose parts of the body to high-frequency sound waves (ultrasound). During an external ultrasound scan, the transducer is held against the body and moved over the skin. A liberal amount of gel is used to facilitate easy movement of the transducer over the skin. During an internal ultrasound scan, the transducer is inserted into the body (often rectally and usually only in large animals such as cowsWhile "cows" can be defined to refer exclusively to female cattle, at The Open Sanctuary Project we refer to domesticated cattle of all ages and sexes as "cows."). The sound waves travel through organs and tissues and are either reflected or absorbed, producing an echo. A receiver in the transducer records these echoes, which are then sent to a computer that produces real-time images on a monitor. Whereas a radiograph is a static image, like a photo, an ultrasound is more like a movie (though the person performing the ultrasound may also capture still images during the procedure).

Your veterinarian may recommend ultrasonography if they need to visualize soft tissues or organs in real-time, and, as mentioned above, ultrasonography is sometimes used in conjunction with radiography. Your veterinarian may also recommend the use of ultrasonography to guide needle placement for biopsies or fluid sample collection. However, ultrasound waves cannot penetrate bone and are disrupted by air/gas, so your veterinarian will consider this when determining if an ultrasound is worth pursuing.

Examples of situations where your veterinarian may recommend performing an ultrasound include, but are not limited to, the following:

- To evaluate the reproductive tract (including checking for pregnancy in mammals)

- To evaluate tendons, ligaments, and joints in a patient who is lame

- To help determine if a mass can be safely removed

- To evaluate the gastrointestinal tract in a colicking patient

- To check for urinary calculi in the bladder

- To evaluate specific organs, including the heart (echocardiography), lungs, liver, etc.

Ultrasounds are painless and can be done relatively quickly. They are often done while the patient is awake, though there may be times when your veterinarian recommends the patient be sedated. During an external ultrasound scan, your veterinarian will need to take steps to ensure the transducer makes continuous, complete contact with the skin. In some cases, they will be able to part the individual’s feathers or hair using rubbing alcohol, but other times, feathers may need to be removed, or hair may need to be shaved in order for the transducer to make direct contact with the skin.

As with X-ray machines, ambulatory practices may have a portable ultrasound machine they can use to perform the procedure at your sanctuary. However, the quality/diagnostic value of the images produced will depend on the skill of the person performing the procedure. Therefore, while your veterinarian may choose to perform an ultrasound in certain situations (for example, to check for pregnancy in a new arrival), there may also be times when they recommend having the procedure performed by an experienced ultrasonographer.

Advanced Imaging

Though not as commonly used as radiography or ultrasonography, there may be times when your veterinarian recommends advanced imaging such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). We’ll briefly discuss each of these below, but we want to point out that accessibility to these diagnostics will depend on various factors. Advanced imaging may not be an option depending on the species in question and the part of the body that needs to be evaluated. This is particularly true with large animal species who may not be able to be accommodated by most facilities’ equipment. While there are CT and MRI machines designed specifically for horses, there still may be limitations in terms of which parts of the body can be scanned.

Another factor that may make access to advanced imaging challenging is your location. Whereas many practices, including some ambulatory services, have the equipment necessary to perform radiographs and ultrasounds, CT and MRI machines are less widely available. Unfortunately, depending on where you are located, the nearest facility might not be near at all, especially if you are looking for a facility with equipment to accommodate large animal species.

In addition to the factors above, a sanctuary’s access to advanced imaging might be limited due to financial constraints. While costs for diagnostic imaging vary state by state and even practice to practice, having a CT performed is sure to cost quite a bit more than a traditional radiograph or ultrasound, and an MRI typically costs even more than a CT. It’s important to budget for the veterinary care of your residents, but it’s also reasonable to have a discussion with your veterinarian about why they recommend advanced imaging over other techniques. While there may be times when advanced imaging is strongly recommended (and in some cases may be the only way to make a definitive diagnosis), there may also be times when it is reasonable to pursue less expensive radiographs and/or ultrasound to see if these give your veterinarian the information they need. Your veterinarian will be best able to advise you.

Computed Tomography (CT)

As with radiography, CT uses X-rays, but instead of using a stationary X-ray beam, the beam is quickly rotated around the body. Oftentimes, the process looks similar to when it is performed on a human, especially when smaller species are being scanned – the patient is placed on a special table that moves them into the machine while the X-ray tube rotates around them. While large animal species are sometimes scanned in this way, some facilities have machines that allow the patient to be scanned while standing. Special digital X-ray detectors collect X-rays as they exit the body and transmit them to a computer, which creates a detailed two-dimensional image every time the X-ray source completes a full rotation around the patient. These cross-sectional images are often described as “slices.” The process is repeated until the desired number of image slices are collected. Images can be displayed individually, or the computer can stack them to produce a three-dimensional digital image.

CT produces more detailed images than radiographs and is especially useful when areas with complex anatomy need to be evaluated. CT can be used to evaluate both bone and soft tissue structures and is considered one of the best diagnostic tools to assess certain parts of the body (such as the skull, chest, and abdomen). However, as mentioned above, various factors may make it difficult or even impossible to have a CT performed on certain residents.

Your veterinarian may recommend a CT when more detail is needed than what radiographs and/or ultrasound can provide. This may include, but is not limited to, the following:

- To diagnose certain cancers and to accurately identify tumor margins

- To diagnose abnormalities of blood vessels

- To diagnose certain musculoskeletal disorders

- To evaluate the head (including the skull, sinuses, and external and middle ear)

Because movement will negatively affect image quality, it is important that the patient remain still during the scan. As a result, CT scans are most often done with the patient anesthetized (however, machines designed to scan a standing horse allow for the patient to be sedated). Depending on the health status of the individual, anesthesia may not be advised. Your veterinarian will be able to explain the benefits of having a CT performed and the risks associated with anesthesia for the procedure. Because the scan itself is fairly rapid, in some cases, an individual may be able to be heavily sedated instead of anesthetized, but this may result in poorer-quality images. If the risk of anesthesia is too great and the procedure cannot be performed while the patient is sedated, your veterinarian may recommend performing radiographs and/or ultrasound instead of CT, even though they won’t provide the same level of detail.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRI is considered the most advanced imaging tool available in veterinary medicine. Like CT, magnetic resonance imaging produces cross-sectional image slices and can create a detailed three-dimensional image. However, unlike CT and radiography, MRI scanners do not use ionizing radiation. Instead, they use a powerful magnet and radio waves. Traditional MRI scanners are large tube-shaped chambers. The patient lies on a special table that moves them into the electromagnetic chamber, where they are pulsed with radio waves. These radio waves cause the body to emit radio frequency waves that can be detected and converted into images by a computer. As with CT scanners, there are also MRI scanners designed for horses that allow the patient to be imaged while standing. Currently, MRI imaging of large animal species is limited to the head and limbs.

MRI imaging is especially useful for imaging soft tissue structures, providing a level of detail that other types of imaging, including CT, do not. This allows veterinarians to visualize soft tissue structures that may be indistinguishable when using other imaging techniques. MRI can also reveal subtle abnormalities that would not be apparent using other techniques. It is considered the gold standard for examining the brain and spine.

Your veterinarian may recommend an MRI when detailed evaluation of soft tissue structures is required and is beyond what other diagnostic imaging can provide. This may include, but is not limited to, the following:

- To diagnose diseases of the brain

- To diagnose diseases of the spine

- To diagnose disorders of the inner ear

- To diagnose disorders of the eye

- To diagnose the cause of chronic lameness when other diagnostic procedures have been inconclusive

Though technological advances have reduced the amount of time it takes for MR images to be acquired, MRI continues to take longer than CT. As with radiography and CT, movement will affect the quality of the images, so patients must remain still. Therefore, with the exception of large animals being scanned while standing, general anesthesia is usually necessary.

Diagnostic imaging can play an important role in disease diagnosis and prognosis. While we hope this resource has given you a basic understanding of how this tool is used, your veterinarian will be your best resource when it comes to assessing your residents’ health, recommending the most appropriate diagnostics, and making sense of results. To learn more about other diagnostic tools your veterinarian may recommend, be sure to check out other resources in this series.

SOURCES:

X-Rays | Johns Hopkins Medicine

Imaging Service | Cornell University College Of Veterinary Medicine

ACVR’s Radiation Safety Statement | American College Of Veterinary Radiology

Ultrasound | American College Of Veterinary Radiology

Ultrasonography (US) | University Of Florida Large Animal Hospital

Ultrasound | University Of California, Davis, Veterinary Medicine

Large Animal Ultrasound | Texas A&M University Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital

Computed Tomography (CT) | National Institute Of Biomedical Imaging And Bioengineering

Computed Tomography (CT) | University Of California, Davis, Veterinary Medicine

Computed Tomography Applications in Veterinary Medicine | Craig Long, DVM, DACVR

High-Definition Computed Tomography (CT) | Virginia Tech Marion Dupont Scott Equine Medical Center

Computed Tomography (CT) | University Of California, Davis, Veterinary Medicine

Computed Tomography In Animals | Merck Veterinary Manual

Computed Tomography | University Of Florida Large Animal Hospital

Magnetic Resonance Imaging | Texas A&M University Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) | Penn Vet

Magnetic Resonance Imaging | University Of Florida Large Animal Hospital Magnetic Resonance Imaging In Animals | Merck Veterinary Manual

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) | University Of California, Davis, Veterinary Medicine

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) | Johns Hopkins Medicine Diagnostic Imaging | University Of Wisconsin Veterinary Care

Large Animal Ultrasound | University Of California, Davis, Veterinary Medicine (Non-Compassionate Source)

Imaging Techniques In Veterinary Medicine Part II: Computed Tomography, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Nuclear Medicine | Adelaide Greco a, Leonardo Meomartino, Giacomo Gnudi, Arturo Brunetti, Mauro Di Giancamillo (Non-Compassionate Source)

Non-Compassionate Source?

If a source includes the (Non-Compassionate Source) tag, it means that we do not endorse that particular source’s views about animals, even if some of their insights are valuable from a care perspective. See a more detailed explanation here.