Reminder: We Aren’t Your Lawyer!

The Open Sanctuary Project is not a law firm and this resource is not a substitute for the services of an attorney. Accordingly, you should not construe any of the information presented as legal advice that is suitable to meet your particular situation or needs. Please review our disclaimer if you haven’t yet.

Resource Goals

- To gain a basic understanding of how code and common law systems operate;

- To learn about the difference between civil and criminal law processes within common law systems;

- To understand the gatekeeping mechanisms of courts of law;

- To understand some of the kinds of remedies that may be available through courts of law;

- To learn about the costs and benefits associated with the use of litigation to resolve conflicts;

- And to learn the basics of alternative dispute resolution.

Introduction

Conflict can arise in all walks of life; unfortunately, the animal sanctuary and rescue world is not immune to it. You might encounter conflict regarding questions of animal “ownership” in adoption contexts or in disputes over land boundaries. Or you might run into it when it comes to disputes over work, such as when you employ an independent contractor.

Your best defense to protecting your organization from legal liability is to think about problems you might encounter in advance and then to work with licensed professionals in your jurisdiction to do your due diligence and manage your liabilities. This may involve developing contracts for adoption or employment tailored to your organization, or doing land surveys to ensure you have all the information you need about your property. (Note that we have resources you can use as a starting point on all of the above, which are linked below in our sources!)

However, at some point in your sanctuary or rescue journey, even if you take precautions, you will likely encounter a conflict that is challenging to navigate without outside assistance. Sometimes, that outside assistance might involve using the legal system. This resource is meant to introduce you to some of the basic mechanisms the legal system offers for the “resolution” of conflict.

The Legal System Is Not Your Only Option!

While employing the legal system to resolve conflict is what most people probably consider the “go-to” when coping with difficult conflicts, it is not your only option. You can also explore options such as restorative and transformative justice frameworks. Check out our conflict support series here to learn more about this!

Litigation

When conflict rises to a level where one or more parties feel that outside intervention to resolve it is necessary, most people tend to think about litigation. Litigation is the process of using government-established courts to resolve the rights, claims, and liabilities of parties who are in conflict. The systems that governments use to govern their court systems can generally be divided into four categories:

- Common law;

- Civil or Code law;

- Religious law; and

- Customary law.

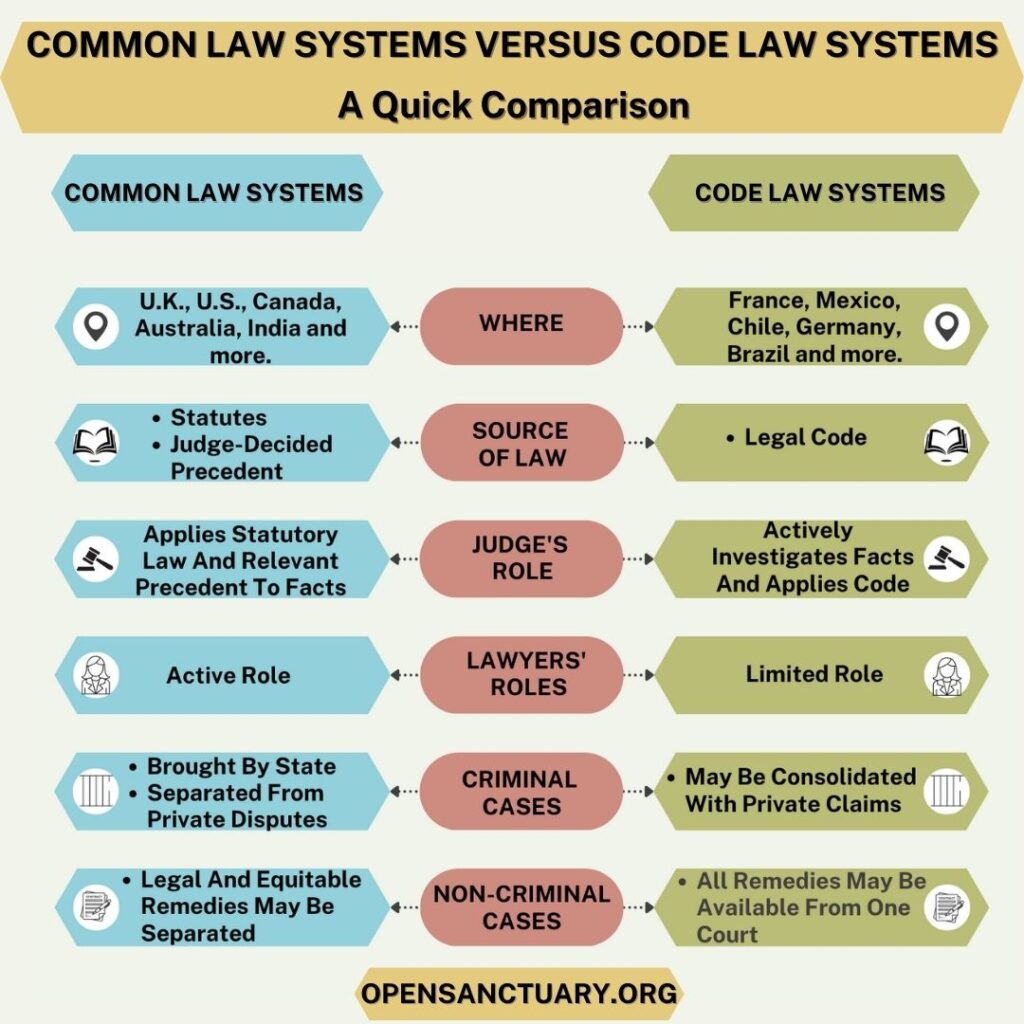

Some countries may use hybrid or combinations of these systems as well. Because common law probably applies to the largest number of people internationally, and civil or code law systems cover the largest land mass internationally, we will focus our discussion on those two systems.

A Note On Terminology

If you’re familiar with the term “civil law” in the context of common law systems, be aware that this term is distinct and separate from the larger systems of civil or code law. To avoid confusion in this resource, we will refer to the civil or code law system exclusively as “code law.” We’ll discuss the difference between civil and criminal courts under common law systems more below!

The United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, India and others have adopted what is known as a “common law” system, which derived from a tradition that developed in England in the Middle Ages and has spread to most countries that the British primarily colonized. The role of a jury (if used) is to decide on the facts of a case, while a judge then applies the law to those facts. The past decisions of courts are known as “precedents,” which, along with statutory law created by legislatures, are the primary means used to guide ongoing decision-making by courts. In this system, defense and prosecutorial attorneys actively participate in hearings and trials.

Countries like France, Germany, Mexico, Chile, Brazil and others have adopted code law, which is based on Roman legal traditions. Code law systems are seen in many countries colonized by the French, Germans and other mainland European countries. These countries have “codified” laws that specify all matters that can be brought before a court, the applicable procedure, and the appropriate “punishment” for each “offense.” In a code law system, a judge’s work has less impact on the ongoing development of the law than that of the decisions of legislators who draft the code. A judge plays more of an inquisitorial role and actively investigates the facts of a case, while prosecutors and defense attorneys play a more limited role.

Some jurisdictions operate under a hybrid of common and code law. These include one state in the U.S., Louisiana, and one in Canada, Quebec, based on their former governance by French colonizers. To learn more about the history of both common and code law systems, you can check out this resource! We have noted some differences between these systems, but they also have some important commonalities. We’ll discuss those a little bit more below! But first, let’s quickly clear up another important distinction…the difference between criminal and “civil” law cases under common law systems!

The Difference Between Criminal And Civil Law In Common Law Systems

Here’s a confusing fact. Within common law systems, there is generally a distinction drawn between criminal law and what’s known as civil law. Yes, we just discussed an entire system of law known as civil or code law! But that’s not what we’re talking about here! In this context, we want to clarify that the term “civil law” used within common law systems (such as those within the U.S., U.K., Canada, Australia and India) is quite distinct from the larger code law tradition described above.

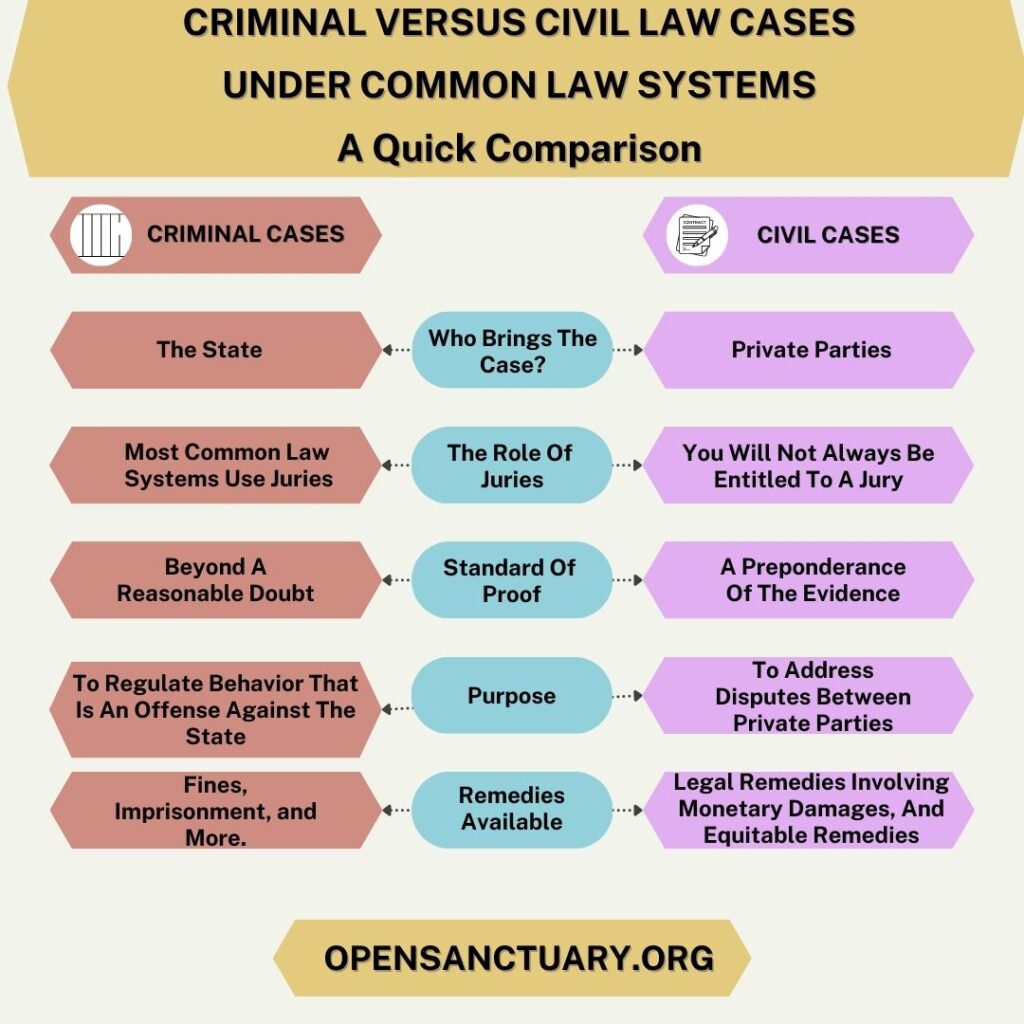

Criminal law and civil law differ concerning how cases are initiated (who may bring charges or file suit), how cases are decided (whether by a judge or a jury), what kinds of punishment or penalties may be imposed, what standards of proof must be met, and what legal protections may be available to the defendant. In short, criminal and private claims are generally dealt with separately under common law.

In the United States, for example, criminal law is a system in which cases are initiated at the behest of the state. The criminal law system is meant to regulate and punish behavior that is construed as an offense against the public, society, or the state. An example might be a murder case or, in the animal lawAny legislation, law, or legal challenge related to nonhuman animals, especially concerning their rights or welfare. realm, a felony charge for cockfighting. In such cases, the right to a jury trial is a requirement unless waived by the defendant. Typically, cases are brought by the state, and victims may not always have rights regarding their involvement. The applicable standard of proof for determining “guilt” is “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

In contrast, in the United States, civil law cases deal with behavior that constitutes an injury to an individual or other private party, such as a corporation. An example in the sanctuary world might be a dispute in which an organization sues a contractor for breach of contract, or if you have a dispute over an adoption. In such cases, matters are brought and dealt with by private parties in front of a court of law, not by the state. The standard of proof to prevail in a civil case is lower than that in a criminal case, and is generally “a preponderance of the evidence.”

How Do Criminal Cases Work In Code Law Systems?

In countries that operate under a code law system, criminal and private claims may be consolidated into one proceeding. For example, victims of a crime might be able to bring private claims within the context of a criminal prosecution.

There may be contexts in which animal organizations in common law jurisdictions become involved in criminal cases, such as if they work on cruelty, seizure, escapee or bust cases. To get more information on what your animal organization should consider before getting involved in such cases, you can check out our resource here! However, this resource is designed to introduce you to the legal process and remedies available to private parties dealing with conflict around an injury to an individual or an organization in civil litigation. To that end, next, we’ll look at the various gatekeeping mechanisms that courts employ to administer and resolve such conflicts.

Adversarial Systems Require “Actual Controversies”

One essential attribute that both common and code law systems share is that when it comes to resolving disputes, both function as adversarial systems – or setting up a contest between opposing parties. This contest is then moderated and decided by judges and juries who either directly represent the government or are appointed and vested with power by the government.

Generally, both systems require an “actual controversy” to trigger their courts’ jurisdiction (the official power to make legal decisions or judgments.) As a result, gatekeeping mechanisms built into legal systems restrict what kinds of conflicts can be heard there. As mentioned above, in a code law system, the kinds of disputes a court can hear are constrained by its written legal code. Similarly, in common law systems, there are also limits, although how those limits function looks a little different.

As an example, Article III of the Constitution in the United States limits federal courts’ jurisdiction or official power to make legal decisions or judgments. Over time the Constitution has been interpreted such that under this Article, courts are limited to reviewing “actual cases and controversies.” This means that:

- The parties must truly be adverse;

- The dispute must be concrete and not hypothetical;

- And the dispute must be something that can be resolved with the award of specific relief.

These requirements have been translated into multiple legal doctrines, including the questions of plaintiff “standing,” “mootness,” and “ripeness.” These gatekeeping mechanisms mean that for a court to have jurisdiction over a conflict, a plaintiff must demonstrate an “injury-in-fact” that is traceable to the defendant’s challenged action. The injury must also be one that the court can address with its decision.

The “case or controversy” requirement prevents courts from issuing what are known as “advisory opinions.” An example of a kind of case that would likely NOT be heard by the courts due to these doctrines would be a sanctuary suing the government for access to vaccines for highly pathogenic avian influenza (“HPAI.”) We address that specific question at some length in our resource on HPAI and the law so you can check out our detailed analysis there as an example, but it is one of many kinds of conflicts that may not amount to a “case or controversy” that can be addressed by courts of law in common law systems. On a related note, in addition to being limited in the kinds of cases they hear, courts of law are also limited in the kinds of remedies they can offer. We’ll look at that next.

The Kinds Of Remedies Available Under Judicial Systems

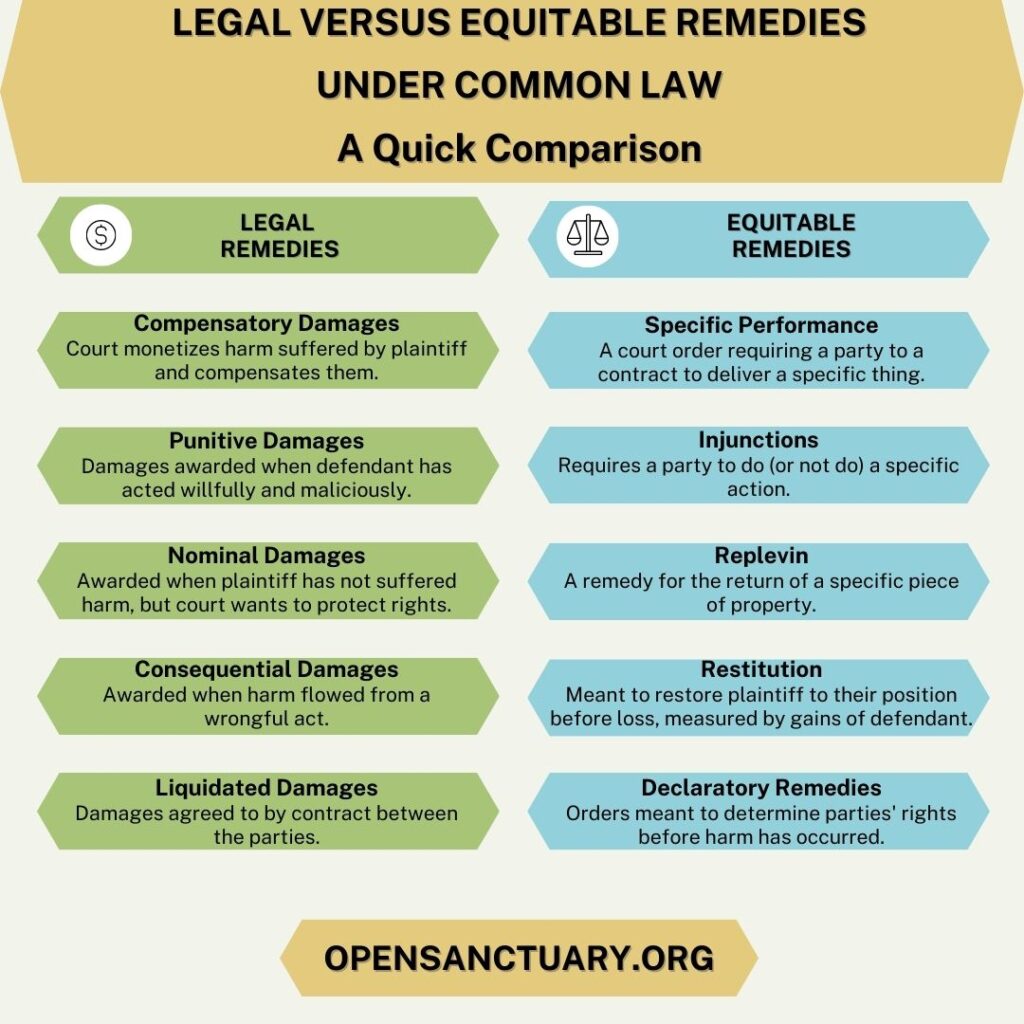

Remedies are how courts achieve “justice” in any matter involving legal rights. A court can order them after judgment, a settlement, or an agreement between the parties. As noted above, courts limit the matters they hear. The remedies that they offer are also limited.

In code law systems, remedies are meant to be “self-evident” based on the clear expression of rights and duties outlined in the legal code. In other words, for any given issue, the code is meant to offer strict guidance on what remedy a judge may offer after making their findings regarding the facts of the case. Any silence in the code is meant to be filled based on general legal principles, equity, and the spirit of the law.

In common law, remedies are much more complex because judges have much more discretion. They are divided into two general categories: legal and equitable remedies. The reason that the distinction between these two categories is important is because some jurisdictions have separate courts for plaintiffs seeking different kinds of remedies. For example, a plaintiff seeking monetary damages for a breach of contract might need to go to a “law division.” In contrast, a plaintiff seeking an order to regain ownership of an animal might need to go to an “equitable division.” Confusing? Let’s look at a few legal and equitable remedies under the common law below, which may help clear this up.

Legal Remedies Under Common Law

Legal remedies typically involve awarding monetary damages to compensate a plaintiff.These damages are intended to compensate the injured party for the harmThe infliction of mental, emotional, and/or physical pain, suffering, or loss. Harm can occur intentionally or unintentionally and directly or indirectly. Someone can intentionally cause direct harm (e.g., punitively cutting a sheep's skin while shearing them) or unintentionally cause direct harm (e.g., your hand slips while shearing a sheep, causing an accidental wound on their skin). Likewise, someone can intentionally cause indirect harm (e.g., selling socks made from a sanctuary resident's wool and encouraging folks who purchase them to buy more products made from the wool of farmed sheep) or unintentionally cause indirect harm (e.g., selling socks made from a sanctuary resident's wool, which inadvertently perpetuates the idea that it is ok to commodify sheep for their wool). that they have suffered. A court can award several types of damages in an action at law. We’ll take a look at each and offer some examples.

These Examples Really Are Hypothetical!

All hypothetical scenarios offered in this resource are indeed hypothetical: they are not based on any “real-life situation.” They are meant for educational purposes only.

- Compensatory damages are awarded when a court monetizes the harm suffered by a plaintiff and gives them a corresponding money judgment.

- Example: A sanctuary contracts to install a shed for animal food storage, but the shed is defective, and the contractor refuses to fix or replace it. If the sanctuary chose to go to court about this, the court might award the sanctuary the cost of repairing or replacing the shed.

- Punitive damages are awarded with the aim of punishing a defendant in a civil action (because, again, in civil suits under common law systems, criminal sanctions are unavailable to private parties.) In general, they are at the court’s discretion, are not fixed by law, and are awarded when a defendant has acted willfully and maliciously.

- Example: If the contractor responsible for building the food storage shed in our example above got mad at the sanctuary’s complaints and decided to burn down the shed, a court might decide to award the sanctuary punitive damages. Note that the contractor might also be subject to criminal charges at the discretion of the jurisdiction’s prosecutors!

- Nominal damages are awarded when a court has decided that a plaintiff has not suffered an actual harm but that their rights must be protected, or in cases where plaintiffs cannot prove the amount of their losses. In such cases, a small amount of damages (like a dollar) might be awarded to protect a plaintiff’s rights.

- Example: Let’s change our shed example again slightly. In this example, instead of fixing or replacing the shed, the contractor just removes it and refuses payment from the sanctuary. The sanctuary is able to find another contractor to build the same shed for the same price pretty quickly but still sues the original contractor for breach of their contract. In this case, the original contractor has still technically breached the contract, but the sanctuary might not be able to demonstrate that the breach damaged them, so a court might award nominal damages.

- Consequential (or special) damages might be awarded in a case where harm to the plaintiff has occurred, not as a direct consequence of a defendant’s action, but the harm flowed naturally from the wrongful act.

- Example: Let’s now imagine that the contractor has installed the defective food storage shed, but the sanctuary did not realize that the roof was defective until a severe rainstorm came, soaking and ruining all the food inside. In this case, a court might award the sanctuary the cost of the ruined food as consequential damages.

- Liquidated damages are damages that the parties have agreed to by contract in anticipation of a dispute when damages might be difficult to calculate. Liquidated damages provisions in contracts are not always enforced by courts, however.

- Example: Let’s change our shed example again and imagine that instead, a sanctuary has contracted to have a small barn and enclosed and roofed run area built in anticipation of the arrival of a new flock of rescued turkeysUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated turkey breeds, not wild turkeys, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource.. They build in a provision for liquidated damages of $1000 into the contract in the event that the shed is not constructed as agreed upon in time for the arrival of the turkeys. The contractor finishes the shed but doesn’t screen or roof the turkeyUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated turkey breeds, not wild turkeys, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource. run in time. The damages to the sanctuary in this case are very hard to measure. The turkeys technically have a home but don’t have enough space. The sanctuary has to figure out how to safely accommodate these birds while their screened and roofed run is completed. If they can’t come to terms with the contractor, the sanctuary might sue the contractor for the $1000 of liquidated damages as specified in the contract. However, a court may or may not decide to enforce this provision, depending on the jurisdiction and the context!

The Common Thread When It Comes To Legal Remedies Under Common Law

You can probably already guess it! It’s about monetizing harm. In virtually all cases where a plaintiff seeks a remedy at law, a court will consider dollars and cents. This can be particularly frustrating in a sanctuary context where we view animals as “more than” property. Unfortunately, the law has not evolved in parallel to our views. For example, consider a hypothetical case where a sanctuary sheep resident has been accidentally injured by a shearer, leading to an infected wound and substantial vet bills. If the shearer and the sanctuary cannot come to terms together, going to court may lead to some unexpected results. Even if the sanctuary’s veterinary bills amount to substantially more than the “market value” of the sheep, a court might restrict its award of damages to the sanctuary to that market value based on the fact that the sheep is technically property! While there is a gradual shift within the legal system when it comes to how courts view animals, it is slow and there is no guarantee that you can convince a court that an animal you are advocating for is worth more than their value as a commodity at market.

Equitable Remedies Under Common Law

Do equitable remedies under common law offer more leeway for “justice” outside of monetary damages? Equitable remedies are indeed designed to offer remedies in situations where money may not provide complete relief to injured plaintiffs. Sometimes, equitable remedies are known as “coercive remedies” because if the defendant willfully disobeys this kind of order, they might be jailed, fined, or otherwise punished for contempt.

However, equitable remedies also have limits. There is usually no right to a jury trial in a case tried in equity. Also, in some jurisdictions, if you are seeking equitable remedies, you might need to go to an entirely different court than if you are seeking legal remedies, although some courts will issue both. You also may need to prove that no legal remedies are available to resolve a breach of contract or other dispute before a court considers equitable relief!

We’ll look at a few forms of equitable relief: specific performance, injunctions, restitution, replevin, and declaratory judgment. Then we’ll give you some examples of how they work below!

- Specific performance is a court order in a contract case requiring a breaching defendant to deliver a unique thing (generally land, or a unique form of personal property) to the plaintiff.

- Example: Imagine that a sanctuary has entered into a contract to purchase a neighboring farmer’s land. This land adjoins their goat pasture, and has a perfect barn and pasture for accommodating some newly planned incoming goat residents! Now imagine that the neighbor gets a better offer from another person for the land after entering into the contract with the sanctuary and decides to breach their contract with the sanctuary. The sanctuary might be able to sue their neighbor for specific performance of their contract because the land is unique, and no other remedy would fully compensate them for the contract breach here.

- Injunctions are considered extraordinary remedies by courts. An injunction basically requires a defendant to do (or not to do) a specific action to avoid injustice and irreparable harm to the plaintiff. In deciding whether or not to issue an injunction, a court will balance the irreparability of harm and inadequacy of damages to the plaintiff against the harm caused to the defendant and potentially the public interest.

- Example: Let’s reimagine the above example with the sanctuary and its neighbor. Imagine instead that the neighbor who adjoins the property doesn’t really like the sanctuary and decides to keep a garbage pile on the boundary adjoining the sanctuary’s goat pasture. They also hold regular “garbage fires” where they burn garbage on the boundary. On a few occasions, those fires have gotten out of control and burned part of the sanctuary’s pasture, and the sanctuary is also concerned about the fumes from the garbage fires. They try to talk to their neighbor with no positive results. Law enforcement isn’t ready to assist them since “no real harm” has occurred. Ultimately the sanctuary is so concerned they decide to sue the neighbor and ask the court to issue an injunction against the neighbor holding further garbage fires that might cause damage to sanctuary property or harm residents. In deciding this case, the court will engage in a balancing act between the interests of the sanctuary and the interests of the neighbor. Depending on the judge, the jurisdiction, and the local culture, this could go either way.

- Replevin is a unique equitable remedy that may be of specific interest to animal sanctuaries and rescues. Replevin is an action taken by a plaintiff who wishes to recover a specific piece of property from a defendant. Again, while it’s distasteful to those of us working in sanctuary and rescue work, animals are considered “property.” Replevin may be a remedy to consider in cases where a sanctuary wishes to recover an animal that they “owned” from a context where the animal was placed, for example, in the context of an adoption or foster situation gone wrong.

- Example: After significant work vetting homes, a sanctuary has adopted out two roosters who are survivors of cockfighting to an individual, with the understanding that due to their background, the roosters should not come into contact with one another, but that the roosters also do deserve and require the company of their own species. Their adoption contract specifies that these roosters should not be forced to interact with each other or other roosters but that they will thrive well in individualized runs with one or two hen companions. The adoption contract also includes a clause for the sanctuary to reclaim the roosters if the birds’ needs are not being met. After placement, the sanctuary soon sees on social media that the adopted roosters have just been let loose together and are experiencing new trauma as a result. The sanctuary requests the return of the roosters, but the adopter refuses. This might be an example where the sanctuary might sue for the replevin of these birds. Rules and views on replevin vary wildly by jurisdiction, so it’s always best to have your adoption contract reviewed by qualified local counsel before starting an adoption program. Also, you should definitely talk to an attorney in detail should you find yourself in a situation where you might want to file a replevin action.

- Restitution is an equitable remedy similar to, but distinct from legal damages. Restitution is meant to restore a plaintiff to the position that they occupied before their rights were violated. It’s usually measured by a defendant’s gains from the violation, versus a plaintiff’s losses to prevent the defendant from being unjustly enriched by the wrong. The remedy of restitution can result in either a monetary recovery or the recovery of property.

- Example: Let’s revisit our shed example above. A sanctuary contracted with a builder to have a shed built, but the shed proved to be inappropriate and inadequate for the sanctuary’s needs. The sanctuary tries to negotiate with the builder, but the builder gets mad, removes the shed and sells it at double the price to another farmer. The sanctuary sues, and in court, the judge decides that the sanctuary is not just entitled to the cost of the shed they contracted for but also to the gains the builder realized in selling the shed.

- Declaratory remedies are sought when a plaintiff wishes to be made aware of what the law is, what it means, or whether or not it is constitutional so that they can take appropriate action. Courts are generally hesitant to issue declaratory judgments, especially since they are often sought before the party in question has suffered an injury. The primary purpose of this kind of remedy is to determine an individual’s rights in a particular situation. Sometimes, however, this remedy may be available.

- Example: A sanctuary adjoins a neighbor who has laid out boundaries for new fencing that encroaches on the sanctuary’s property lines. The sanctuary is alarmed! After reviewing their land survey and discussing the matter with their neighbor, they find the neighbor unwilling to bend with regard to the fencing boundary. The sanctuary sues the neighbor asking for a temporary injunction, and for a declaratory judgment from the court that requires the neighbor to refrain from placing fencing on the lines planned, and to make a final determination on where the property boundary lies.

A Note On Provisional Remedies

Another form of equitable relief is known as a provisional remedy. This is a temporary form of relief that plaintiffs can seek to prevent further harm to themselves while the court is still determining their rights. Such remedies include temporary injunctions, attachment, and garnishment.

The Costs And Benefits Of Litigation

It’s fair to say that no one wants conflict to escalate to a point where they need to seek outside intervention (such as from courts of law) to resolve it. If you do encounter a conflict that you are considering escalating to this level, it is well worth considering the various costs and benefits that can accompany it.

The Benefits Of Legal Conflict Resolution

There are some advantages to using the legal system to resolve a conflict that you have been unable to resolve otherwise. By its nature, the legal system serves to “box” a conflict into a manageable package by restricting the kinds of cases courts will hear (as explained above) and by strictly defining the issues in question in disputes that are heard. In this sense, it can offer some efficiency. Consider our example of a sanctuary with an ongoing neighbor dispute over land boundaries again. Neighbor disputes can often get bitter and emotional, and these feelings can often get conflated with what might be an otherwise simply defined conflict. A court will identify the main legal issues quickly and address those alone and conclusively. Court rules, such as codes of civil procedure and rules of evidence will prevent other issues that do not bear on the conflict from “creeping into” the conflict.

This can often prevent conflicts from being drawn out and complicated by issues that may be aggravating and stressful, but not directly relevant to the specific issues at stake in the case. So the court will consider matters like land surveys and recorded land records but won’t indulge neighbors shooting insults or accusations back and forth that are unrelated to the boundary dispute. For example if, during the course of their sparring, the sanctuary’s neighbor set up a sprinkler to douse animal blankets that the sanctuary was line drying, this kind of argument will not be given much leeway or space in a courtroom context.

Another benefit to using courts of law is that a court decision will offer a clear and tangible resolution to a conflict that is enforceable by authorities. In our example of the sanctuary’s boundary dispute with their neighbor, after hearing the case and considering the evidence, the court will offer a decision that clearly articulates the boundary of the land and which will delineate the rights and responsibilities of the parties to the dispute going forward, such as for example, if a fence line must be moved. If the court’s decision is not respected or complied with, the aggrieved party can return to court to seek enforcement measures or even sanctions to get the matter resolved finally. In this way, the parties to a case will get closure even if the result may not be entirely satisfactory to one or both of them.

The Costs Of Legal Conflict Resolution

Let’s talk money. Litigation is costly. In general, if you plan on going to court, you would be well advised to hire a skilled attorney in your jurisdiction who is knowledgeable regarding the subject matter of your conflict. This can come with high costs. Attorneys may charge you a retainer, or bill you on a contingency, a flat fee, or an hourly basis. Or you might luck out and find an attorney willing to represent you on a pro bono or a no-charge basis (but they may still charge you for their costs!) Let’s take a second to define each of these billing systems.

Always Put Your Agreements With Lawyers In Writing!

Whether you are lucky enough to get pro bono (without charge) representation, or you come to another fee agreement with your attorney, make sure you get your understanding in writing so that you know what expenses (such as filing, travel, or other fees) you might have to pay, as well as a full understanding of how your lawyer will bill you!

A retainer fee is one that is paid by a client to a lawyer in order to secure their services. It is essentially like a deposit, which “reserves” a certain amount of the lawyer’s time at an agreed upon rate, which may be either a flat fee for set services or an hourly rate (both of these are discussed further below.) Retainer fees are typically deposited in a lawyer’s client trust account, and used for early case expenses and billing. Again, a retainer agreement should always be made in writing.

A contingency fee means that payment to the attorney is contingent upon the case’s successful outcome. This billing system is used when the plaintiff is seeking monetary damages. It can give a plaintiff without funds access to an attorney willing to work for them, solely based on the prospect of succeeding in the case. If the attorney successfully recovers damages for the plaintiff, they will take an agreed-upon percentage of the recovery as their fee. If the attorney is not successful, the attorney is not paid. However, sometimes you are still responsible for filing or other fees! And sometimes, after the contingency fee and expenses are paid, you may not have much of a recovery! Also, the legality of contingency fees is often subject to restrictions, which will depend on your jurisdiction. Finally, keep in mind that this kind of fee arrangement is only possible where there is a possible monetary recovery. If you are suing for equitable relief, you will have a harder time finding an attorney willing to undertake such a matter on a contingency fee basis.

With a flat fee, an attorney will charge you a set amount for a task or a group of tasks. Again, it’s imperative to set your agreement out in advance and in writing so that expectations are clear on both sides. With this kind of arrangement, the benefit is that you will generally have a clear expectation of what your legal services will cost – but there may be unexpected situations that arise which require you to revisit your arrangement with your attorney.

If you don’t have a contingency or flat fee arrangement with your attorney, they will likely bill you hourly. They should provide you with their billing rate (as well as the rates of any associates or assistants they employ on your matter), how they bill you, and the payment terms. It’s not atypical for lawyers to bill by the tenth of an hour, which means that your six-minute phone call “just to check in” might end up being added to your bill! You may also be billed differently depending on whether your lawyer is working on your matter in their office, is in transit, or in court. Further, lawyers’ hourly rates will depend on where they are located, their experience, the difficulty of the matter in question, the expertise that may be required, and more. Again, please make sure you get a written explanation of your lawyer’s rates. If you have a cap on the fees you want to spend, make that clear to your lawyer in writing.

Now that we’ve discussed financial costs, let’s talk about the investment of time and energy in litigation. Leading up to trials, there is generally a process known as “discovery,” which is the formal process through which parties to the litigation share the information, witnesses, and other evidence they will present at trial. Often this involves depositions, or out-of-court sworn statements given by any person (party or witness) who may be involved in a case. Giving a deposition can be akin to giving testimony in court, and it can be stressful and demanding, especially since both sides have the right to be present. Further, producing records requested by the other side can also be exhausting and stressful. For example, you and other parties involved may be required to respond to subpoena requests, requiring you to submit records and other documents or physical evidence for inspection. This might even include people like your veterinarian, if the matter involves the care or health of an animal!

All this can demand a significant amount of energy expenditure on your part and on the part of folks called to participate in the process. On top of this, the legal process can take a great deal of time. Depending on your jurisdiction and the caseload that your local courts carry, from the time your complaint is filed to the time it is resolved, many years can pass! Even if you prevail at trial, resolution can take even longer if the other side decides to appeal.

Finally, another cost of litigation is that it will not address any underlying systemic issues that caused your conflict to arise. Because courts are designed to “box conflicts” into packages that can be addressed by the remedies available under law and equity, decisions made by courts may only address part of a conflict.

Let’s revisit our sanctuary, which is having a boundary dispute with its neighbor. Imagine that the entire conflict arose from a basic misunderstanding. When the sanctuary moved in, the neighbors were initially excited, thinking that they could potentially get eggs and fiber from the sanctuary residents. When the neighbors approached sanctuary staff to learn more about them, and ask them about this, the staff happened to be in the midst of a hectic day. They didn’t realize that these were their new neighbors and addressed them tersely, saying, “We don’t contribute to animal abuse, and we would never consider exploiting our residents this way.” The neighbors were taken aback and hurt, and the conflict escalated from there.

From the perspective of a sanctuary dedicated to providing forever compassionate and non-exploitative homes to animals, what the staff said was not inherently wrong. However, there may have been a better way of communicating this message. The de-escalation of everyday interactions can go a long way to avoiding larger-scale conflicts. However, a court will not generally help with such matters. And ultimately, even though the court may resolve the legal dispute around the land boundary, hard feelings between the sanctuary and their neighbor may remain, and in fact be inflamed as a function of the legal action. This may in fact lead to other conflicts in the future.

Want To Learn More About Communication Practices To De-Escalate Conflict And Build Transformative Relationships?

As mentioned above, using the legal system is not the only way to address conflicts. In the example of the sanctuary involved with a neighbor dispute that was born of a misunderstanding, perhaps their conflict could have been mitigated by using thoughtful communication and fostering a culture of mutual accountability. To learn more about how you can practice this kind of communication, check out Part 2 of our series on transformative justice and community accountability!

Alternative Dispute Resolution

What is alternative dispute resolution? In its broadest definition, it is any means of resolving a dispute between two parties outside of a courtroom. Mediation and arbitration are the most common forms of alternative dispute resolution, or “ADR,” that still operate under similar parameters as courts of law.

In the judicial system, ADR has become increasingly more employed as a method of avoiding litigation expenses and helping parties come to terms before they go to court. Especially in jurisdictions with a high volume of cases, if you file a lawsuit, you may be required by the court to undergo mediation before undergoing litigation in the court. This is done to economically and efficiently resolve disputes before using the resources of the judicial system.

You can also draft contracts that include provisions that, in the event of a dispute, require that the parties resolve the dispute using ADR instead of the courts. To learn more about how to do that, you can check out our resource on independent contractor agreements, which has a section explaining how that works here. The two most common options are for parties to agree to share the cost of the neutral third party mediating or arbitrating their dispute, or for the loser to bear the cost.

You can even create a bifurcated process that starts with mediation, and if the dispute is not resolved in this way, it is escalated to arbitration. While this may sound prolonged, using ADR can save a lot of expense when it comes to avoiding court filing fees, hiring lawyers, going through the discovery process and then proceeding to litigation. It is a worthwhile option to consider with respect to any legal disputes a sanctuary may face. It is also worth consulting with your own counsel to find the right option or mix of ADR options that best fit your sanctuary’s needs. So let’s now quickly consider the differences between the two processes.

Mediation

Typically, mediation is nonbinding and is a way to get two parties together so that they can sit down and talk through their misunderstandings with the help of a neutral third party. Again, in some jurisdictions, you may be mandated to go through mediation before attempting to litigate your issues before a court. Your mediator will be appointed, will hear the issues, and will try and help the parties come to some kind of shared understanding on how to resolve them. The rules of civil procedure and evidence will be highly relaxed if they apply at all. Sometimes, in this less formal setting, conflicts can be more easily resolved. However, should a mediated agreement between parties ultimately fall apart, there is no mechanism for enforcing it. The parties will then need to either seek a binding decision through arbitration or litigation in court.

Arbitration

Arbitration is more formal than mediation and is generally binding. While you may not need to fully observe the formal rules of procedure and evidence used in a court proceeding, there will be more strict guidance regarding what evidence is admissible and how it may be introduced in the proceeding. A single arbitrator or a team of arbitrators may conduct arbitration. There is a formal organization of arbitrators that parties to a dispute may contact to hire to arbitrate their disputes. Unlike a decision made by a mediator, a decision by an arbitrator can be brought to a court in the relevant jurisdiction to have it enforced.

Alternatives To Addressing Conflicts Outside Of The Legal System

As mentioned above, there are alternatives outside of the judicial system when it comes to conflict support, conflict de-escalation, and building accountable communities. As you probably noted, the judicial system generally focuses on assigning liability or guilt to parties within an adversarial context. However, this isn’t the only way to manage disputes. From our resource on Conflict Support For Your Animal Organization Part 1: Understanding Dominant Culture, How It Shapes Our Behavior And Envisioning Alternatives, we’ll briefly summarize two other options: restorative and transformative justice.

Restorative justice acknowledges the impact of a conflict on both the individuals involved, as well as on the community. It seeks to hold the person(s) responsible for the harm accountable and provides a form of reparation. It allows for complexity and is less likely to lead to the removal of individuals from their communities. However, one shortcoming of restorative justice is that it often relies on existing institutions and processes that fall short of creating alternatives and critiquing systems of oppression by solely holding individuals responsible for situations. For example, some courts are now incorporating restorative justice practices into managing their caseload as an alternative to mediation or arbitration, resulting in some of the punitive nature of court-administered justice filtering into this system.

In contrast, transformative justice is a framework grounded in the belief that people occupy multiple roles and can be both harmed and harm others. It seeks to ensure the safety and healing of everyone involved and adapts the process to the specific situation. It encourages the imagination of alternatives beyond the current system to address issues of power and privilege. This approach may seem idealistic, so implementing it on a large scale can pose a significant challenge. Its power lies in relationships rather than third-party objectivity. However, in smaller-scale communities, such as farmed animal sanctuariesAnimal sanctuaries that primarily care for rescued animals that were farmed by humans. and rescues, where we seek to model an alternative way of existence that rejects the assumptions and hierarchies of the dominant culture, transformative justice may be an attainable and workable ideal!

Conclusion

When it comes to conflict, ending up litigating in a court of law is not always an ideal option, and due to the expense and stress associated with it, it should probably be a measure of last resort. Your organization will be well served by investing in legal counsel who can help you navigate potentially conflict-riddled interactions such as contracts, property disputes, or adoption disputes in advance, by drafting tailored contracts for your sanctuary that anticipate and provide for contingencies. Exploring new communication practices and ways to help build community accountability can also help avoid internal organizational conflict that might otherwise escalate in undesirable ways. If you do find yourself in a position where you must use the court system to resolve a conflict, having a basic understanding of your jurisdiction’s legal system is invaluable, as is hiring a skilled attorney to help you navigate it.

Action Steps

- Before you ever encounter a conflict that may rise to the level of litigation, seek out and develop a relationship with an attorney who can help you manage liability and navigate conflict should it prove necessary.

- To avoid disputes, keeping agreements with other parties in writing is always an excellent safeguard to avoid miscommunications and misunderstandings. This includes your agreements with your lawyer!

- Consider implementing practices within your organization to de-escalate inter-organizational conflict and train your team to do the same when they encounter strife with outside parties.

- If you need a neutral third party to resolve a conflict that cannot be de-escalated by other means, consider mediation or arbitration before litigation to cut down on the expenditure of your organization’s funds, time and energy.

SOURCES

A Forever Home? Adoption Program Considerations For Animal Sanctuaries | The Open Sanctuary Project

Breaking Down An Independent Contractor Agreement | The Open Sanctuary Project

What Is A Land Survey And How Can It Help Your Animal Organization? | The Open Sanctuary Project

Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza: Your Sanctuary And The Law | The Open Sanctuary Project

About Restorative Justice | University Of Wisconsin-Madison Law School

Transformative Justice: A Brief Description | Transform Harm: A Resource Harm For Ending Violence

The Common Law And Civil Law Traditions | Berkeley Law

Constitution Annotated: Analysis And Interpretation Of The U.S. Constitution | Congress.Gov

What Is The Civil Law? | LSU Law

Nature Of Remedies | Law Library – American Law And Legal Information

Law For Entrepreneurs: Remedies | GitHub

Compensatory Damages | Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School

Punitive Damages | Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School

Nominal Damages | Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School

Consequential Damages | Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School

Liquidated Damages | Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School

Specific Performance | Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School

Injunctions | Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School

Replevin | Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School

Restitution | Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School

Declaratory Judgment | Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School

Alternative Dispute Resolution | Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School