We all want the animals in our care to be happy and healthy. Unfortunately, there will likely be times when a sanctuary resident isn’t feeling their best. Abnormal behavior is generally a sign that something might be amiss with a resident. Have you ever noticed a horse resident biting a fence post and sucking in the air? Or a parrot resident plucking out their feathers? Maybe a sheep resident eating another sheep resident’s wool? These are just a few examples of abnormal behaviors. Often, these behaviors can indicate underlying physical illness or psychological distress. It may be in response to something about their environment or having their natural behaviors thwarted, feeling conflicted between two different behaviors, or due to an underlying physical or mental illness, in which case prompt veterinary care is vital. Either way, abnormal behaviors should be a red flag to caregivers that something is amiss. In this resource, we will define types of abnormal behaviors, discuss possible contributing factors, and look at some species-specific examples for you to be on the lookout for at your animal sanctuary.

What Is Normal?

The first step in identifying abnormal behaviors is being familiar with what behaviors are normal for the species (and individual!) For this, it may be helpful to research and build a behavioral repertoire of normal behaviors for each species. This is like an ethogram, but it may only include some of their behaviors and is generally used in observational behavior studies. This will not only help you identify abnormal behaviors but also help you better understand when abnormal behavior is caused by a normal behavior being frustrated. Learning to identify normal and abnormal behavior can also help you spot injury and illness in addition.

What Is Abnormal?

You probably have an idea of how you would define abnormal behavior. However, in terms of having a shared language with others and understanding the terms and contexts surrounding abnormal behavior in residents, it can be helpful to see how it is explicitly defined in terms of nonhuman animals (usually living in human-managed environments). Let’s look at a few of these:

“Abnormal behaviour is defined as an untypical reaction to a particular combination of motivational factors and stimuli.”

“Abnormal behaviors are individual and social actions that are disturbing, destructive, or detrimental to the physiological, psychological, and social well-being of a mouse and its [sic] cagemates. They are behaviors that differ in pattern, frequency, or context from that shown by most members of a species. “

“Behaviors can be considered abnormal if they are qualitatively different (i.e., occur in captivity but not typically in the natural setting) or quantitatively different (i.e., occur significantly more or significantly less than what is observed in the natural setting)”

Health And Abnormal Behaviors

While many abnormal behaviors stem from inappropriate environmental factors, they can also indicate underlying illness or injury. When abnormal behavior is observed, assessing that individual’s health is essential. Many health issues can be more easily resolved when treated early on, possibly reducing any pain or discomfort a resident may be experiencing. If a health check rules out injury or illness as a factor, start looking towards environmental factors as possible causes.

Maladaptive Versus Malfunctional Behavior

Before we look more specifically at different abnormal behaviors, let’s define two categories into which abnormal behaviors may fall:

Maladaptive Behaviors

Maladaptive behaviors are performed by a “normal” animal in an abnormal environment. These behaviors would often make sense or be useful in a “normal” environment but do not make sense in the current environment (for example, it makes sense for a cowWhile "cow" can be defined to refer exclusively to female cattle, at The Open Sanctuary Project we refer to domesticated cattle of all ages and sexes as "cows." to roll their tongue to grasp grasses while grazing, but this behavior doesn’t make sense when no food is present.)

Example

Norman is a healthy, weaned calf that was recently rescued. Previously, he lived with his mother and a small herd. Sadly, he lost his mother, and the farmer was persuaded to give him to a local animal sanctuary. When he arrives, he receives a health check, and the vet determines he is physically healthy, to the relief of his caregivers. Of course, he is kept in quarantineThe policy or space in which an individual is separately housed away from others as a preventative measure to protect other residents from potentially contagious health conditions, such as in the case of new residents or residents who may have been exposed to certain diseases. to be safe, as some illnesses can show up later. The quarantine area is on the other side of the sanctuary, away from the cow living space. From where he is, he cannot see the other cow residents. He is kept indoors in a smaller living spaceThe indoor or outdoor area where an animal resident lives, eats, and rests. and receives grass hay in the morning. The week he is supposed to join Bell and her older calf Trudie, a storm damages some of the fencings. This extends the time that Norman is isolated from other cow residents. During this time, caregivers notice that he starts exhibiting tongue-rolling behavior. Tongue-rolling behavior is when a cow flicks their tongue out or around and repeatedly rolls it back inside their mouth. This is repetitive, so not just a normal lick of the nose. This abnormal behavior is sadly seen in calves exploited for veal. The stress of separation, isolationIn medical and health-related circumstances, isolation represents the act or policy of separating an individual with a contagious health condition from other residents in order to prevent the spread of disease. In non-medical circumstances, isolation represents the act of preventing an individual from being near their companions due to forced separation. Forcibly isolating an individual to live alone and apart from their companions can result in boredom, loneliness, anxiety, and distress., improper diet, and an inability to exhibit other normal behaviors can all factor into developing this maladaptive behavior.

In this situation, Norman is experiencing a lot of environmental stressors. He cannot participate in normal social and foraging behaviors, and his environment lacks enriching experiences or aspects. Confinement and unnatural foraging behavior, in particular, has been studied as a factor in the prevalence of tongue-rolling behavior in cowsWhile "cows" can be defined to refer exclusively to female cattle, at The Open Sanctuary Project we refer to domesticated cattle of all ages and sexes as "cows.". Diets that do not support the normal foraging behaviors of cows can cause frustration, resulting in cows performing tongue rolling in an attempt to adapt to an inadequate environmental factor. A cow will spend more than half their day engaging in foraging-related behaviors. During this time, their tongue is in near-constant motion. If a cow is in an environment where they are only fed once or twice and in amounts that do not support normal foraging activity, a maladaptive behavior, such as tongue rolling, may develop.

Luckily, some of these behaviors can be reduced or eliminated simply by removing the environmental stressor. In Norman’s case, caregivers should address this by ensuring that Norman has plenty of hay throughout the day to support normal eating behaviors. Additional changes could include temporarily moving Bell and Trudie to a closer living space where Norman can have visual contact with them until he can join them. Ensuring Norman has adequate room to move about and explore can help, as can adding different types of enrichment to provide stimulation while he is housed separately.

Malfunctional Behaviors

Malfunctional behaviors differ from maladaptive behavior in that they involve an individual with some aspect of abnormal physiology, brain development, or neurochemistry brought about by genetics or living in a captive environment. The environment isn’t necessarily the issue at this point, as the behaviors may be present in a poor or good environment. Sometimes captive environments that cause maladaptive behaviors can change an individual’s brain over time, causing them to behave abnormally in a malfunctional sense.

Example

Winter is a 2-year-old llama resident who came to the sanctuary fairly recently. He lost his mother soon after he was born and was bottle-fed by the human family that cared for him. The kids enjoyed bottle-feeding and playing with him so much that the parents allowed them to continue feeding him until he was around a year old. Winter lived alone, next to a herd of goats in a neighboring field during this time. When he was about a year old, he started rearing up and becoming pushy with the family members. No one thought anything of it and interpreted it as him “playing games.” Then he started charging them, spitting and even slamming against the gate multiple times when a family member rushed out of it after being charged by him. This happened when no one did anything threatening or different than they ever had. His behaviors escalated until the family didn’t feel safe with him. Winter did not learn natural llama behavior; his human family was all he knew. His psychological development was interrupted by being raised by a human family. He soon came to live at the sanctuary near other llamas, where care staff, experienced in camelid care, created a care plan alongside their veterinarian and camelid behaviorist to provide the best care possible. In this case, Winter’s behaviors were not just those of a “normal” llama trying to cope in an abnormal environment. Winter’s psychological development was abnormal and altered his physiology. His behaviors are malfunctional as opposed to maladaptive.

Genetics can also play a factor in the development of malfunctional behaviors. In its simplest definition, malfunctional behaviors are abnormal behaviors performed by individuals with “abnormal” physiology of some sort.

Now that we have defined maladaptive and malfunctional behaviors, let’s look at a few other behavioral terms that might come in handy:

Abnormal Repetitive Behaviors

Abnormal repetitive behaviors can be broken down into two categories: stereotypies and compulsive behaviors (often considered a disorder):

Stereotypies

Not All Abnormal Behaviors Are Stereotypies

Although the word stereotypy is often used frequently to refer to abnormal behaviors, it is important to understand that abnormal behavior can fall outside the parameters of stereotypical behaviors. Abnormal behaviors are those that fall outside the normal behavioral repertoire or are excessive, absent, or out-of-context. Stereotypies and compulsive behaviors are a category of abnormal behaviors, specifically repetitive ones.

Stereotypies, or stereotypical behaviors, are generally defined as repetitive behaviors that are not functional or have no purpose. When an individual is struggling to cope in a human-controlled environment that is not meeting their needs, they may develop stereotypic behaviors such as pacing, weaving, plucking feathers or biting themselves, chewing on fencing or gates, cribbing (Cribbing is a stereotypy seen in horses when an individual bites onto a surface like a post or a fence with their front teeth and flexes the muscles in their neck while pulling back which generally produces a grunting sound), rubbing one’s head or another body part on various surfaces, rolling eyes, biting or other harmful behaviors directed at others or themselves, or tongue-rolling.

The main thing to note about stereotypies is how unvarying they are in their particular patterns. Any sign of repetitive behavior that doesn’t serve a purpose should serve as a red flag. Caregivers should take a closer look and try and determine what might be causing an individual to struggle to cope in their environment. A physical health checkThe Open Sanctuary Project uses the term "health check" to describe health evaluations performed by caregivers who are not licensed veterinarians. While regular health checks are an important part of animal care, they are not meant to be a replacement for a physical exam performed by a licensed veterinarian. is important, as well as determining what possible environmental or other management factors might contribute to their stress.

Example

Nisbet is a rabbit resident whose living area consists of a standard rabbitUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated rabbit breeds, not wild rabbits, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource. cage, bedding, a waterer, all the hay she wants, daily fresh leafy greens, a cardboard house, and chew toys that are changed each week. She also has a little ramp leading out into a 5 x 5 pen area with a tunnel, a blanket, and a ball. Although Nisbet can be seen eating and drinking regularly, using her tunnel, and occasionally chewing on a toy, she also spends a significant amount of time in the corner of her living area frantically digging at the floor. This behavior had been going on for weeks. Her caregivers are concerned. It appears to them that Nisbet’s environment is lacking and not meeting her needs. After a health check to ensure there isn’t anything physically wrong, her caregivers sit down and list what might be negatively affecting Nisbet. They noted that rabbitsUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated rabbit breeds, not wild rabbits, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource. are natural diggers and dig and make their home in burrows and that rabbits are social animals and ideally should have a companion. These were two areas lacking for Nisbet and could contribute to her stress and the stereotypy of corner-scratching. Nisbet is a normal rabbit in an inadequate environment. Once care staff provided Nisbet with a special digging box and introduced another rabbit resident to a living space near her (hoping to join their living spaces), the behavior was significantly reduced. It was something they only ever observed a few times in the following months.

Stereotypies can sometimes be stopped by making simple changes to a resident’s environment or routine or by addressing health issues. Sadly, this isn’t always the case. Sometimes they become ingrained, even changing an individual’s physiology, and a resident may continue to exhibit behaviors despite changes. However, changing contributing factors can often lessen the frequency or intensity and improve overall well-being. The best thing you can do as a caregiverSomeone who provides daily care, specifically for animal residents at an animal sanctuary, shelter, or rescue. is set them up for success and reduce the likelihood of someone developing these behaviors.

Compulsive Behaviors

Compulsive behaviors are also abnormal repetitive behaviors. These behaviors may vary in their presentation and can be thought of as stereotypies that stuck even after changing the environment. When a stereotypy becomes disconnected from the original causal factor, it might be considered a compulsive behavior.

Example

Hessia, an older horse resident, experiences frustration in the morning while waiting for breakfast. She is excited and highly motivated to eat her morning meal. She begins pawing at the ground in the mornings but stops when her food arrives. This behavior becomes repetitive. It is an attempt to cope with the frustration of not being able to eat when she wants to. However, this behavior ceases once she has been turned out to pasture. That is an example of stereotypy. Suppose Hessia had continued to paw the ground after being given access to the pasture. This could be considered a compulsive behavior as it is no longer simply connected to a particular environmental frustration.

Redirected Behaviors

Some observed abnormal behaviors may be redirected behaviors. Redirected behaviors occur when an individual targets an inappropriate object or person when they cannot direct that behavior to the actual target they are motivated to act upon.

Example

Chen, a pig resident, hasn’t been able to go outside for the past few days due to a blizzard. Normally Chen is eager to explore their outdoor living space (exploration is a natural behavior in pigs) and enjoys rooting around. This blizzard has limited Chen’s ability to explore as he doesn’t have the usual space and dynamic environment to engage. His indoor living space consists of an 8 x10 area that he shares with Becca, with an automatic waterer, rubber food bowls, and rubber mats to lay on. Chen wants to root around in the dirt, but he can’t. In his frustration, Chen has redirected his desire to root around in the dirt to rooting around and manipulating his feces. Chen is motivated to carry out normal, healthy behavior in this case. Environmental factors thwart Chen’s attempt to carry out a highly motivated natural behavior, so in his frustration, he is carrying out a naturally motivated behavior on an inappropriate object. Providing straw for bedding would allow him to root around, and providing enrichment, even quiet instrumental music in the background, could positively affect Chen and reduce or eliminate this behavior. Redirected behaviors can also often be witnessed when an individual lashes out at someone who has nothing to do with who or what they are actually upset by.

Displacement Behaviors

Displacement behaviors may appear out of context in a situation. Situations where an individual feels conflicted between two competing motivations or when an individual is frustrated by an inability to perform a desired behavior, can lead to a displacement behavior.

Example

Plucky, a duck resident, is motivated to approach a pinwheel outside her outdoor living space. She is also nervous about approaching the pinwheel and is motivated to walk safely inside the door to her indoor living space. You can see this as she focuses on the pinwheel and makes toward it, then stops and turns around to go back inside. Instead of going forward to explore or go back to safety, Plucky stops and starts doing something unrelated, in this case, preening.

This is an example of displacement behavior because the behavior, preening, has nothing to do with the motivations of the individual and is out of context in this situation.

Note that this isn’t an example of stereotypy (stereotypical behavior). Still, preening can be a stereotypical behavior if an individual repeats the same behavior frequently, possibly injuring themselves in the process, indicating that the “preening” behavior is not serving a function (i.e., cleaning their feathers.)

Now that we have covered some basic concepts of abnormal behavior, let us look at factors that may contribute to the development of such behaviors:

Identifying Contributing Factors To Abnormal Behaviors

- Space – A lack of adequate space in a living space where residents can move freely and exhibit natural movements and behaviors can negatively affect residents.

- Social – Isolation, overcrowding, and contentious social groups can be contributing factors.

- Dietary – Diets that lack the appropriate nutrients, “bulk,” and amount can be a causal factor in developing abnormal behaviors. Additional dietary factors include the number of times an individual is fed and whether their diet allows them to perform natural behaviors for an appropriate amount of time. For example, concentrate diets are typically gobbled up quickly, leaving residents unable to carry out their normal foraging behavior that may naturally take them many hours over a day.

- Health – Many underlying health conditions can cause an individual to exhibit abnormal behaviors. If you see an individual carrying out abnormal behaviors without an immediately obvious environmental cause, do a thorough health check. In either case, at least do a brief check for any obvious signs of illness or injury.

- Bare Environment – Environments lacking appropriate substrate, bedding, resting areas, engaging areas, or activities can significantly increase the risk of an individual struggling to cope with their environment, potentially leading to abnormal behaviors and most certainly leading to poor emotional, mental, and aspects of physical welfare.

- Lack Of Stimulation – All residents should have dynamic, engaging environments and activities to explore and participate in. Enrichment is a vital part of resident care. Many forms of enrichment can help ensure residents are appropriately and adequately stimulated. Without stimulating experiences, individuals can become bored and frustrated, increasing the risk of developing abnormal behaviors.

- Lack Of Control – Lack of control over environmental stressors (loud noises, inability to get away, unable to remove themselves from stressful group dynamics, inability to hide visually from humans and other residents, not being able to choose when they eat).

- History – A resident may have previously developed maladaptive behaviors in another environment that may have affected their physiology. Hence, these behaviors are now malfunctional, which may persist even when the causal factors are removed. However, removal often results in a reduction of these behaviors and is still better for the individual.

- Genetics – Genetics can play a role in the development of stereotypies. In some cases, certain breeds are more prone to certain abnormal behaviors than others. The health and stress of the mother while pregnant can increase the risk of their offspring developing certain behavioral traits.

- Maternal Deprivation And Early Life Experiences – The absence of normal maternal care in mammals may lead to abnormal oral behaviors. A lack of normal parental presence and care may affect how individuals manage stressors.

- Mimicry – There is some evidence in certain species that an individual may learn a stereotypy by observing a herd or flock mate.

- Temperament – Everyone is an individual. Someone with a particular temperament may be more prone to developing certain abnormal behaviors. Suppose you have an outgoing, energetic resident. In that case, they may struggle more quickly or intensely with confinement or isolation. In contrast, someone who is timid may struggle when living with too many residents for the space or with a lack of control over being able to remove themselves from unwanted interactions.

Now that we have defined certain abnormal behaviors and reviewed contributing factors in developing these behaviors, let’s consider questions you can ask yourself when trying to determine the normality/abnormality of a witnessed behavior:

Questions To Ask

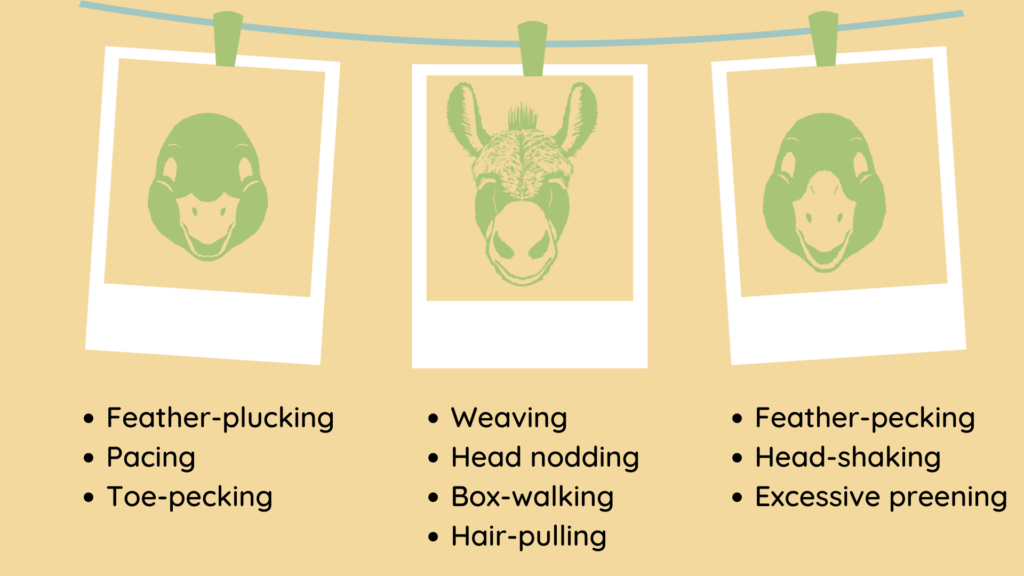

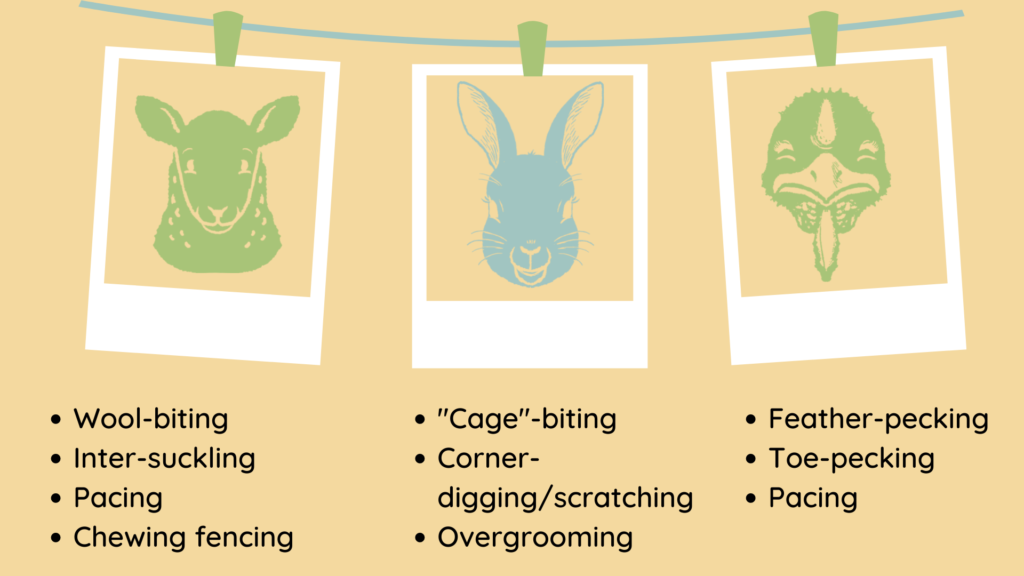

While this is far from exhaustive, a list of species-specific examples of abnormal behaviors is below. This is just to give you an idea of a few things to watch out for in resident populations.

What You Can Do

While we are covering ways to address, reduce, and lower the risk of residents developing abnormal behaviors more in-depth in another resource, we want to leave you with some brief tips on promoting well-being among resident populations. Content, happy, healthy residents are much less likely to develop abnormal behaviors.

- When providing diets to residents, offer appropriate foods, meet their nutritional needs, allow and encourage natural eating and drinking behavior, and space meals throughout the day when possible and appropriate.

- Living spaces should provide comfortable shelter that allows free movement and the ability to distance oneself from social conflict. Additionally, try and make the environments centered on the particular species (while also considering the individual) and provide appropriate topography and environmental features that encourage residents to engage with their environment.

- Develop an enrichment schedule! Integrate physical/structural, social, nutritional, sensory, and cognitive enrichment into their daily lives. Environmental enrichment has been shown to improve well-being over and over again.

- Whenever possible, allow residents choice. Allowing residents to remove themselves behind a visual barrier, respecting their desire to walk away, or offering different enrichment and “asking” what they prefer can make a tremendous difference in promoting well-being.

- Perform regular health checks. This cannot be overstated. It is vital that in addition to a daily once over and keeping a general eye out, thorough health checks take place regularly. This will help you catch health issues early.

- Ensure appropriate social groupings. Avoid isolating social individuals whenever possible. Avoid overcrowding and pay close attention to group dynamics to ensure harmonious relations.

- Treat everyone as the individual they are and develop care plans that accommodate their differences and needs.

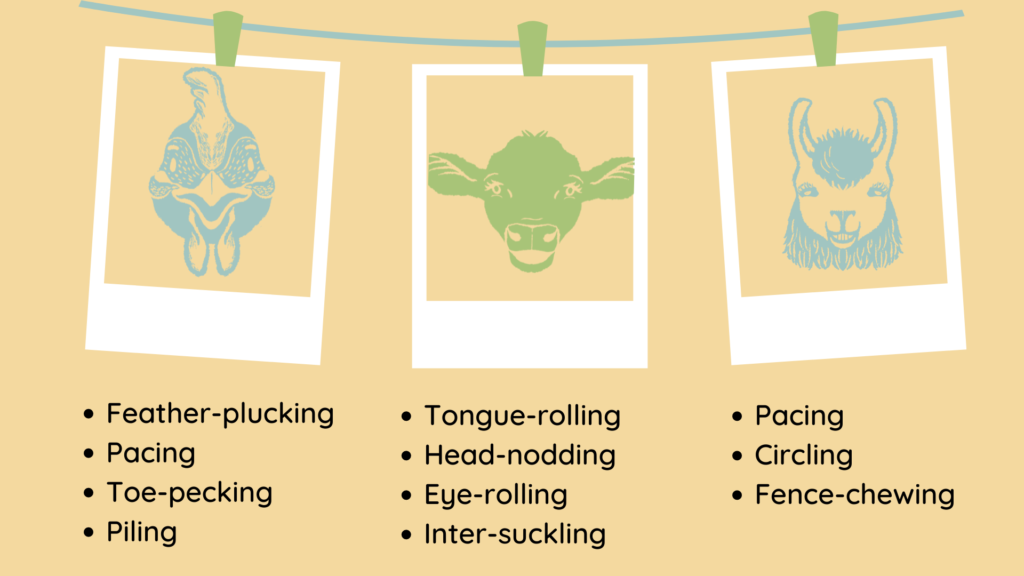

Commonly Observed Abnormal Behaviors By Species

Camelids (Alpacas and Llamas) – Pacing; circling behavior; chewing

Chickens – Feather plucking; redirected preening; piling; spot-pecking; toe-pecking; cannibalism; pacing; sham dust-bathing

Cows – Tongue-rolling;, eye-rolling; self, cross, or inter-suckling; bar-biting; licking or eating random objects; coprophagy; head-rubbing; head-tossing; calf-stealing

Donkeys – Head-nodding; hair-pulling; box-walking; weaving

Ducks – Feather-plucking, head-shaking; pacing

Geese – Feather-pecking; head-shaking; excessive preening

Goats – Self-suckling; inter-suckling; wrapping tongue around bars or other objects; licking walls; chewing on fixtures

Horses – Cribbing; windsucking; wood-chewing; head-shaking; stall-kicking; pica; self-mutilation; pawing; coprophagia (eating feces though this is normal in young foals); rejecting foals; weaving; box-walking

Pigs – belly-nosing; biting and chewing on the ears or tail of group mate; bar-biting; sham-eating; head-shaking; pacing; nose-rubbing; infanticide; cannibalism

Rabbits – Corner-scratching; cage-biting; circling; over-grooming

Sheep – Wool-biting; lamb-stealing; inter-suckling; head-butting; pacing; pawing; nosing fixtures; chewing fixtures

Turkeys – Feather-pecking; toe-pecking; pacing; piling; cannibalism

* Excessive, extreme, or inappropriate behaviors towards others can be abnormal and seen across species. We believe the word “aggressive” or “aggression” is overused and can affect the type of care an individual receives, often unjustly labeling them as “bad.” Language matters. Generally speaking, we believe “confrontationalBehaviors such as chasing, cornering, biting, kicking, problematic mounting, or otherwise engaging in consistent behavior that may cause mental or physical discomfort or injury to another individual, or using these behaviors to block an individual's access to resources such as food, water, shade, shelter, or other residents.” is a better term to describe an individual’s normal behavior in response to perceived threats, territorial disputes, and social relationship behaviors. However, there is room for the term aggressive and aggression. There are instances where a physiological or psychological factor causes frequent or especially extreme or misdirected or inappropriate (to the situation) behaviors that may more appropriately be termed “aggressive behaviors.” In these cases, the aim isn’t to label the individual in a negative light. Instead, it is to draw attention to a severe physiological or psychological issue that requires immediate attention to resolve. Normal confrontational behaviors serve a function. The abnormal “aggression” is different as it may be extreme, excessive, inappropriate in the context, or persistent.

We hope this has been a helpful introduction to abnormal behaviors in resident populations. Remember, before identifying abnormal behavior, you must know what is normal! And, when in doubt, speak with an experienced veterinarian. Stay tuned for an upcoming resource on preventing and managing abnormal behaviors.

10 Factors Contributing To Abnormal Behavior Infographic

10 Factors by Amber D Barnes

SOURCES:

Abnormal Behaviour | British Veterinary Association

Stereotypic Behavior And Compulsive Disorder | Vetfolio

Rabbit Behavior | Veterinary Key

Is My Rabbit Suffering From Stress? | RSPCA

Glossary Of Behavioral Terms | Merck Manual Veterinary Manual (Non-Compassionate Source)

Stereotypies And Other Abnormal Repetitive Behaviors: Potential Impact On Validity, Reliability, And Replicability Of Scientific Outcomes | Institute For Laboratory Animal Research Journal (Non-Compassionate Source)

Animal Behaviour | Wild Welfare (Non-Compassionate Source)

The Use Of Positive Reinforcement Training To Reduce Stereotypic Behavior In Rhesus Macaques | Applied Animal Behavior Science (Non-Compassionate Source)

Stereotypic Behaviour In Captive Animals: Fundamentals And Implications For Welfare And Beyond | University Of Guelph (Non-Compassionate Source)

Replace the Pace: Stereotypy in ZooAn organization where animals, either rescued, bought, borrowed, or bred, are kept, typically for the benefit of human visitor interest. Animals | Experiment (Non-Compassionate Source)

South-American Camelidae (Alpacas, Guanacos And Vicuñas): Basic Activity Budgets | Conference: Proceedings Of The Ninth Annual Symposium On Zoo Research (Non-Compassionate Source)

Physiological Indicators And Production Performance Of Dairy Cows With Tongue Rolling Stereotyped Behavior | Frontiers In Veterinary Science (Non-Compassionate Source)

The Behaviour Of Sheep With Sheep Scab, Psoroptes Ovis Infestation | Veterinary Parasitology (Non-Compassionate Source)

Prevalence And Incidence Of Abnormal Behaviours In Individually Housed Sheep | Animals (Non-Compassionate Source)

Cognition And Behavior In Sheep Repetitively Inoculated With Aluminum Adjuvant-Containing Vaccines Or Aluminum Adjuvant Only | Journal Of Inorganic Biochemistry (Non-Compassionate Source)

Effects Of Dietary Fibre And Feeding Frequency On Wool Biting And Aggressive Behaviours In Housed Merino Sheep | Australian Journal Of Experiemental Agriculture (Non-Compassionate Source)

Level Of Stress In Relation To Emotional Reactivity Of Hens | Italian Journal Of Animal Science (Non-Compassionate Source)

Behavioral And Health Problems Of Poultry Related To Rearing Systems | Ankara Univ Vet Fak Derg (Non-Compassionate Source)

An Analysis Of Displacement Preening In The Domestic Fowl | Animal Behavior (Non-Compassionate Source)

Chapter 8: Animal Well-Being And Behavioral Needs On The Farm | Improving Animal Welfare: A Practical Approach (Non-Compassionate Source)

Homeostasis And Time Budgets | Animal Behavior (Non-Compassionate Source)

Play Behavior And Environmental Enrichment In Pigs | Wageningen University & Research (Non-Compassionate Source)

Omnivores Going Astray: A Review And New Synthesis Of Abnormal Behavior In Pigs And Laying Hens | Frontiers In Veterinary Science (Non-Compassionate Source)

Behavioral Problems Of Chickens | The Merck Veterinary Manual (Non-Compassionate Source)

Factors Influencing The Development Of Stereotypic And Redirected Behaviours In Young Horses: Findings Of A Four Year Prospective Epidemiological Study | Equine Veterinary Journal (Non-Compassionate Source)

Assessment Of Welfare In Pigs | Italian Journal Of Animal Science (Non-Compassionate Source)

Behavioral Problems Of Cattle | The Merck Veterinary Manual (Non-Compassionate Source)

Welfare Conditions Of Donkeys In Europe: Initial Outcomes From On-Farm Assessment | Animals (Non-Compassionate Source)

Abnormal Repetitive Behaviours In Captive Birds: A Tinbergian Review | Applied Animal Behavior Science (Non-Compassionate Source)

Water For Domestic Ducks: The Benefits And Challenges In Commercial Production | Frontiers In Animal Science (Non-Compassionate Source)

The Welfare of Animals In The TurkeyUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated turkey breeds, not wild turkeys, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource. Industry | Wellbeing International (Non-Compassionate Source)

Animal-Based Measures For The On-Farm Welfare Assessment Of Geese | Animals (Non-Compassionate Source)

Non-Compassionate Source?

If a source includes the (Non-Compassionate Source) tag, it means that we do not endorse that particular source’s views about animals, even if some of their insights are valuable from a care perspective. See a more detailed explanation here.