Veterinary Review Initiative

This resource, which is an excerpt from our Basic Sheep And Goat Care Part 1 course, was reviewed for accuracy and clarity by a qualified Doctor of Veterinary Medicine with farmed animal sanctuaryAn animal sanctuary that primarily cares for rescued animals that were farmed by humans. experience in January 2022 as part of a larger review of the diet section of the course. Read about our Veterinary Review Initiative here!

Making It Work For CowsWhile "cows" can be defined to refer exclusively to female cattle, at The Open Sanctuary Project we refer to domesticated cattle of all ages and sexes as "cows."

While the following resource was written and reviewed with sheep and goats in mind, almost all of the sources we used to create the original were focused on ruminants, generally. In order to make this excerpt work for cows as well, all we needed to do was swap out a few instances of “sheep and goats” for the broader “ruminants” with one exception – since the original mentioned the quantity of gas produced by sheep and goats, we added information about the quantity of gas produced by mature cows, pulling that information from the same source we used for the sheep and goat information.

If you care for ruminants, such as sheep, goats, or cows, it’s important to have a basic understanding of how their digestive tract functions since it is very different from that of a monogastric animal (such as humans, pigs, or dogs). A ruminant’s complex digestive system allows them to efficiently digest and utilize high-roughage foods, such as forages, that are primarily composed of cellulose. Ruminants eat quickly, and rather than breaking down food by thoroughly chewing it before swallowing, ingested food goes through the process of rumination. Rumination mostly occurs during periods of rest, meaning ruminants will eat large portions of forage and then work on mechanically breaking it down when they are relaxing – food matter is regurgitated, re-chewed, and then swallowed again to be further digested (this is often called “chewing cudFood matter that returns from the first stomach compartment back to the mouth for further chewing”).

The Ruminant Stomach

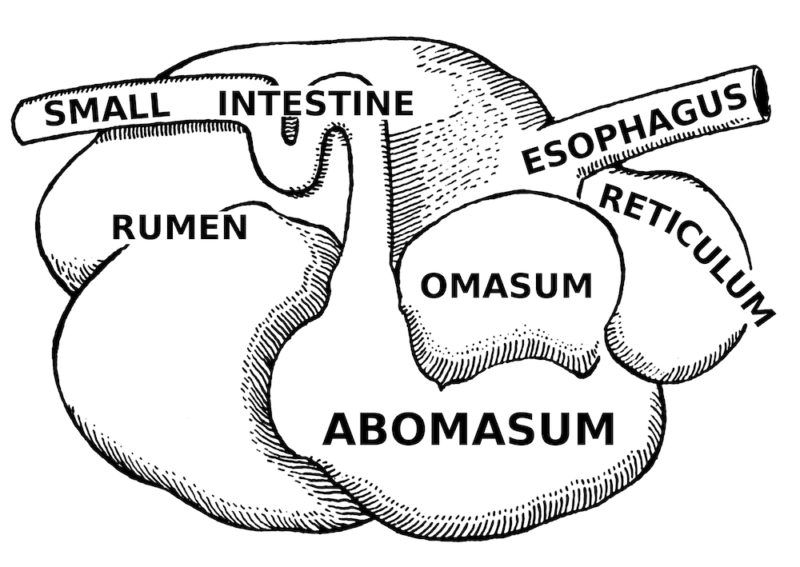

Ruminants are sometimes mistakenly described as having four stomachs, but in reality, they have one stomach with four compartments – the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum. The ruminant stomach takes up nearly 75% of the abdominal cavity, filling almost the entire left side and extending into a significant portion of the right side.

The rumen is the largest compartment and is essentially a fermentation vat. The reticulum is closely associated with the rumen, and food moves freely between the two – together, they are referred to as the reticulorumen. It is in the reticulorumen that ingested food undergoes microbial digestion (fermentation). The liquid portion of ingested food moves through the reticulorumen quickly, but the solid portion will typically stay in the rumen for up to 48 hours while rumen microbes break it down. Fifty to sixty percent of the starch and digestible sugars consumed are digested in the rumen. Microbes break down tough plant matter and form volatile fatty acids (VFAs), which account for over 70% of a ruminant’s supply of energy. These microbes can also utilize non-protein nitrogen sources to synthesize protein and can synthesize B vitamins and vitamin K.

According to information from Colorado State University,

“Fermentation is supported by a rich and dense collection of microbes. Each milliliter of rumen content contains roughly 10 to 50 billion bacteria, 1 million protozoa and variable numbers of yeasts and fungi…. Fermentative microbes interact and support one another in a complex food web, with the waste products of some species serving as nutrients for other species.”

Abrupt changes in diet can affect this complex web, and if large amounts of soluble carbohydrates are consumed, such as in the form of concentrates, rumen pH can drop (normal pH is 6-7), destroying many microbial species, slowing motility, and causing serious issues.

The fermentation process produces a large quantity of gas – approximately 5 liters per hour for sheep and goats and 30-50 liters per hour for adult cows – and this rises to the top of the rumen. This gas must be released regularly through eructation (burping). Anything that interferes with a ruminant’s ability to burp and release this gas can be life-threatening.

As the ingested food moves between the rumen and reticulum, small food particles are collected in the reticulum and moved into the omasum, while large particles continue to break down in the rumen. Not much digestion occurs in the omasum. Here, water is absorbed from ingested food, and the remaining food then moves into the abomasum, or “true stomach”. In the abomasum, hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes continue to break down food before it passes into the intestines, where further nutrient absorption occurs.

Babies Are Different!

It’s important to note that when ruminants are born, their digestive tract functions like that of a monogastric animal for their first month of life. Their forestomachs are not fully developed, and if milk were to enter the rumen, it would rot rather than ferment. To prevent this from happening, when a baby suckles, their esophageal groove closes, allowing milk to bypass the reticulorumen. (To learn more about what to feed baby ruminants, check out our resources on calf, lamb, and kid care!)

Now that you’ve got a basic understanding of ruminant digestion, be sure to check out our resources on sheep, goat, and cow diets, if you haven’t already, so that you can provide your ruminant residents with a diet that supports healthy rumen function!

SOURCES:

Digestive Physiology of Herbivores | VIVO Pathophysiology

Fermentation Microbiology And Ecology | VIVO Pathophysiology

Rumen Physiology and Rumination | VIVO Pathophysiology

Understanding the Ruminant Animal Digestive System | Mississippi State University Extension (Non-Compassionate Source)

The Amazing Ruminant | UGA Forage Extension Team (Non-Compassionate Source)

Nutrient Absorption And Utilization In Ruminants | VIVO Pathophysiology (Non-Compassionate Source)

Non-Compassionate Source?

If a source includes the (Non-Compassionate Source) tag, it means that we do not endorse that particular source’s views about animals, even if some of their insights are valuable from a care perspective. See a more detailed explanation here.