We Have A Podcast Episode On This Subject!

Want to learn about this topic in a different format? Check out our episode of The Open Sanctuary Podcast, all about avian predator-proofing tips!

Resource Goals

- To learn about the kinds of risks that predators present to your avian residents;

- To learn about some specific predator types;

- To learn tips on how to familiarize yourself with predator types in your environment and site avian living spaces appropriately;

- To learn about the importance of and how to build impenetrable overnight living spaces;

- To learn about infrastructure that will secure the perimeter of your avian residents’ daytime spaces from digging, climbing, and aerial predation risks;

- And to learn about protocols caregivers can use to maintain infrastructure and ensure ongoing predator-proof living spaces for your avian residents.

Introduction

Protecting sanctuary residents from predators is essential regardless of the species for whom you care, but many farmed bird species are particularly vulnerable to predation and require more protective living spaces than other residents, such as large mammals. In this resource, we’ll consider the types of risks chickens, turkeysUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated turkey breeds, not wild turkeys, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource., ducksUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated duck breeds, not wild ducks, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource., geeseUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated goose breeds, not wild geese, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource., chukars, quail, guinea fowl, peafowl, and similarly sized sanctuary bird residents face and how you can provide them with living spaces that keep them safe. While emus and ostriches do need protection from larger predators, given their size, mature emus and ostriches do not face the same degree of risk of predation as smaller avian species, so they are not the focus of this resource. Similarly, because parrots are primarily kept indoors and have very different needs in terms of housing, they will be addressed in a future resource.

In this resource, we’ll focus on the types of infrastructure necessary to keep predators out of avian living spaces. However, protecting residents from predators goes beyond living spaceThe indoor or outdoor area where an animal resident lives, eats, and rests. design – it’s also vital to enact practices that help reduce the chances of conflicts with wildlife in the first place (and to avoid practices that attract wildlife toward resident areas, thereby making conflicts more likely). You can read more about this topic here.

Residents Need Protection Against More Than Just Predators!

While proper predator protection is paramount, folks caring for avian residents must also consider the risk of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI). HPAI is a serious health threat to birds and poses a threat regarding legal control measures. We strongly urge sanctuaries caring for avian residents to stay informed about HPAI risks both in their region and more broadly so that they can enact appropriate measures to keep their residents protected. Depending on the current situation, providing outside access to your avian residents may not be safe, or you may need to provide them with a modified outdoor space. The following information is focused solely on predator protection. Additional measures are necessary to reduce the risk of HPAI. You can read more about this here.

Consider The Risks

First, it’s important to consider the predators in your area. Depending on where you live and your experience level, your first thought might be that predation is not a concern in your area. We cannot stress this enough – just because you have not seen or heard about predators in your area does not mean they are not there. If you care for farmed bird species, you absolutely must work under the assumption that there are predators in your area. This is true even if your residents spend the majority of their time in your home and only go outside while supervised. We recommend researching the types of predators that live in your region and accepting that they pose a risk to your residents regardless of whether you have ever seen them near your sanctuary or not.

While far from an exhaustive list, the following species pose a predation risk in the U.S. and areas of Canada and Mexico, though the degree of risk posed may vary depending on your residents’ species/size/health (i.e., a button quail is going to be more vulnerable to certain predators than a turkeyUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated turkey breeds, not wild turkeys, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource., goslingsYoung geese are more vulnerable than mature geese, and a sick, injured, disabled, or broodyTerm used to describe a hen demonstrating behavioral tendencies associated with sitting on, incubating, and protecting a clutch of eggs, but a hen can be broody even if her eggs are removed. bird may be more vulnerable than other avian residents):

- Hawks – (particularly Harris hawks, Red-tailed hawks, Red-shouldered hawks, and Cooper’s hawks) – aerial predators who hunt during the day.

- Eagles – (including the Bald eagle and Golden eagle) – aerial predators who hunt during the day.

- Great Horned Owls – aerial predators who hunt mostly at night.

- Black vultures – aerial predators who search for food during the day.

- Foxes – (particularly the red fox) – can dig/squeeze under, climb over, or jump over fences to enter avian living spaces. Foxes are primarily nocturnal, hunting from dusk to dawn but sometimes hunt during the day.

- Coyotes – can dig under and climb/jump fences. They may hunt during the day or at night.

- Wolves – can dig under and climb/jump over fences. They typically hunt from dusk to dawn.

- Bears – can tear through many types of fencing and can also force their way into a coop if that is their goal. They may be seen at any time, day or night. Bears may initially be attracted to your residents’ food, which is one of the many reasons why all food should be put away overnight, and all spilled food should be cleaned. In areas where bears are common, it may be unsafe to store your residents’ food in or near resident living spaces.

- Wild cat species – (including bobcats and mountain lions) – can jump and climb over fences. They typically hunt from dusk to dawn.

- Raccoons – can climb over fences, open simple latches, and reach their arms through small openings to grab birds. They mostly hunt at night.

- Members of the weasel family – (including mink, fishers, badgers, and the common weasel) – depending on the species, they may enter avian living spaces by digging under fences or through flooring, by climbing, or by squeezing through very small openings in fencing or structures. Members of the weasel family may be active day or night.

- Opossums – may climb over fencing. They are typically active at night and may be more interested in eating eggs than killing birds, but they could pose a risk to smaller individuals.

- Skunks – depending on the species, skunks may be able to climb or dig under fencing. They are active at night and may be more interested in eating eggs than killing birds, but they could pose a risk to smaller individuals.

- Some snake species – (such as rat snakes) – can squeeze through gaps in fencing or structures. They may be active during the day or at night. They may be more interested in eating eggs than killing birds but could pose a risk to smaller individuals.

- Rats – can chew into/through wood and may live in your resident’s indoor spaces without you realizing it. They pose the greatest risk to birds overnight. Despite their small size, they pose a significant risk to both large and small birds.

- Snapping turtles – may attack birds near the edge of a pond or may attack waterfowl while they are on the water. They are primarily nocturnal.

- DomesticatedAdapted over time (as by selective breeding) from a wild or natural state to life in close association with and to the benefit of humans dogs – this includes your own companion dogs, as well as neighboring dogs and stray or feral dogs in the area. They may jump, climb, or dig under fences. Dogs may be active during the day or at night.

- Domesticated cats – this includes your own companion cats, as well as neighboring cats and stray or feral cats in the area. While cats may be too small to kill larger bird residents, smaller species and chicks are more vulnerable. Cats may climb or jump over fences or squeeze through gaps. They may be active during the day or at night.

Consider Human Threats As Well

In addition to non-human predators, it’s important to consider the risks other humans can pose. It is always critical to check the zoning regulations in your area to make sure that your resident population and operations conform to legal requirements. However, sometimes neighbors can be disgruntled or angered by bird calls, particularly in the case of more vocal residents such as roosters, peafowl, or guinea fowl, even if they are legal! It is not unheard of for frustrated humans to “take matters into their own hands” and take action that can harmThe infliction of mental, emotional, and/or physical pain, suffering, or loss. Harm can occur intentionally or unintentionally and directly or indirectly. Someone can intentionally cause direct harm (e.g., punitively cutting a sheep's skin while shearing them) or unintentionally cause direct harm (e.g., your hand slips while shearing a sheep, causing an accidental wound on their skin). Likewise, someone can intentionally cause indirect harm (e.g., selling socks made from a sanctuary resident's wool and encouraging folks who purchase them to buy more products made from the wool of farmed sheep) or unintentionally cause indirect harm (e.g., selling socks made from a sanctuary resident's wool, which inadvertently perpetuates the idea that it is ok to commodify sheep for their wool). your residents, including breaking into coops or even leaving poison in the area. If you face this kind of challenge, it is critically important that your residents’ enclosures be secured against human encroachments as well! This may involve padlocking secured runs and areas, using cameras and posting signage about your camera use on your property, and taking precautions to ensure nothing can be put into your avian resident living spaces by ill-intentioned humans!

As you can see from the examples above, different types of predators pose different types of risks and, therefore, require different preventative measures. Next, we’ll look at how living spaces can be designed to help protect your residents from predation.

Where To Set Up Avian Living Spaces

As we mentioned above, creating predator-proof living spaces is just one piece of the puzzle, albeit a very important one. Along the same lines of enacting compassionate practices and creating protective infrastructure (which we’ll address more below) that reduce the likelihood of conflict with wildlife, also consider the most appropriate location for avian living spaces in the context of predator protection.

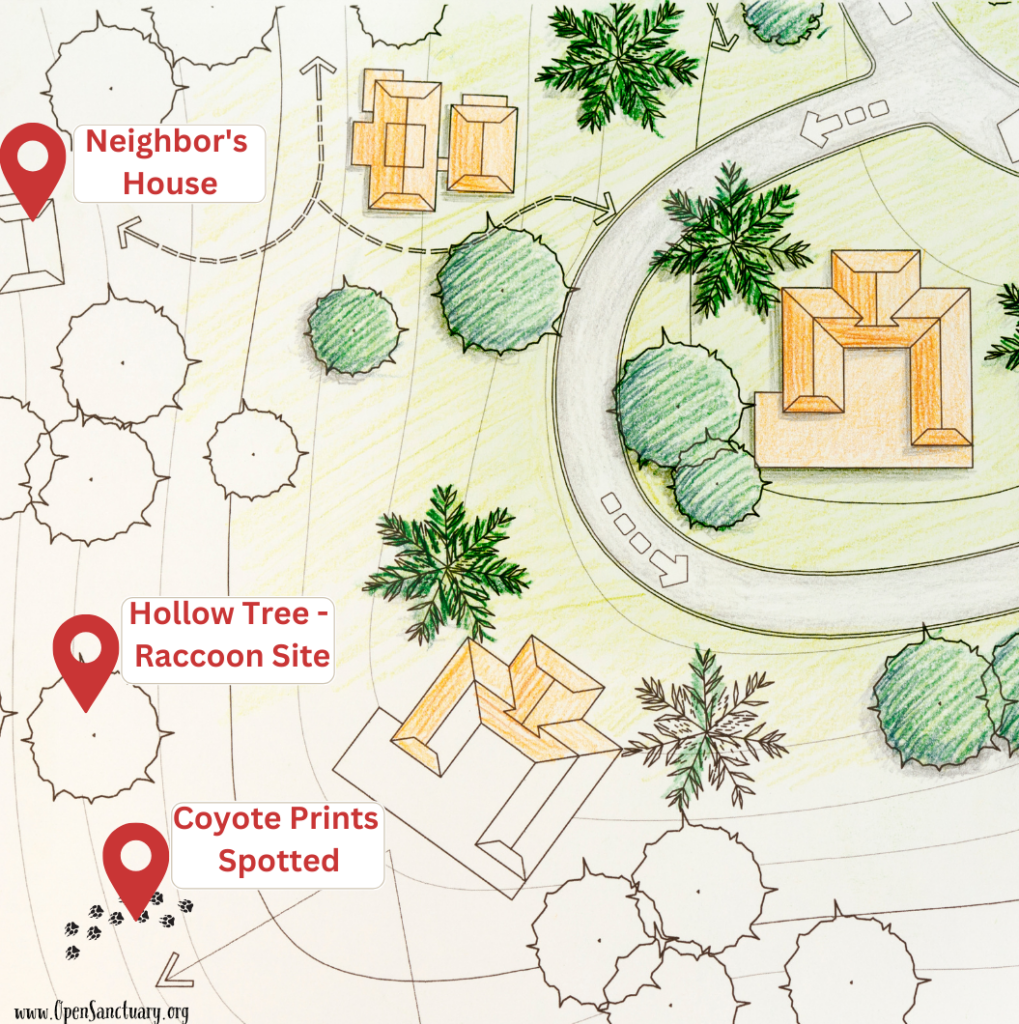

Take time to learn who lives on and around sanctuary grounds and how they use the space. This can involve taking measures like installing motion-activated cameras to get a good look at some of the other animals who may share your space. Another way to learn more about your wild-living neighbors is to pay attention to their tracks and scat. These are important ways to identify areas where wildlife frequent and can help inform your decisions about where to site avian living spaces. For example, you might notice raccoon tracks and scat around a hollow tree, an indicator that this may be a frequent sleeping area or favorite spot. This would definitely be an area to avoid in terms of siting an avian living space!

Being aware of and attuned to your wildlife population can help inform your decisions and allow you to avoid setting up avian living spaces in an area where conflict with wildlife is more likely. Additionally, setting up avian living spaces in areas closer to human dwellings or areas with more human presence (versus far away from these things) may reduce the likelihood of conflict with wildlife (at least during the day). Being thoughtful about where bird residents live and ensuring those spaces offer robust predator-proofing will help protect residents better.

Keep in mind, as well, that once predators have discovered an appealing area where they might be able to prey upon residents, they will generally be persistent! So it’s essential to try and site living spaces in a way that will avoid the conflicts in the first place versus finding yourself in a situation where you may have to relocate living spaces for your residents.

Start With Impenetrable Overnight Accommodations

While diurnal predators certainly pose a threat to avian residents, the period from dusk to dawn poses a particularly significant risk. Some predators are primarily nocturnal, but other species may adapt their behavior to avoid humans, coming out during the nighttime hours, which are often devoid of human presence. Additionally, farmed bird species do not see well in the dark, making them much more vulnerable to predators. For these reasons, avian residents should be closed into a fully predator-proof indoor space before dusk, and they should not be let out until it is light out. Despite not being fully dark, dusk and dawn pose significant risk of predation, so it is imperative that residents are fully protected during these periods as well as overnight.

So what does a fully predator-proof space entail? It should be a fully enclosed, solid structure that protects against a variety of threats. This includes:

Protection From Below

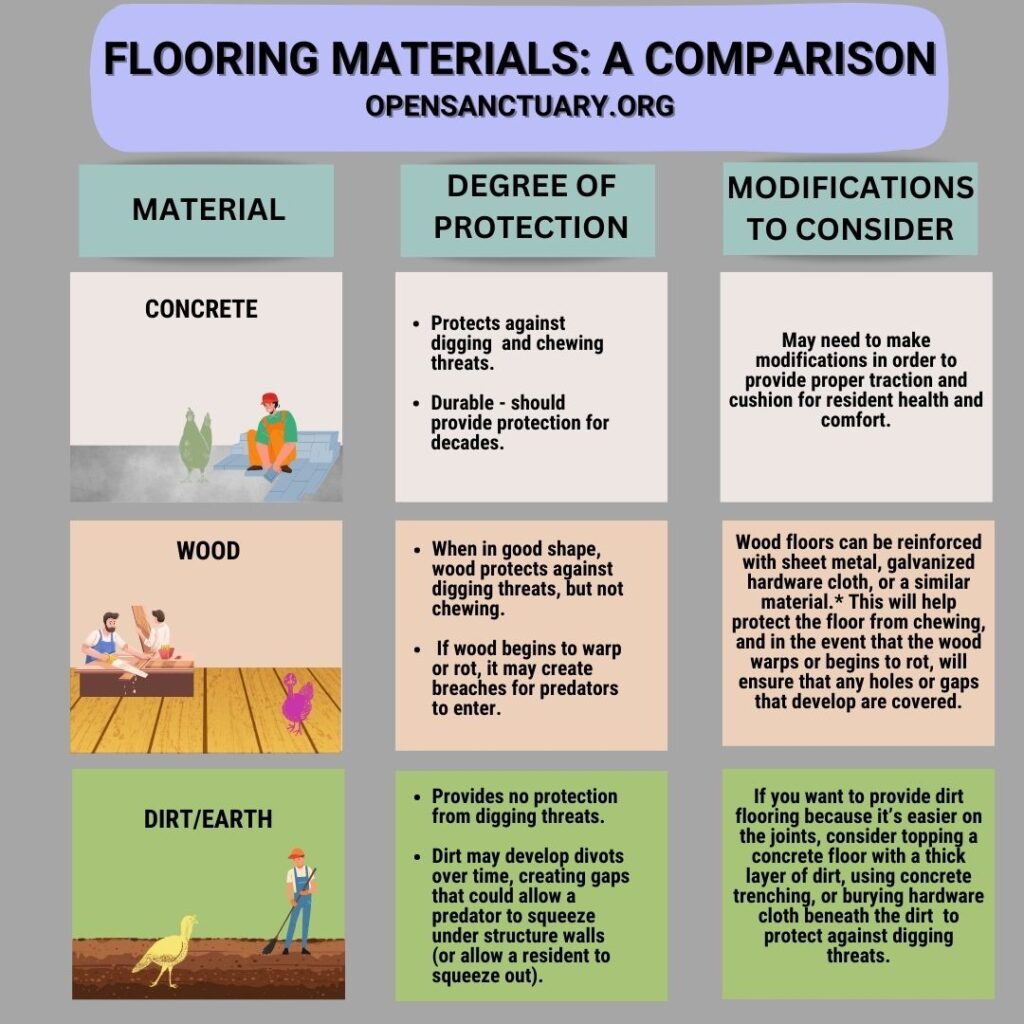

Robust overnight predator-proofing begins with an impenetrable base. When determining the most appropriate flooring options for your residents, you will want to consider what they need both in terms of predator-proofing and in terms of foot and leg health. Depending on the flooring option you use, you may need to make alterations in order to make it work from both a predator-proofing and resident health perspective. For example, while a concrete floor will offer the most protection against chewing and digging threats, concrete may be too hard for some residents and may need to be covered with thick, textured rubber mats. We recommend checking out our “Creating A Good Home” series for more specific tips about flooring for different species.

Here, we want to stress the importance of flooring options that will reliably keep predators out both now and in the future. Some flooring options, like an earthen floor, provide no protection from digging predators, and others, such as wood, may deteriorate over time, making them more susceptible to breaches. Rather than waiting for a breach to develop, we recommend being proactive and making modifications, as described below. While not the only flooring options available, below we’ll look at three common flooring materials to give you an idea of the degree of predator protection they provide on their own and modifications that can make your residents safer.

Be Conscious Of The Threat Of Foreign Body Ingestion!

When cutting galvanized hardware cloth/wire, do so in an area away from your avian residents, and take care not to drop any screws, nails, staples, etc. in resident spaces. Accidentally leaving pieces of galvanized wire or small metal objects in your avian residents’ living space can not only result in external or internal injury but if ingested can also result in heavy metal toxicity. To learn more about foreign body ingestion, you can check out this resource!

If you are considering a flooring/foundation option not covered above, be sure to assess if it can be dug or chewed into, as this will put residents at risk, and identify ways to enhance the protection provided. Also, be sure to consider how the material(s) will degrade over time and/or with exposure to moisture.

Digging And Chewing Threats

While some predators may dig or chew their way into your residents’ living space, keep in mind that other animals who do not pose a predation risk may also dig or chew into the space. While these animals may not pose a direct risk to your residents, the breaches they create may give predators easy access to your residents’ living spaces. Therefore, even if you feel certain that there are no predators in your area who will chew into the living space, it is still important to protect against chewing to ensure the space remains tightly sealed.

Protection From Above

Residents should be in a fully enclosed structure overnight, which means they should have a solid roof. Because of this, you may think that protection from above is a given; however, not just any roof will do. Just as an impenetrable base is vital to safe overnight accommodations, so too is a strong roof. In addition to offering residents protection from the elements, a strong roof will help keep them safe from predation. Some predators may jump onto the roof or otherwise test the strength of the roof while trying to find a way in, and a flimsy roof may become damaged or even collapse under the weight of certain predators. A flimsy roof may also be easily damaged by something completely unrelated to a predator (such as a fallen branch or heavy snow), putting residents at risk of both predation and injury. As with flooring, some materials may deteriorate over time, creating a breach for predators to enter through or for residents to exit the structure.

Keeping your residents’ living spaces properly ventilated is important for their health and comfort, but ventilation must be provided with predator-proofing in mind. Because members of the weasel family can squeeze through very small spaces and could easily wipe out an entire flock of residents overnight, any vents in the roof peak or soffits should be covered with ¼ inch galvanized hardware cloth to prevent predators from entering while still allowing for airflow.

Protection All-Around

Just as you need an impenetrable roof and foundation, all other aspects of the structure should keep predators out. Walls must be solid and sturdy. As with wood flooring, we recommend reinforcing wooden walls with galvanized hardware cloth, sheet metal, or similarly impervious material. Corners and area junctions between the walls and the floor or roof must be strong and free from gaps. Because wood may warp over time, reinforcing these junctions is wise. As a general rule, openings as small as a U.S. quarter (which, for our friends outside of the U.S., has slightly less than a 1-inch/2.54-centimeter diameter) should be covered or otherwise addressed to help ensure robust overnight protection. This will help protect against raccoons (who can reach their arm through tiny gaps to grab residents) and members of the weasel family (who can squeeze through small spaces).

If windows are left open overnight, they must be covered with galvanized hardware cloth. A simple screen is easily torn and will not keep residents safe. Similarly, chicken wire is insufficient protection. (More on this below!) Ensure galvanized hardware cloth is properly secured with screws to prevent it from being pulled off (which may happen with staples). If the structure has an exhaust fan, make sure it has no openings that would allow a predator to enter the space when the fan is not in use. We recommend using an industrial exhaust fan with locking shutters – these shutters will help seal cold air out when the fan is not in use and help keep predators out.

Make sure that all doors close tightly. Gaps under or around the door could allow certain predators to enter the space. Raccoons have been known to open simple latches, so you should employ additional methods of protection such as bungee cords, carabiners that screw closed, padlocks, or a double bolt snap if raccoons or similar predators live in your region.

Rats

While the goal of an impenetrable overnight space is to keep predators out, it’s important to consider that some predators, particularly rats, may inconspicuously take up residence in the space. They may live in the walls, between the roof and insulation, behind nest boxes, or under perch bales, for example. This will put your residents at risk regardless of the protection the space provides from outside threats. Because insulated walls can easily become rat habitats, insulation should be installed thoughtfully to prevent rats and other wildlife from gaining access to insulation (similarly, residents should not be able to access insulation). One way to do this is to sandwich foam board insulation between layers of galvanized hardware cloth (or a similarly impervious material) to keep rodents from chewing or accessing it. In a structure with wooden walls, this means each wall might consist of the following: the interior wooden wall, galvanized hardware cloth, foam board insulation, another layer of galvanized hardware cloth, and then the exterior wooden wall. Never simply place exposed insulation against the walls or roof. Especially in colder temperatures, rodents will create a cozy home inside your insulated walls if they can! Rats can cause severe and even fatal injury to avian residents, particularly in the dark when residents cannot see. Therefore, you must take compassionate steps to both discourage rats from living in the space and also to regularly check the space for signs rats may be making themselves at home. If you haven’t already checked out Compassionate Wildlife Practices At Your Animal Sanctuary, we strongly encourage you to do so!

Establish A Bedtime Routine

Whether you are solely responsible for securing residents in their overnight space or have a team of staff or volunteers who share this responsibility, establish an evening routine focusing on predator protection. For starters, be sure to have all your avian residents safely closed in before dusk! Make sure anyone responsible for closing in residents is aware of how many residents live in the space so that they can ensure everyone has been accounted for (and if someone is missing, have a plan in place to search for them). While automatic coop door closers do exist, we do not recommend their use. A resident who is late to come to bed, injured, sick, or broody in an outdoor nest could be locked out of their space without anyone knowing, leaving them at mortal risk. Additionally, all of your residents will be at risk if the door malfunctions.

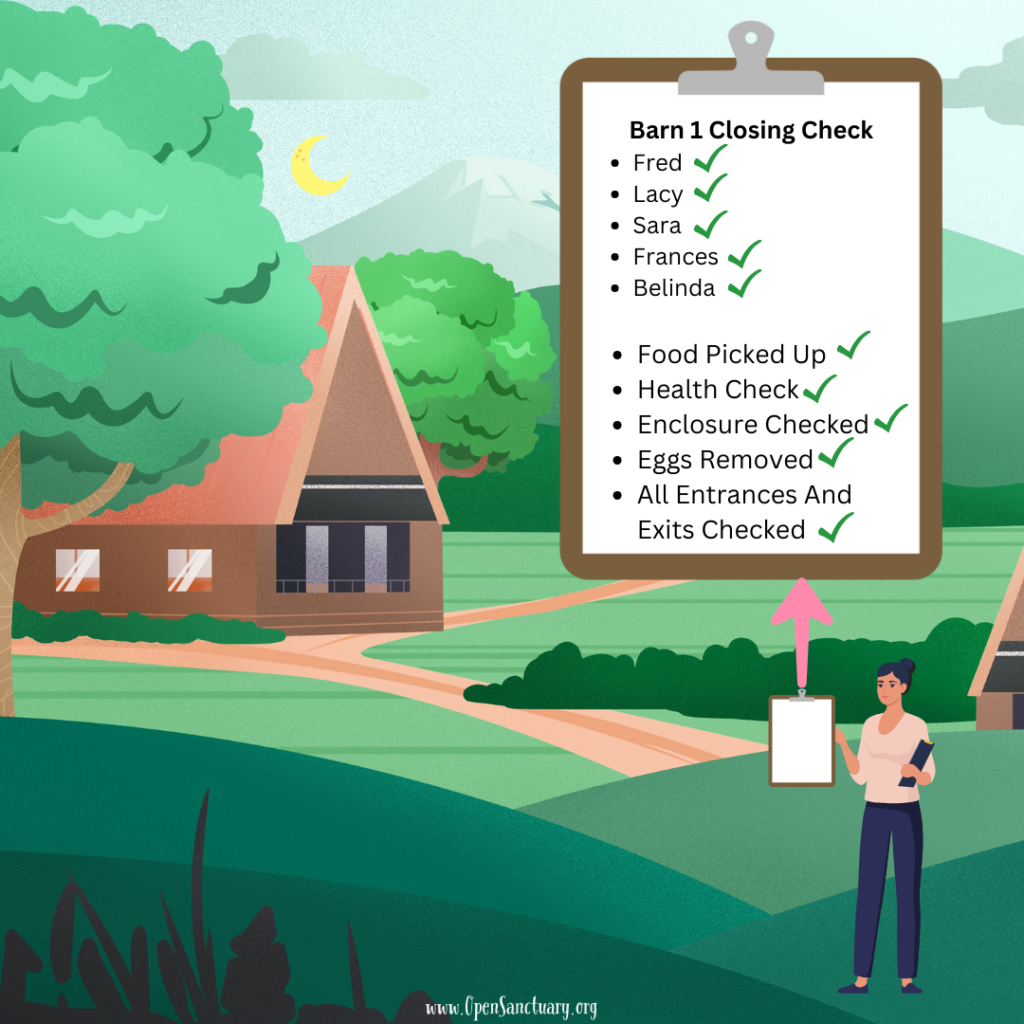

Remember that some predators are initially attracted to your residents’ food, so if not already done, make sure all food has been picked up and put away in tightly sealed bins and that any spilled food has been cleaned up (additionally, food will attract smaller prey species, who in turn will attract predators). Your residents’ eggs may also attract certain wildlife, so if eggs have not already been collected, be sure to do so. It’s also important to take time to look around the space to ensure that a) no predators are being closed into the space and b) that no breaches have developed that need to be addressed (we’ll talk about this more below). When leaving the space, ensure all entry points are closed and securely latched to ensure your residents’ safety overnight.

Consider Making A Closing Checklist!

Caregivers have a lot of things to keep track of. Particularly in settings where a team of folks rotate through closing duties, consider making a checklist to help ensure no steps get missed. As with any checklist, be sure to keep it updated!

Provide Safe Outdoor Settings

When it comes to providing your avian residents with safe outdoor spaces during the daytime, there may be more variation on what you will find necessary, depending on factors such as:

- The species for whom you care;

- The predators in your area;

- And the amount of human presence in the area.

For example, a space that provides ample protection for a group of turkeys may not even be able to keep a small chukar resident contained, let alone safe from predators. Additionally, what is reasonable in a setting where residents are closely supervised may be inappropriate in a setting where residents are left unattended for portions of the day. Therefore, you’ll need to consider what is most appropriate given the specifics of your sanctuary and residents.

We’ll start with some thoughts on measures that we consider to be either insufficient or inappropriate when it comes to providing safe outdoor settings, then discuss the minimum measures you should be taking regarding daytime and outdoor predator protection. Finally, we’ll move on to even more measures you can consider to maximize the safety and well-being of your avian residents when it comes to predator risks in outdoor spaces.

Free Ranging Is Not Recommended

The concept of “free-ranging” comes up often, particularly in backyard chicken settings, but different folks have different ideas of what it entails. We will define “free-ranging” as the practice of allowing residents to roam freely and unsupervised in outdoor spaces that have not been specifically designed with their safety in mind and/or that have not been thoughtfully evaluated and determined to provide reasonable predator protection as described below. While some sources will have you believe that the only way to provide ample room to your residents is to allow them to free-range, this is simply not true. Many farmed avian species are domesticated to varying degrees, thus ill-suited to a free-range life. They are also prey animals, and thus providing them with protected spaces can, in fact, enhance their sense of safety and well-being.

We strongly recommend that outdoor spaces be designed thoughtfully and with predator-proofing in mind, particularly if residents can access these spaces without close supervision. While free-ranging is a common practice, especially in the backyard chicken-keeping community, this practice offers little to no protection from predators and gives you little control over your residents’ environment. Therefore, it is not a practice that we recommend.

Prey Species Attract Predators

Even if you live in an area where you have not seen predators, keeping and caring for prey animals will attract them (and, as mentioned above, will likely attract other prey animals drawn to their food or the environment you create). Loose food that is not picked up, eggs, or just the scent of your residents (who, in all cases of domesticated birds, are prey animals) is sufficient to attract animals who are interested in pursuing further meals, whether it be loose food, your avian residents themselves, or their eggs.

Supervision Does Not Guarantee Safety

Many benefits come with closely supervising your residents, including the ability to engage in close observation, which can give you important insights into their health and well-being. However, we must stress that supervision does not always equal safety, especially in the context of free-ranging. Some predators may steer clear if humans are around, and a human may be able to intervene if certain types of predators attempt to attack residents, but this is not always the case.

Certain types of predators (particularly aerial predators) may be undeterred by human presence and some may be too quick and/or strong for a human to intervene, even if they are close by. Therefore, it’s essential to carefully consider if it is reasonably safe to rely solely on close supervision as a means to keep your residents safe and if, instead, you should provide additional safety measures (such as robust fencing or overhead netting) in order to keep residents protected from predators.

Similarly, while some folks use technology such as cameras to monitor their residents, being able to see a predator threat on camera does not mean that you will be able to intervene in time to protect your residents in the case of a sudden predator attack. Cameras are not protection in and of themselves, although they can help identify predators who may pose risks to your residents, which may provide you with additional insight into the kinds of protection you need to implement.

In short, while there is clearly value to the close supervision of residents and in the use of cameras to monitor them and their environment, neither of these measures are inherently protective and should be considered alongside and with the use of protective physical infrastructure.

What About “Flock Guardians?”

It’s not uncommon to come across sources suggesting that avian residents can safely free-range if they live with a “flock guardian.” For example, some sources may suggest the inclusion of a “livestockAnother term for farmed animals; different regions of the world specify different species of farmed animals as “livestock”. guardian” dog (“LGD”) to help keep avian residents safe. Unfortunately, not only is this NOT a fail-safe method of predator protection, but dogs, even “trained” LGDs, can also harm avian residents. While there are certainly examples of a particular dog and avian resident getting along, there are also many reports of dogs going after bird residents, sometimes with little to no warning. Even if the dog doesn’t go after avian residents, they may still be perceived as a threat, causing avian residents distress. Additionally, a dog is no match for certain predators and could be at risk from harm themselves.

Employing LGDs To Kill Wildlife Is Unacceptable

Even if a dog is capable of consistently “defending” their flock, it is also important to consider the safety and well-being of wildlife. Co-existing with wildlife in a way that is safe for both wildlife and your residents is possible, but is quite a different thing from treating wildlife as enemies or foes to be battled. In a sanctuary context, we must remember that the lives of wildlife are not “less than” the lives of our residents. Wildlife has every right to share their ecosystem with us, and it is our responsibility to make sure we protect our residents from harmful interactions while also taking steps to avoid harm to wildlife. Using animals such as LGDs to kill other animals is unacceptable. At The Open Sanctuary Project, unacceptable means that we cannot condone (or condone through omission) a certain practice, standard, or policy. See a more detailed explanation here.

Another fairly common recommendation is to rely on certain avian residents to protect other avian residents. In these situations, the recommendation may be to rely on a larger species to protect a smaller species (for example, relying on geese or turkeys to protect chickens), or a source may suggest that one can rely on a rooster to keep hen residents safe. As with the inclusion of a guardian dog, relying on certain avian residents to protect others is not a reliable form of predator protection.

In addition to the likelihood of “protected” residents being harmed despite the inclusion of a “guardian” in their living space, the avian “guardian” is also at risk of severe injury or death. Unfortunately, this is especially common with roosters, who are often loyal protectors of their companions, putting themselves in harm’s way to protect their loved ones. While roosters may willingly take on the role of protector, they should never be put in a position where they are the only line of defense between other residents and predators, nor should they be in a situation where they do not have proper protection themselves.

Consider as well the question of whether it is appropriate to “use” one resident for protection purposes in a sanctuary context. Philosophically, such “use” can cause both direct and indirect harm to the guardian animal. Bottom line – we believe that there is simply no substitute for proper housing and fencing when it comes to predator protection, and living arrangements should be informed by the needs of each individual resident, not the role we feel they should play.

Basic Predator Protection For Outdoors And Daytime Spaces: Consider Your Residents, Your Environment, And Your Predator Population To Find The Best Options

Regardless of the species in your care, it’s essential to be thoughtful about when, where, and how your residents spend time outside to ensure their safety from predators. However, what exactly this entails may vary from sanctuary to sanctuary or even within one sanctuary.

When determining what is most appropriate for your residents, be sure to revisit the risks you identified earlier – which predators are a concern during the day? How might they gain access to your residents? Are your residents most vulnerable to digging, climbing, aerial attacks, or all three?

Also, while we note above that supervision is not a protection in and of itself, it can also be helpful to consider the amount of human presence during times when residents are in their outdoor space. Will they be closely supervised? Will humans be nearby doing other things but able to check in regularly and hear alert calls or commotion? Or will the humans be off-site, unable to keep close tabs on residents?

Other factors, such as your residents’ flight abilities, may also come into play. Some species may do well with robust fencing and close supervision, while others may require the addition of aviary netting or a fully enclosed aviary. There will also be variation due to differences in the size or type of space provided. Materials that work well for a small, short run may not work well for a larger space that needs to accommodate humans coming and going from the space.

The answers to these questions and others should help inform your decisions about outdoor accommodations. Below, we’ll look at the major infrastructural components you should consider when designing an outdoor space for avian residents.

Secure The Perimeter Of Outdoor Areas With A Protective Barrier Or Fence

Whether residents are supervised or not, we recommend providing some sort of fencing or barrier to define the space and keep residents in. A fenced area by itself offers the minimum amount of protection for your residents necessary (and no protection against aerial threats). However, depending on your unique situation, a fenced area may provide all the protection your residents need. This may be due to your residents’ species/size or because they only have outdoor access while closely supervised (though we do want to stress again that not every predator is deterred by human presence, and so supervision is not sufficient predator protection by itself).

If you are considering this setup for your residents, it’s essential to recognize that not all fencing is created equal. The most appropriate materials to use for your protective barrier will depend on factors such as the species, the predator risks, the size of the area, etc. Options include but are not limited to, materials such as:

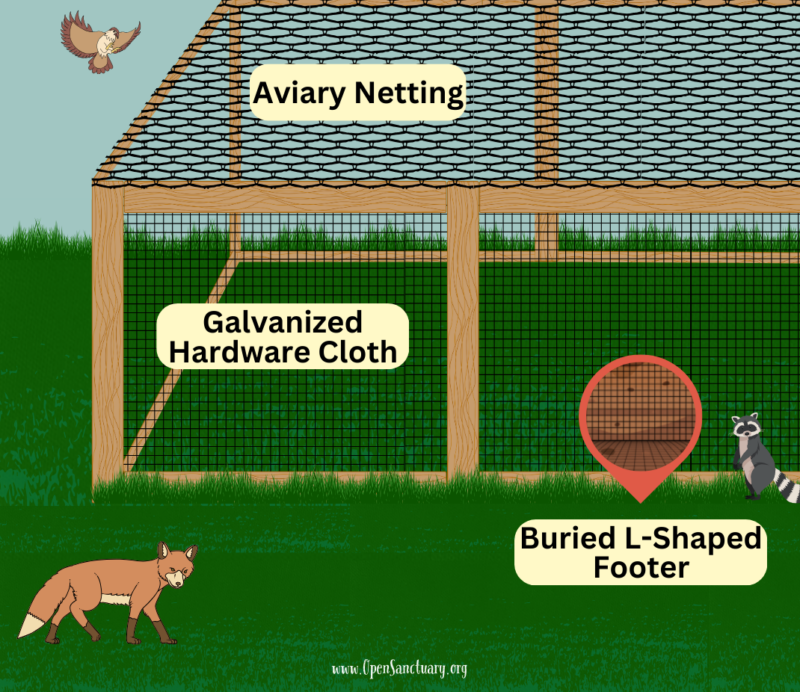

- Non-climb galvanized wire mesh fence secured to wood and/or metal fence posts (as with galvanized hardware cloth, this comes with various size openings, some of which may be entirely too large to be protective – 2×4” is common, but may not be appropriate for smaller species or in areas where smaller daytime predators are a threat).

- More protective materials, such as galvanized hardware cloth, which can be used in conjunction with other materials (such as non-climb fencing or welded wire kennel panels) or can be framed with wood boards to create fence panels.

- Modular welded wire panels (such as dog kennel panels). Unlike fence installation, which may require hiring a professional or learning a new skill yourself and investing in appropriate tools, this setup can be put up fairly easily without any fencing experience or special equipment. As with traditional fencing, you’ll want to consider how tall the panels need to be. If the grid openings are too large, you could wrap the panels with galvanized hardware cloth or netting to provide more protection. Additionally, these panels often have short feet that raise them slightly off the ground. They therefore may need additional fortification along the bottom to prevent predators from squeezing or digging under.

Chicken Wire Is Not Recommended!

While there are multiple materials to consider, one we absolutely do not recommend is chicken wire. This material can be easily torn, crushed, and circumvented by a predator and will NOT keep your residents safe from predators.

When determining the best materials to use when creating the perimeter of the space, be sure to consider the following factors:

- Perimeter Height –

- If you don’t plan to cover the top, how tall must the perimeter be to keep residents in and deter predators who jump or climb? When considering fence height, remember that predators such as foxes can easily climb or jump a 4 or even 5-foot fence. Similarly, certain sanctuary residents may be able to fly over a fence of this height. If providing a fenced space when residents are not supervised, an 8-foot fence will provide more protection against certain climbing and jumping predators, but still will not protect against aerial threats and may need modifications to prevent coyotes from climbing over it.

- If you do plan to cover the top, how tall does the perimeter need to be to comfortably house residents and other elements of the space (such as perches and vegetation)? If caregivers need to enter the space physically, consider how high off the ground the top needs to be for them to do so comfortably.

- Gap Size – While not every species and setting will require adherence to our overnight rule to cover any opening larger than a U.S. quarter, you’ll still need to consider how large any openings in the material can be while still keeping residents safe.

- Sturdiness, Strength, and Longevity – You will want to think about weather conditions in your area and what kind of materials will hold up based on these environmental factors. Also, consider the predators in your area and how strong the materials must be to deter them.

Covered Spaces: Their Benefits And Limits

Some sources suggest that providing covered areas within a fenced space (or unfenced, in the case of free-ranging) will provide ample protection against aerial threats. These sources suggest that when bird residents detect an aerial predator, they will run for cover, foiling the predator’s plans. While it is true that birds may seek cover when an aerial threat is detected, this is NOT a fail-safe method of predator-proofing. Some predators may still be able to reach a bird resident or may sit in wait until they come out again. The best way to protect against aerial threats is to use aviary netting or something similar to prevent aerial predators from accessing outdoor spaces. We will discuss this further below! However, while netting or galvanized hardware cloth will keep aerial predators out, it may still leave residents feeling vulnerable if they do not have areas of solid cover. Therefore, we recommend adding non-toxic tall vegetation (particularly evergreens for year-round coverage) and/or man-made protective structures to the space as well. While these elements on their own may not fully protect residents from predators, they will provide a sense of safety and add interest and enrichment to the space, giving your residents options to choose between regarding where they spend their time. Check out our resource on animal-centered design for more information and inspiration!

Deter Digging

In addition to a strong perimeter, you’ll want to consider the risk of digging threats (and remember that other animals who do not pose a predation risk may dig under the perimeter, creating an entry point for predators). This will depend on the specifics of your situation (including the size of the space and the amount of human supervision).

In some specific situations, digging may be less of a concern. For example, consider a caregiverSomeone who provides daily care, specifically for animal residents at an animal sanctuary, shelter, or rescue. who lives with a house rooster, who brings the bird outside only under direct and constant supervision. In such a case, a simple run made of dog panels or an X-pen may be sufficient to protect the rooster on his outdoor expeditions.

However, in virtually any situation where birds spend most of their time outdoors, you will want to take steps to prevent anyone from digging under the perimeter. This can be accomplished in various ways, including:

- Adding a galvanized hardware cloth apron/skirt to the outside of the perimeter;

- Or bending the base of fencing outward into an “L” shape and burying it.

Avert Aerial Attacks

Once you’ve determined the most appropriate fencing for your avian residents and sufficiently protected them from diggers, it’s time to consider the best way to protect them from aerial threats. As mentioned above, fencing alone will not protect against aerial threats. Instead, you may need to cover the top or create a fully enclosed aviary. We’ll discuss both options in more detail below.

Fencing Plus Aviary Netting

One common strategy for protecting residents against aerial threats is to cover the top with a protective material that will act as a barrier between residents and an aerial predator. Depending on the size of your enclosure, different kinds of materials may be appropriate. These may include:

- Screening material, such as those used in screen doors and windows. This light material may be more easily used and manipulated to cover smaller areas, but remember that it can be torn easily and should be frequently checked for breaches.

- Plastic tarps. These materials are also protective from an HPAI protection perspective since they will exclude wild bird poop from enclosures. However, if they are used to create a flat overhead covering to a fenced area, they can hold rain and snow, which can potentially cause them to collapse and harm residents. Tarps can also crack from prolonged exposure to elements or be torn by predators, so they should also be frequently checked.

- Netting marketed specifically for covering avian enclosures such as 3T products. Some sanctuaries have successfully used such netting in conjunction with tension wire and 4×4 support posts, which have proven helpful in supporting it in snowy conditions.

- Other netting products such as golf netting or camouflage netting, although these may present risks to wildlife such as songbirds.

Netting And Snow

In determining the appropriate netting material for your outdoor avian resident areas, the climate will be an important consideration. While many kinds of netting can work well to enclose pens, in climates with heavy precipitation and snow, ice and snow can weigh down and damage it or even cause it to collapse on your residents, which can be very dangerous. This can happen with even the largest mesh! In areas with light snowfalls, meticulously brushing off snow from netting or tarps may be sufficient. However, in areas with heavier snow and ice, ensuring ample support for netting is important, and as mentioned above, when using netting marketed specifically for avian enclosures, you can also purchase tension wire that can help alleviate tension on netting weighed down by snow and thus prevent damage. This can be combined with pully mechanisms that can help loosen net tension and dump the snow load, or roll netting up at night to be re-engaged during the day.

Be Conscious Of Songbirds And Other Wildlife

While netting helps exclude aerial predators from your residents’ outdoor spaces, it can also pose a hazard to other wild living birds, such as songbirds, who can become entangled and trapped in netting. While camouflage netting in particular, creates a more “natural appearance,” it can trap wild birds easily and be difficult for them to escape on their own. Some sanctuaries have been able to strike a balance between protecting residents and avoiding harming wild birds by using netting with 2-inch gaps, which seems to be sufficiently small to deter aerial predators and sufficiently large to prevent trapping most songbirds and other wild birds. In any case, checking netting for anyone who may have become trapped is a crucial task to do regularly.

A Fully Enclosed Aviary/Run

Depending on the species you care for, the predator threats in your region, and the amount of human supervision provided, you may need to provide an even more protective environment. In areas with highly active aerial predators or predators who are adept at and prone to climbing enclosures and fencing, a fully enclosed aviary may be the most appropriate option. You may also opt to create both a fully enclosed aviary and a fenced area, giving residents access to one or the other depending on whether or not they are closely supervised.

Creating fully enclosed aviaries and runs may be a more expensive option and may limit the size of the space, but when properly constructed, they will fully protect your residents from aerial predators as well as those who can climb or jump over fences (though you must make sure the materials are sturdy enough to withstand the weight of these predators). The type of materials you use will be dictated by which predators you are trying to keep out. If, for example, your concern is raccoons, you can likely use materials such as galvanized hardware cloth reinforced into panels with wooden boards as support beams. However, if you are concerned about bears, you must provide a much sturdier structure. Clear PVC roofing or even metal roofing may become necessary if heavier climbing predators frequent your area.

What About Predator Deterrents?

The focus of this resource is physical infrastructure that will deter a predator’s attempts to gain access to avian residents, but other types of deterrents, such as those that are thought to scare predators away or otherwise discourage them from coming near avian residents often come up in discussions of predator protection as well. Predator deterrents such as motion activated lights at night, sprinkler systems, and owl or other predator decoys are often suggested as a means of predator protection in many contexts, and especially in backyard chickenThe raising of chickens primarily for the consumption of their eggs and/or flesh, typically in a non-agricultural environment. farming contexts. While these kinds of measures are not inherently harmful (as long as they do not alarm or harm your residents in their living spaces, or harm wildlife), they too cannot be considered predator protection in and of themselves. However, even in fully predator-proofed spaces, predators may still approach your avian residents, which could cause them extreme distress and could even result in injury if residents panic and attempt to flee. Because of this, predator deterrents such as those listed above MAY be useful since they could deter predators from approaching avian resident living space, but only in conjunction with the use of effective infrastructure.

When thinking about if and how these types of deterrents fit into a sanctuary setting, it’s important to first recognize that, as with close supervision and cameras, they are not a substitute for proper predator protection such as robust overnight accommodations and secure fencing. Additionally, while some deterrents may be more effective than others, in general, these types of deterrents are rarely effective in the long term due to habituation (wildlife may be initially fearful of a new deterrent, but will likely become used to it over time). Ultimately, we have found that the combination of being mindful of where you site avian living spaces, avoiding practices that attract wildlife (such as leaving spilled food down overnight), and creating protective physical infrastructure to be much more effective than attempting to scare or otherwise discourage wildlife from coming near avian living spaces. In addition, we need to note that the use of deterrents such as coyote urine, fox urine, or other products of predators who have been exploited are unacceptable for use in sanctuary contexts. At The Open Sanctuary Project, unacceptable means that we cannot condone (or condone through omission) a certain practice, standard, or policy. See a more detailed explanation here.

Regularly Inspect Living Spaces And Conduct Maintenance As Needed

Once you have your predator-proof space, it’s important to inspect the space and conduct maintenance as needed regularly.

Regular Inspection

Through regular inspection of the space, you are more likely to catch breaches before disaster strikes. You may also be able to detect areas that have not yet developed a breach but appear to be weakening. We strongly recommend incorporating a brief inspection of overnight accommodations into your closing routine to address any breaches. If a permanent or temporary fix is not immediately possible, other steps should be taken to keep residents safe, such as moving them to a different space overnight. During closing inspections, the following are particularly important to note:

- Make sure windows either close and lock tightly or are fully and securely covered with galvanized hardware cloth.

- Ensure all doors close tightly, are free from gaps around them, and latch/lock securely (and that latches can not be easily opened by a raccoon).

- Visually inspect any hardware cloth-covered openings to ensure that hardware cloth is still in place and secure.

- If the space has an exhaust fan, ensure the locking louvers work properly.

While it’s important to check for breaches when closing up residents in the evening, the reality is that certain parts of the living space cannot be easily evaluated when full of bedding and other elements. Therefore, we recommend also checking for breaches (or developing breaches) during habitat cleaning, when bedding, perch bales, and other elements are removed from the space. Be sure to frequently check underneath perch bales and behind nesting areas or other areas where a breach could be hidden. You should also regularly inspect around the foundation of the structure for signs of digging.

It’s also important to regularly inspect outdoor spaces. For example:

- Check that perimeter fencing has not developed a breach. If you have not incorporated an apron or skirt to deter digging, be sure to check closely for signs that someone has been or is attempting to dig under the fence. Similarly, watch for areas where the ground may be eroding, creating gaps under the perimeter.

- If you have added a digging deterrent, be sure to check that it continues to be in place. Hardware cloth that has not been buried may start to bend or curl, allowing digging threats to gain access to the space.

- If you have added netting, tarps, or screens to the top, be sure to check for tears or areas where it has become detached from the perimeter. If tarps become stiff or start to crack, they should be replaced or reinforced, as a breach is likely.

Any breaches or areas of weakening protection should be immediately addressed. In some cases, this will involve a temporary fix to fortify your defenses until a more permanent solution can be implemented.

Maintenance

Depending on the materials used, you may need to schedule routine maintenance and/or replacement of these materials. For example, to prolong the life of certain types of wood, you may have to restain or repaint them using safe products for avian residents. Be sure to consider what types of routine maintenance are necessary, and put them on your calendar so they don’t get missed!

Conclusion

Predator protection requires a combination of advanced planning, infrastructure building, and day-to-day maintenance. You must learn about your environment, carefully consider your residents’ abilities and vulnerabilities, carefully plan infrastructure and caregiver capacity, and undertake day-to-day monitoring of infrastructure and the environment. Providing safe sanctuary to farmed birds, keeping in mind their status as prey animals and ensuring that they are free from threats from predation, is critical to providing them with long-term safety from harm, stress, and fear.

Action Steps:

- Research predators that inhabit your region

- Use your observation skills and tools, such as motion-triggered cameras, to familiarize yourself with the predators who travel through or live on/near sanctuary grounds (recognizing that even if you do not detect signs of predators, you still must assume they are present or could be in the future).

- Use your knowledge about your environment to make strategic siting decisions for avian living spaces.

- Assess your existing overnight infrastructure to ensure it is impenetrable to breaches by predators, or build infrastructure that is.

- Based on your assessment of predator risks, use infrastructure such as fencing with buried protective perimeters, overhead netting, or fully enclosed aerial netting to make sure your residents’ outdoor living spaces are secure from climbing, digging, chewing, or aerial predators. Choose your materials strategically to address all potential risks.

- Use protocols such as “closing lists” to check the security of your overnight living spaces each night when you close birds into these spaces.

- Use protocols, such as checking for breaches during routine cleaning and maintenance, to ensure your predator protection remains fully intact.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Triangle Chicken Advocates and Rooster Haus Rescue for their contributions to this resource and for their thoughtful review.

SOURCES:

Compassionate Wildlife Practices At Your Animal Sanctuary | The Open Sanctuary Project

Advanced Topics In Avian Health: Avian Influenza | The Open Sanctuary Project

Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza: Your Sanctuary And The Law | The Open Sanctuary Project

Sharing Your Home With Chickens | The Open Sanctuary Project

Understanding Your Animal Sanctuary’s Zoning Rights And Restrictions | The Open Sanctuary Project

Signage To Consider Implementing At Your Animal Sanctuary | The Open Sanctuary Project

Creating A Good Home Series | The Open Sanctuary Project

Preventing Foreign Body Ingestion At Your Animal Sanctuary | The Open Sanctuary Project

Backyard Chicken Recommendations In Sanctuary: A Word Of Caution | The Open Sanctuary Project

The Caregiver’s Guide To Developing Your Observation Skills | The Open Sanctuary Project

Introduction To Rooster Behaviour Part 1: Dismantling Rooster Stigma | The Open Sanctuary Project

Avoiding Harm To Animals At Your Animal Sanctuary | The Open Sanctuary Project

Learn About North America’s Song Dog | Project Coyote (Content Warning: Graphic Images)

Bobcats | The Nature Conservancy

Mountain Lions: Frequently Asked Questions | The Mountain Lion Foundation

Extra Heavy Knotted Netting | 3T Products

Predator Management For Small And Backyard Poultry Flocks | Poultry Extension (Non-Compassionate Source)

Protecting Small Poultry Flocks From Predators | Oklahoma State University Extension (Non-Compassionate Source)

Red Fox | Connecticut Department Of Energy & Environmental Protection (Non-Compassionate Source)

Common Snapping Turtle | Connecticut Department Of Energy & Environmental Protection (Non-Compassionate Source)

Badgers | Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit US Fish and Wildlife Service University of Wyoming (Non-Compassionate Source)

Managing Predators | Jacquie Jacob (Non-Compassionate Source)

Management Of Waterfowl | Clinical Avian Medicine (Non-Compassionate Source)