You may have read our resource on identifying abnormal behaviors in residents. If so, you’ve hopefully gained a better understanding of what abnormal behaviors are, the different kinds of abnormal behavior, and what might be causing them. It might be a good place to start if you haven’t read it yet! In this resource, we will briefly review causal factors that may contribute to the development or persistence of abnormal behaviors. The main focus of this resource is how to lower the risk of residents developing abnormal behaviors and how to manage, reduce, or stop the abnormal behaviors altogether. Let’s review common causes of abnormal behavior first:

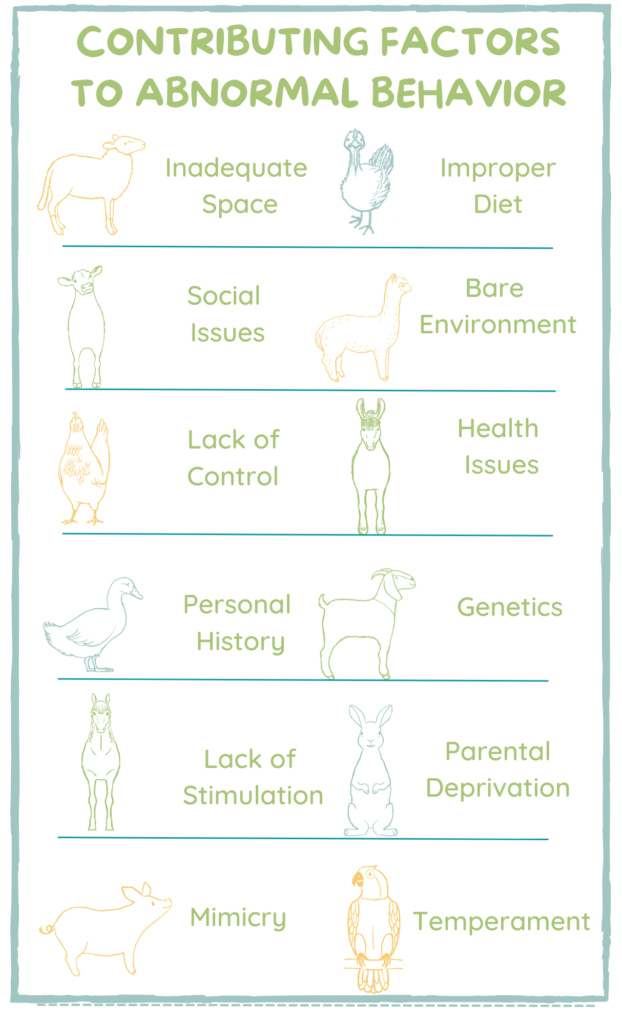

Possible Contributing Factors

To effectively troubleshoot what might be causing residents to behave in abnormal ways, we first have to understand what is typical for each species and each individual. This doesn’t just mean what behaviors are normal but what diets, environments, time budgets, and social relationships are normal. Additionally, it is helpful to learn whether breed characteristics or genetic factors may predispose some individuals to certain health issues or behaviors. Take a look at the illustration below to see some example contributing factors:

How To Lower The Risk

While it isn’t possible to change an individual’s past experiences or genetics, there are many ways you can reduce the risk of residents developing abnormal behaviors. It is also possible in some cases to reduce or completely extinguish the prevalence of some already existing abnormal behaviors in individuals. So much is influenced by environmental factors, although genetics, life experiences, and health come into play. The good news is that you can usually do something about environmental factors and ensure residents receive appropriate and timely medical care. Let’s break them down and address how you can approach each in a way that can lower the risk of residents developing abnormal behaviors. Above all, the strategies aim to meet the residents’ needs and provide a home that encourages natural behavior and positive experiences.

Diet

Diet can greatly affect a resident’s physical and psychological health. Residents should be given a species-appropriate diet that allows for and encourages natural eating behaviors that resemble a natural diet as much as possible and meet their nutritional needs. Always consult a veterinarian when trying to determine an appropriate diet. Dietary factors you can often control include the type of food, when to feed them, where to feed them, how much to feed them, how many times to feed them, and offering nutritional enrichment. Diets gobbled up in minutes often leave resident species with a lot of extra time they would typically spend in foraging and eating behaviors. This can increase the risk of certain abnormal behaviors. Here is a list of dietary factors that can help keep residents happy and healthy:

- Species-appropriate

- Meets behavioral needs (goats browse, chickens scratch around)

- Appropriate amounts

- Meets nutritional requirements

- Healthy ratios (In many farmed mammals, offering diets heavy in concentrates can lead to health issues and the development of abnormal behaviors. Speak with your veterinarian about the ideal ratios for each individual.)

- Nutritional enrichment

- Multiple feedings spread over the day

Example: Isabelle

Background

Isabelle and Cindy are new sheep residents. In fact, they are the very first sheep residents to have a home at the sanctuary, and their rescue was rather sudden. Isabelle and Cindy are currently quarantined before moving to their new living spaceThe indoor or outdoor area where an animal resident lives, eats, and rests.. They have access to both indoor and outdoor living spaces during the day. The indoor space comprises a 10 x 10 pen area with rubber mats, two rubber food bowls, and a water trough. The outdoor living space is a small paddock made up of dirt, a few patches of dried grass, a tree, and a small mound. For their diets, they receive primarily concentrates and 1 flake of hay each in the morning, a treat of carrots or celery as a snack in the afternoon, and another flake of hay in the afternoon. Staff also provide sensory enrichment in the form of putting sheep-safe spices in different areas of their living space to encourage exploration.

Behavior

After a few days, a caregiver notices that Cindy is missing a bit of wool on her back right side but isn’t sure if she came in that way or not. They make a note in her file and ask the other caregivers if they knew whether the missing wool was new or not. They also don’t recall, and the picture in her file only shows her face and left side. A couple more days go by, and sure enough, Cindy is now missing more wool. They search around to see if her wool is catching on something in the environment, and a volunteer tells a caregiverSomeone who provides daily care, specifically for animal residents at an animal sanctuary, shelter, or rescue. that they saw Isabelle pulling on Cindy’s wool and eating it.

Causal Factor

Why in the world is Isabelle eating Cindy’s wool? They seem to get along okay. Maybe she is missing something from her diet. The caregivers call their vet and research sheep behavior as they haven’t previously cared for sheep. One caretaker had done a brief search when they were told they were taking in new sheep residents that week and found the diet recommendation they were following on a blog somewhere. After speaking with their veterinarian and finding more reliable sources, they discovered that sheep should be offered a diet high in forage, with limited amounts of concentrates, if needed.

Possible Solution

They decide to try this more appropriate diet before separating the residents because they know how important having a companion is for social species. They begin offering free choice forage and significantly reducing concentrates.

Outcome

Success! Changing their diet proved to resolve the situation immediately. Caregivers kept a close eye on the two residents and continue to do so but haven’t seen any further signs of wool-biting.

Living Spaces

Where a resident lives can affect their psychological and physical health. Species-appropriate housing should provide shelter, safety from predators, resources (food and water), and enough room to move about comfortably, exercise, avoid conflicts, and include other elements that encourage natural behaviors. Living spaces that are too small, too crowded, unsafe, bare, and lack appropriate shelter, species-appropriate landscape features, and access to resources can contribute to the development of abnormal behaviors. Overcrowding can increase confrontationalBehaviors such as chasing, cornering, biting, kicking, problematic mounting, or otherwise engaging in consistent behavior that may cause mental or physical discomfort or injury to another individual, or using these behaviors to block an individual's access to resources such as food, water, shade, shelter, or other residents. behaviors, stressing residents out and contributing to injuries and the development of unnatural behaviors. Instead, living spaces should ideally:

- Have plenty of space in terms of population and freedom to explore and exercise

- Be free from dangerous elements such as toxic plants, broken/improper fencing, predators, and items that could lead to foreign body ingestion

- Contain natural or constructed elements that mimic their natural environment and encourage natural behaviors

- Have private areas where residents can remove themselves from stressful situations or act as visual barriers

- Contain materials that encourage natural behaviors, such as those for nest building

Example: Nisbet

Background

Nisbet is a rabbit resident whose living space consists of a standard rabbitUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated rabbit breeds, not wild rabbits, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource. cage, bedding, a waterer, all the timothy hay she wants, daily fresh leafy greens, a cardboard house, and chew toys that are changed each week. She also has a little ramp leading out into a 5 x 5 pen area with a tunnel, a blanket, and a ball.

Abnormal Behavior

Although Nisbet can be seen eating and drinking regularly, using her tunnel, and occasionally chewing on a toy, she also spends a significant amount of time in the corner of her living space frantically digging at the floor. This behavior had been going on for weeks. Her caregivers are concerned. It appears to them that Nisbet’s environment is lacking and not meeting her needs. After a health check to ensure there isn’t anything physically wrong, her caregivers sit down and list what might be negatively affecting Nisbet.

Causal Factor(s)

They noted that rabbitsUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated rabbit breeds, not wild rabbits, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource. are natural diggers and dig and make their home in burrows and that rabbits are social animals and ideally should have a companion. These were two areas lacking for Nisbet and could contribute to her stress and the stereotypy of corner-scratching. Nisbet is a normal rabbit in an inadequate environment.

Possible Solution

Once care staff provided Nisbet with a special digging box and introduced Celia, another rabbit resident, to a living space near her (hoping to join their living spaces), the behavior was significantly reduced. It was something they observed just a few times in the following months. Now Nisbet can be seen digging in her “dig box” and positively interacting with Celia. While Celia wasn’t exhibiting abnormal behaviors, her caregivers have noticed she interacts and explores her living area much more and is seen playing with Nisbet.

Outcome

Success! Sometimes there is more than one causal factor contributing to the abnormal behavior. By ensuring Nisbet had her social and digging needs met, the frequency of the abnormal behavior was significantly reduced.

Health Care

Ensuring residents are physically healthy is important for their psychological health too. Depression, anxiety, frustration, and high-stress levels can result when physical health needs are unmet. All residents should receive a thorough intake evaluation, regular health checks, and daily observations to ensure illnesses and injuries are identified and addressed as soon as possible. Sometimes abnormal behaviors can result in physical health conditions. An example is a resident with an external parasite problem who continuously rubs part of their body against a wall or post to scratch an itch. This, in turn, can cause further health issues. Keeping residents healthy requires:

- A thorough intake evaluation

- Regular health checks

- Injury prevention (safe living spaces and stable social groups will reduce injuries)

- Daily observations

- Rapid identification and treatment of issues

- Staff training on how to properly perform health checks and identify issues

- Consulting a veterinarian to address health concerns

- Proper diet

- Daily movement

Example: Henrietta

Background

Henrietta is a gregarious brown hen who lives in a small flock with three other chicken residents. They have access to both their indoor and outdoor living space during the day. Their outdoor space is a 15 x 10 covered area that prevents contact with wild birds (See our resource on HPAI) and provides protection from predators. They have a dust bathing area, a couple of logs to hop on, a ladder for roosting, and some bushes for hiding. Henrietta is often the first out the door and the last one in at night. She likes exploring her environment, especially when caregivers provide enrichment!

Abnormal Behavior

Recently, care staff noticed Felicity, Toby, and Lexi made it out the door first thing in the morning. Henrietta wasn’t far behind but had taken a moment to preen herself. They watched her scurry out after her friends and saw that she was moving well and excited about breakfast. Later in the morning, her caregiver came in to switch out waterers for cleaning and noticed Henrietta was again preening herself. So was Felicity. Even later, when they brought nutritional enrichment (a hanging cabbage for them to peck at), Henrietta was yet again preoccupied with preening. The caregiver knew that sometimes preening can be a redirected behavior when a resident is torn between two desires, but that didn’t seem to be the case here. Concerned, her caregiver gave her a quick health check and found poor Henrietta had mites. This could definitely explain the over-preening behavior.

Possible Solution

The caregiver radioed other care staff, and that afternoon they treated the whole flock for mites.

Outcome

Success! Soon Henrietta was back to her old self, practicing a normal amount of preening and enjoying her days.

Social Relationships

A solid understanding of a resident species’ social dynamics and needs helps caregivers meet these needs. Without this knowledge, it is easier to make mistakes when housing residents together. What does a particular species need to prevent serious confrontations? (A resident communicating their comfort level, or lack thereof, to another resident isn’t often something to be concerned about. This might look, or rather, sound like Petunia, a pig resident, squealing when Pan bumps into her on their way to get breakfast.) Is there a social hierarchy that needs to be considered? What is the best way to introduce a new resident to the group? How do social needs change if someone has a baby? (Read our Why Residents Shouldn’t Breed At A Farmed Animal SanctuaryAn animal sanctuary that primarily cares for rescued animals that were farmed by humans. resource here.) Are there residents who are bonded? Are there too many residents in this living space? Overcrowding can contribute to abnormal behavior, such as tail-biting and belly-nosing in pigs. Remember to consider the individual as well as their species. In terms of social relationships, you should:

- Observe social group dynamics daily

- Identify possible causes of social distress

- Provide multiple sources of water, food, enrichment, and hiding areas

- Rethink resident groups and consider multiple groups to ensure harmonious interactions

- Keep bonded companions together

- Whenever possible, avoid isolating social residents

- Provide visual access to others of their species when residents must be separated

- Provide temporarily isolated residents with a companion

- Be sure mothers have the space and resources they need to care for and protect their young (or fathers in the case of emus)

- Be sure young residents are raised by their mothers or an adoptive parent of their species whenever possible

- Be aware of season-specific reproductive challenges, such as those with duck residents. (Drakes often become hyperfocused on mating, and alternative living arrangements may need to be considered for a time to ensure the safety of hens and even particular drake residents)

- Build a relationship with them by spending time outside potentially stressful interactions. Patiently build trust using positive reinforcement.

Example: Gideon

Background

Gideon is a placid 12-year-old Quarter Horse resident. He lives in a large pasture with several shade trees, grass, and room to run, along with four other horse residents. Out of all the horses, Mia is his close companion. They spend most of their time with one another and can be seen grazing together and grooming each other. One day a caregiver notices a cut on Mia’s foreleg. She does a brief health check and finds the area a little swollen and hot. She calls the vet and walks Mia out of the pasture to wait for the vet’s visit. Gideon follows along the fence line. The vet arrives and treats Mia’s leg but recommends she stay in her stall for the next week. Gideon whinnies as they walk away, and they let him come in for the night. The next morning, after breakfast, the horses are turned out into the pasture as is their routine. Mia stays behind to rest her leg.

Abnormal Behavior

A volunteer mucking out stalls hears Gideon whinnying and sees that he is frantically pacing back and forth along the fence line. The volunteer calls the care staff, and a caregiver comes out to check on him. He is like a totally different horse. You can see the whites of his eyes, his ears are pricked forward, focusing on something in the distance, and he won’t stop pacing and whinnying. His caregiver can’t seem to get him to calm down, and other staff members are called in.

Possible Solution

One caregiver wonders aloud if there might be a predator nearby, but as they look around, they don’t notice anything strange. The other horse residents are grazing and occasionally looking their way to see what raucous is about. At that moment, Mia whinnies, and Gideon whinnies back. Aha! The abnormal pacing must be due to his distress that he is separated from Mia. While Mia must remain separated from the others, this doesn’t mean she can’t have contact with Gideon. Staff carefully let Gideon into the paddock, where he trots straight for their stalls, slowing as he sees Mia’s head sticking out of her box window. His pacing immediately stops, and after a few minutes, his breathing has slowed, and while not entirely his usual self, he seems much more relaxed. For the next week, care staff will let Gideon in the paddock area so he can have physical and visual contact with Mia.

Outcome

Success! Gideon stops pacing, and after a week, both he and Mia return to the pasture with their herd mates.

Stimulation

While providing for the basic physical needs of residents is vital for their survival, ensuring they have interesting lives and are adequately stimulated is also incredibly important. A lack of mental stimulation leads to boredom, and boredom can lead to the development of abnormal behaviors. Keeping residents engaged through enrichment opportunities is an important part of their care. This can be accomplished in several ways, a combination of which is even better:

- Provide enrichment regularly to residents

- Sensory enrichment – sights, sounds, smells, tastes, and textures (Engage the senses using resident-safe spices, quiet musical experiences, interesting visuals, different substrates to touch, and more.)

- Social enrichment – opportunities to engage in social relationships (There are more ways than you might think!)

- Nutritional enrichment – tasty treats offered in exciting ways (Hanging baskets, browse, hidden snacks, puzzle feeders, and rooting boxes are all possibilities.)

- Physical enrichment – species-specific dynamic surroundings that encourage exploration and natural behaviors (Tall grasses, bushes, boulders, pools, stairs and platforms, dust bathing areas, scratching posts, and many other elements can go a long way.)

- Cognitive enrichment – engage the brain (Puzzle feeders, caregiver-resident positive reinforcement learning opportunities, games, and moderately challenging experiences can all get those wheels turning.)

- Provide novel experiences

- Switch things up a bit. Add something positive and different from their daily experience to keep things interesting.

Be sure to carefully observe resident reactions and remove or adjust any offered enrichment that makes a resident fearful or upset.

Example: Chen

Background

Chen, an active pig resident, loves to explore his outdoor living space and can often be seen rooting around. His outdoor living space has a wallow, shade trees, old logs, grass, and other pig-safe plants. His indoor living space consists of a 10 x10 area that he shares with Becca, with an automatic waterer, rubber food bowls, and rubber mats to lay on. On most days, care staff brings them a treat of blackberries and zucchini or green beans, which they put in their rubber bowls. These treats are soon eaten. Lately, the weather has been extreme enough that caregivers often must keep residents inside.

Abnormal Behavior

After being inside for two days, caregivers notice Chen seems restless, often lying down to get back up again. The weather has limited Chen’s ability to explore, and he doesn’t have the usual space and dynamic environment to engage with. A caregiver witnesses him nosing his surroundings and even the floor but doesn’t think much of it. Later, when a caregiver comes by with zucchinis, she sees Chen rooting around in his feces. Yikes. He stops when she gives them their treats but starts right back up again once he is finished and even starts nosing Becca. Chen is highly motivated to root around in the dirt, but he can’t. In his frustration, Chen has redirected his desire to root around in the dirt to rooting around and manipulating his feces. Chen is motivated to carry out normal, healthy behavior in this case. Environmental factors thwart Chen’s attempt to carry out a highly motivated natural behavior, so in his frustration, he is carrying out a naturally motivated behavior on an inappropriate object.

Possible Solution(s)

The bare environment and resulting lack of stimulation have left Chen bored and frustrated. The staff didn’t realize he would get so bored so quickly, and they did some research on enrichment for Chen (and for other residents). They offer him straw, allowing him to root around and make nice bedding. This reduces the frequency of rooting at feces, but, now realizing the negative effect of the bare environment and lack of things to engage with and the ability to perform natural behaviors, they come up with an enrichment plan for Chen and Becca, with plans to assess the needs of other residents as well. In addition to providing straw, they start hiding treats around their living space in the straw, and someone brings in a log to hide treats under. They change this log out every so often with cardboard boxes that Chen enjoys tearing up. Staff watch carefully and remove the boxes once they are destroyed to ensure he doesn’t ingest them. They also read that calm instrumental music can positively affect Chen and lower stress levels, so they start providing this during the afternoon when a staff member can be present to observe his reaction and the reaction of others. This ensures it is actually helpful and not aversive to anyone. A strongly knotted rope with a large rubber ring on the end is attached to a sturdy post inside for Chen to manipulate. Becca also benefits from this, and staff ensures there are multiple enrichment items at any given time so everyone can participate.

Outcome

Success! Providing rotating enrichment on a schedule provided the necessary mental stimulation for Chen and Becca, eventually extinguishing the abnormal behavior.

Autonomy And Choice

A lack of control over one’s environment can be extremely distressing. In a human-managed environment, so many choices are made by caregivers. Many of these choices must necessarily be made by a caregiver, but there are opportunities where choices can be offered to residents. Let’s look at possible opportunities to provide residents with choice and control over their own lives:

- Choice of privacy over social spaces: This may look like hiding away from other residents, walking away when a human enters their living space, or hiding from view when tours approach. Wherever possible, residents should have autonomyThe ability for individuals to have access to free movement, appropriate food, and the ability to reasonably avoid situations they wish to avoid..

- Choice of physical touch: While there are times that a resident’s clear preference not to be touched must be overridden for their health and safety, efforts should be made to encourage touch through multiple positive and ongoing interactions to build trust, reduce fear, and stress, and increase the chances a resident will choose to seek out or accept physical touch. Learned helplessness may look like acceptance, but the resident has given up because they realize they have no control. Flooding should never be a part of a caregiver’s strategy to get residents to accept touch, and force should only be used when absolutely necessary, using the gentlest techniques possible. The more negative interactions, the less likely a resident will feel comfortable being touched.

- Choice of dietary factors: Residents often cannot choose what they eat, where they eat, when they eat, or how long they eat. Where applicable, provide residents with natural eating opportunities to graze and browse, allowing them to choose which resident-appropriate plants. Offer them choices between different produce and let them choose which they prefer.

- Choice to engage and manipulate the environment: Offering treat mechanisms where a resident receives a treat when manipulating the target object offers a sense of control. This might look like Roxy, a goat, receiving a bit of food when she pulls on a rope attached to a lever that releases a treat. Other things include noise makers where a resident can ring a bell or something that changes their environment. This might look like Quackers, a duckUnless explicitly mentioned, we are referring to domesticated duck breeds, not wild ducks, who may have unique needs not covered by this resource., playing with an interactive baby toy. It could also look like providing multiple nesting material options, letting residents choose what they want, and allowing them to change their environment to their liking.

- Choice of companions: Do your best to protect social bonds, allowing residents to choose who they spend their time with.

- Choice of where to rest: Offering multiple sleep areas, when possible, gives residents choice. Providing goats with platforms of varying heights or chickens with different roosting places gives them choice. Of course, there may be intergroup competition for certain resting areas, and care should be taken to prevent confrontations.

- Choice of whether to participate: Sometimes, for the sake of a resident’s health and safety, caregivers must ensure that residents receive their vaccinations, hoof trims, health checks, and other less-than-fun experiences. However, if a resident strongly indicates they do not want to participate, ask yourself: “Does this have to be done right now? Does this have to be done today? Will this individual’s health suffer if we spend a week utilizing positive learning opportunities that may make future attempts easier? Is there another way to go about this? Is this the best approach? Are there elements in the environment that may be contributing to their choice not to participate? Is this making matters worse? Is this endangering the resident, staff, or other residents?

Example: Alphie

Background

Alphie is a llama resident who lives with his mother and sister. Their outdoor living space has plenty of green grass, two dust bathing areas, a little mound, and even a kiddie pool (in which Alphie loves to lie down in hotter weather). The sanctuary just started offering tours. During tours, Alphie, Mollie, and Kimba (Alphie’s mother and sister) are kept in a smaller paddock so visitors can interact with them.

Abnormal Behavior

The guide notices Alphie standing as far away as possible, pacing back and forth. He continues to do this while visitors are present. Later the guide mentions this to a caretaker. The caretaker checks on Alphie, but he seems fine. A few days later, the same thing happens during a tour. He even kept pacing after they walked away.

Possible Solution

The next time a tour came through, a caregiver gave the llama residents the option to go out in the pasture away from the visitors. Mollie and Kimba were curious and seemed torn between staying and following Alphie, who went into the pasture as soon as he was given the opportunity. While Alphie paced less, it was clear he was still uncomfortable. Staff decided to construct a visual barrier by stretching shade cloth between two tall posts while a structure was being built. Having the option of whether to interact with visitors and whether to remain out of sight or not made a big difference in Alphie’s behavior.

Outcome

Success! Now when tours came by, Alphie would simply walk into the pasture and graze, sometimes hiding from view but sometimes watching, as simply having control over this aspect of his life lowered his stress levels. It is essential that residents have the option to remove themselves from tour areas and not be pressured to interact.

Unfortunately, some factors are simply out of our control. However, learning all we can about a resident’s personal history, genetics/breed, and personality can help us provide the best care. Let us discuss how gathering this information can help you as a caregiver:

Personal History

Gathering a resident’s history as possible will help you better understand their experience and how to approach their care.

- What conditions were they kept in?

- Who were/are their companions?

- Did they have human interaction?

- If yes, do we know if it was positive or negative?

- What was their diet?

- How did they respond to staff during the rescue?

- Did they approach or allow an approach?

- Did they run, charge, or give body language that indicated they were upset?

- Are they familiar with handling techniques?

- Are there signs of neglect?

- Overgrown hooves or nails?

- Signs of malnutrition or starvation?

- Overgrown wool, coats, or hair in poor condition?

- Were they ill or injured?

- How did they respond during loading and transport?

The answers to these questions can help you a great deal. They might be unaccustomed or fearful of hoof trims if they had overgrown hooves. If they ran from the sight of staff, they might fear a direct approach, and positively reinforced learning sessions could build trust and prevent stress. If they were alone, they might be uncertain about entering a social group. In terms of abnormal behaviors, it can help you make sense of their behavior and how to best address it. Let’s look at an example:

Example: Norman

Norman is a healthy, weaned calf that was recently rescued. Previously, he lived with his mother and a small herd. Sadly, he lost his mother, and the farmer was persuaded to give him to a local animal sanctuary. When he arrives, he receives an exam, and the vet determines he is physically healthy, to the relief of his caregivers. Of course, he is kept in quarantineThe policy or space in which an individual is separately housed away from others as a preventative measure to protect other residents from potentially contagious health conditions, such as in the case of new residents or residents who may have been exposed to certain diseases. to be safe, as some illnesses can show up later. The quarantine area is on the other side of the sanctuary, away from the cow living space. From where he is, he cannot see the other cowWhile "cow" can be defined to refer exclusively to female cattle, at The Open Sanctuary Project we refer to domesticated cattle of all ages and sexes as "cows." residents. He is kept indoors in a smaller living space and receives a bottle. The week he is supposed to join Bell and her older calf Trudie, a storm damages some of the fencings. This extends the time that Norman is isolated from other cow residents. During this time, caregivers notice that he starts exhibiting tongue-rolling behavior. Tongue-rolling behavior is when a cow flicks their tongue out or around and repeatedly rolls it back inside their mouth. This is repetitive, so not just a normal lick of the nose. This abnormal behavior is sadly seen in calves exploited for veal. The stress of separation, isolationIn medical and health-related circumstances, isolation represents the act or policy of separating an individual with a contagious health condition from other residents in order to prevent the spread of disease. In non-medical circumstances, isolation represents the act of preventing an individual from being near their companions due to forced separation. Forcibly isolating an individual to live alone and apart from their companions can result in boredom, loneliness, anxiety, and distress., improper diet, and an inability to exhibit other normal behaviors can be all factors in developing this maladaptive behavior.

Knowing Norman’s history allows his caretakers to understand better why they see these abnormal behaviors and presents possible solutions. Integrating Norman safely into a social setting and transitioning him onto calf starter and hay could go a long way in reducing or even entirely extinguishing the abnormal behaviors.

Personality/Temperament

There has been research into how personality factors into the development of abnormal behaviors. This topic is more than can be effectively covered here and requires a resource (or multiple resources) of its own. That being said, it is clear that getting to know individual residents allows you to provide better care. Everyone has their own personality, which will come into play in how they respond to certain environmental factors. As you get to know a resident, here are some questions you can ask yourself:

- Do they readily approach caregivers and volunteers?

- Do they spend more time alone or with others?

- Are they the last to get treats or food?

- Are they easily surprised?

- Do they shy away, stand their ground, or approach novel items in their living space?

- Do they often use visual barriers in their living spaces?

- Do they confront other members of their group?

- Do they stand their ground or remove themselves if confronted by another group member?

- Do they explore their surroundings a lot?

- Do you see them in open spaces frequently?

Questions like these can help you determine how bold, confident, and secure they feel and where they are in the social hierarchy as it exists in their species. Understanding an individual is helpful when providing care and developing a relationship with them. In another resource, we will explore how personality traits may predispose individuals of different species to develop abnormal behaviors.

Careful With Labels

While understanding a resident’s temperament is important, care must be taken to refrain from placing potentially harmful labels on residents, as it may affect the quality of care they receive. For example, if someone says one day, “Ginger is mean!” when they come in from feeding pig residents, the person who hears that may change the way they approach Ginger, shifting their body language, how and where they feed her, and avoid interacting with her. Volunteers may be told not to go in with her. In reality, Ginger grabbed the food bucket from the caretaker’s hand and scared them. This doesn’t mean Ginger is mean or that all interaction should be avoided. Care should be taken when feeding Ginger; a care plan can be implemented without changing how staff and volunteers see WHO she is. Describe interactions rather than putting a simple label on a resident. You can learn more about how to describe resident behavior here.

Genetics

Genetics is another area you don’t have any control over and is also a topic too complex to cover in this resource. However, building a greater understanding of how genetics can play a part in developing abnormal behaviors can help caregivers be on the lookout. Several studies focusing on different farmed animalA species or specific breed of animal that is raised by humans for the use of their bodies or what comes from their bodies. species show certain breeds have a predisposition for developing abnormal behaviors, such as feather pecking in chickens, tail-biting in pigs, and box-weaving in horses. Sadly, sometimes the traits animals are exploited for, such as increased growth rate, milk production, or speed (horses), also go along with behavioral traits predisposing individuals to abnormal behaviors. There are even studies on the correlation between whorl patterns in a horse’s hair and their level of reactivity!

Caring for residents is a lot of work. Knowing what you can do to prevent psychological distress and the development of abnormal behaviors is a valuable tool in a caregiver’s resource toolbox. We hope this resource has been helpful and provides a deeper understanding of what factors can significantly impact resident well-being and behaviors and actionable steps to prevent and address any abnormal behaviors. Stay tuned for further resources on the topic!

SOURCES:

Chapter 8: Animal Well-Being And Behavioral Needs On The Farm | Improving Animal WelfarePractices and policies that promote the well-being of nonhuman animals, specifically their health and comfort.: A Practical Approach (Non-Compassionate Source)

Behavioral Problems Of Cattle | The Merck Veterinary Manual (Non-Compassionate Source)

Play Behavior And Environmental Enrichment In Pigs | Wageningen University & Research (Non-Compassionate Source)

Behavioral And Health Problems Of Poultry Related To Rearing Systems | Ankara Univ Vet Fak Derg (Non-Compassionate Source)

Factors Associated With The Development And Prevalence Of Abnormal Behaviors In Horses: Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis | Journal Of Equine Veterinary Science (Non-Compassionate Source)

Effects Of Dietary Fibre And Feeding Frequency On Wool Biting And Aggressive Behaviours In Housed Merino Sheep | Australian Journal Of Experimental Agriculture (Non-Compassionate Source)

Omnivores Going Astray: A Review And New Synthesis Of Abnormal Behavior In Pigs And Laying Hens | Frontiers In Veterinary Science (Non-Compassionate Source)

Chapter 1 – Behavioral Genetics And Animal Science | Genetics And The Behavior Of Domestic Animals (Third Edition) (Non-Compassionate Source)

Age-Related Changes In Fear, Sociality And Pecking Behaviours In Two Strains Of Laying Hen | British Poultry Science (Non-Compassionate Source)

Interplay Between Environmental And Genetic Factors In The Behavior Of Horses | Horse Behavior And Welfare (Non-Compassionate Source)

Non-Compassionate Source?

If a source includes the (Non-Compassionate Source) tag, it means that we do not endorse that particular source’s views about animals, even if some of their insights are valuable from a care perspective. See a more detailed explanation here.