Veterinary Review Initiative

This resource has been reviewed for accuracy and clarity by a qualified Doctor of Veterinary Medicine with farmed animal sanctuaryAn animal sanctuary that primarily cares for rescued animals that were farmed by humans. experience as of December 2023. Check out more information on our Veterinary Review Initiative here!

If you provide care for equines, you likely already know that laminitis is a significant concern when considering the health of equine residents. Learning about laminitis is absolutely necessary if you are considering rescuing or providing sanctuary to equines. You will need to know how to identify signs of laminitis and provide proper care in order to prevent it. Laminitis is a serious condition that can lead to the death of affected equines worldwide. Because donkeys, and to a lesser extent, mules, have care needs that differ from horses, we will provide two laminitis resources. This resource will cover the general signs, stages, and causes of laminitis in horses, as well as how veterinarians make a diagnosis and treatment/prevention. Our other resource will cover the same topics while focusing on the unique care needs of donkey and mule residents. Let’s get started!

What Is Laminitis?

Laminitis Requires URGENT Medical Care

If you suspect a resident has laminitis or there has been an event that could result in a resident developing laminitis, call your veterinarian as soon as possible so the veterinarian can examine and diagnose the issue. The faster treatment can be administered, the better the prognosis. Failing to act quickly can result in irreparable damage and even the necessity of euthanasia in some cases. When in doubt, call your veterinarian. We also recommend that prior to laminitis developing, you understand from your veterinarian what they think are symptoms that warrant an urgent call, which may include understanding the chronicity and severity of the symptoms.

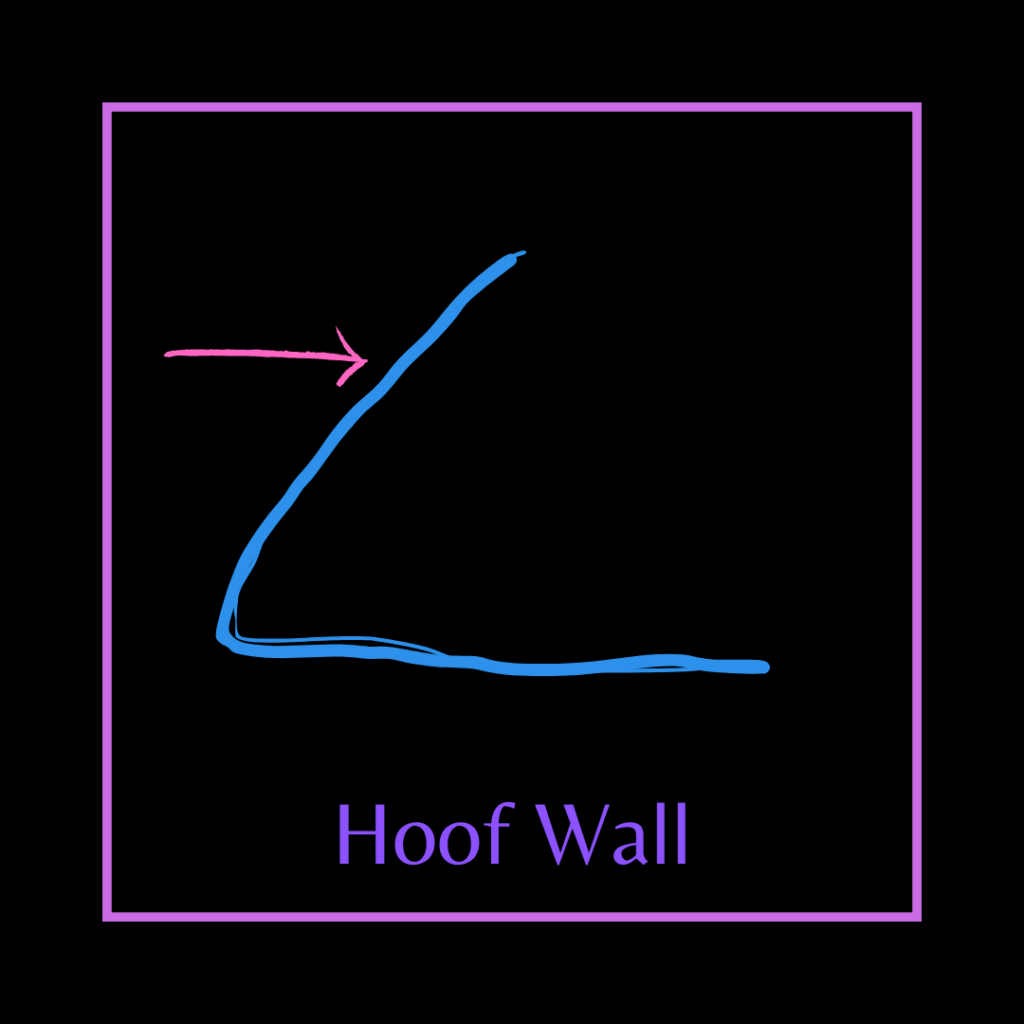

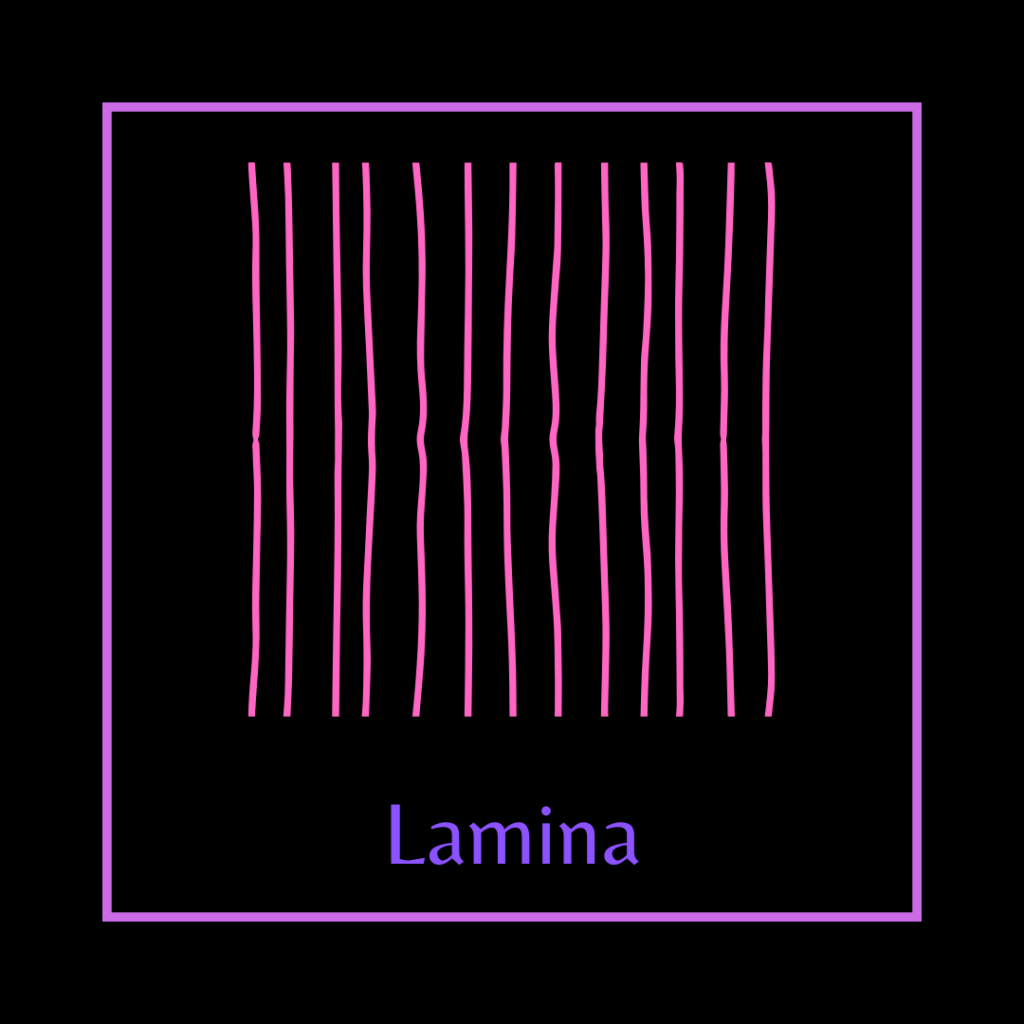

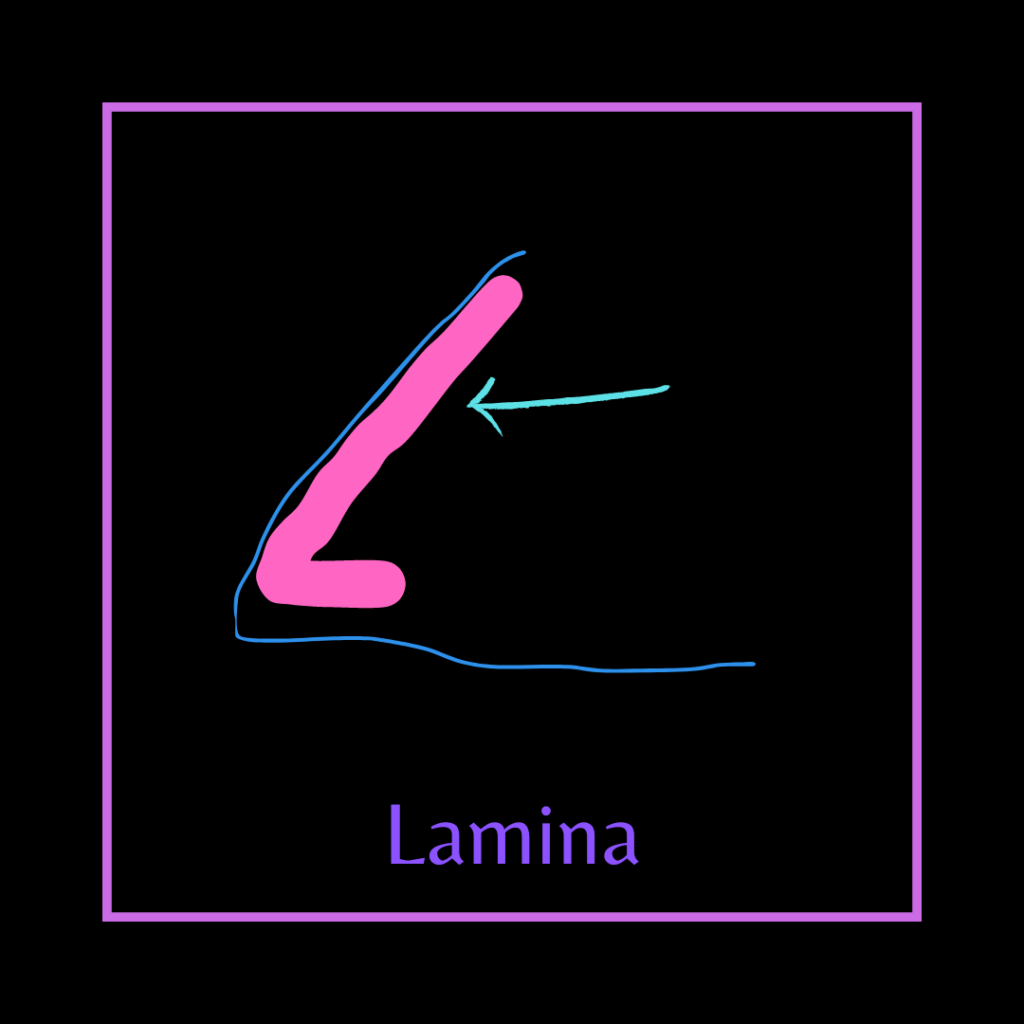

In the simplest terms, laminitis can be defined as inflammation of the lamina of the hoof. The lamina is a strong tissue that connects the hoof wall to the coffin bone, an integral part of a healthy hoof.

According to the American Association of Equine Practitioners, laminitis is defined as:

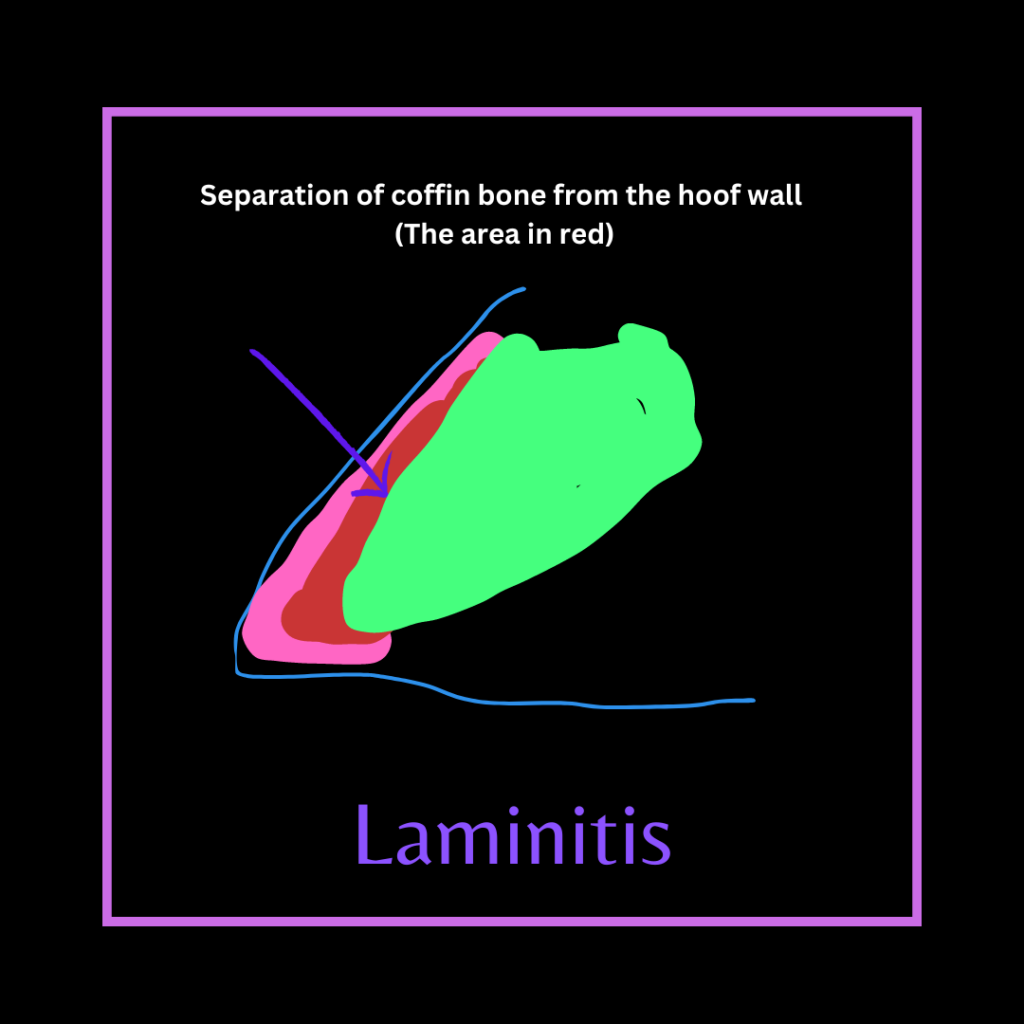

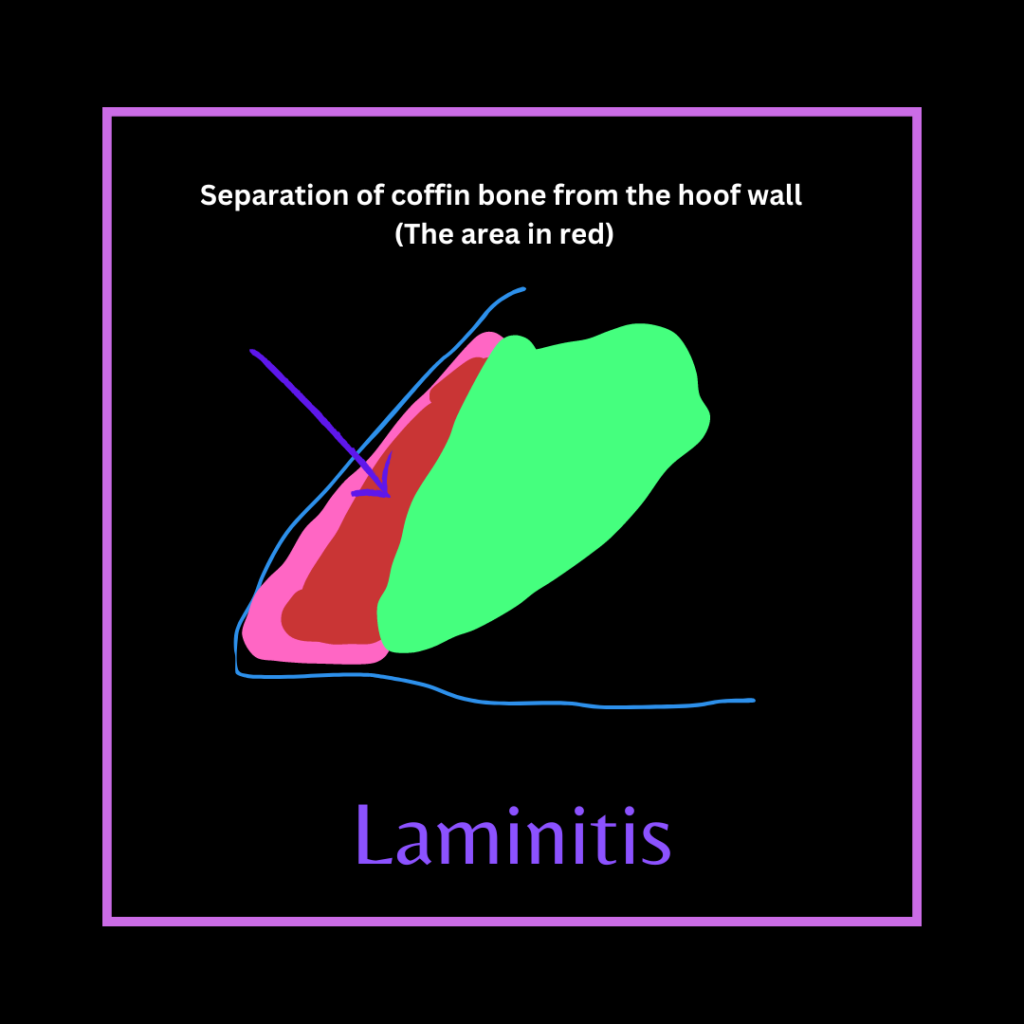

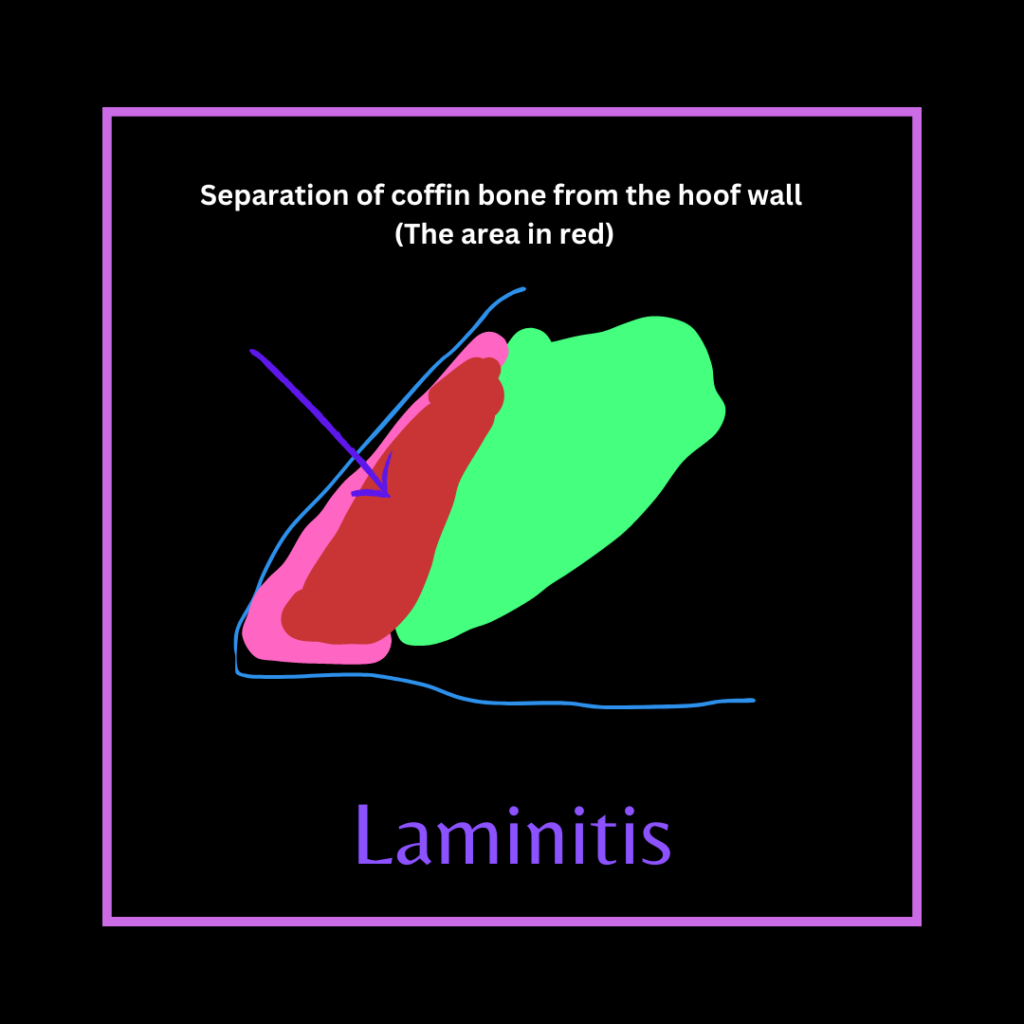

“Laminitis results from the disruption (constant, intermittent, or short-term) of blood flow to the sensitive and insensitive laminae. These laminae structures within the foot secure the coffin bone (the wedge-shaped bone within the foot) to the hoof wall. Inflammation often permanently weakens the laminae and interferes with the wall/bone bond. In severe cases, the bone and the hoof wall can separate. In these situations, the coffin bone may rotate within the foot, be displaced downward (“sink”), and eventually penetrate the sole.”

As you may imagine, this can be a terribly painful condition. Laminitis can range in severity, and a mild case may not cause much discomfort. However, everybody is different, and how we experience pain can also differ. If the condition worsens, discomfort, pain, and permanent damage can result. Sources state that between 4-7 percent of equines around the world are euthanized due to laminitis each year. The percentage in different parts of the world varies significantly, however. In the United States, for example, this number is lower. Usually, laminitis is found in the front two hooves, which bear the most weight but can also affect the back hooves. While laminitis can affect a single hoof or all hooves, it often affects two, with the front hooves being more commonly affected as they bear more weight.

Founder Versus Laminitis

There is a good chance you have heard these two terms interchangeably. However, an equine resident can have laminitis and not be “foundering.” Technically, laminitis is the condition that can lead to founder. Founder, in the technical sense, would refer to a severe long-term case where the coffin bone has separated from the hoof wall and rotated. Basically, founder technically refers to the result of severe laminitis.

However, some conditions use the term founder to refer to laminitis, such as grass founder. This does not necessarily mean it is a permanently severe case where the coffin bone has rotated. It is okay to use both terms as long as both parties know what they refer to.

Stages Of Laminitis

There are four stages of laminitis. Each stage can be identified by its characteristics, which we will review in more detail below. Let’s start with Stage One.

Stage One: Developmental Laminitis

Developmental Laminitis is the stage where there are no symptoms or signs present, but something has happened to cause laminitis to start developing. You may not know if a horse is in a developmental stage. If you did not witness an event or don’t have a present lab workup, you will not know until signs begin to become apparent.

For example, you found Sadie at the storage shed where the food is kept. Somehow, she broke through part of the fencing and now has her head in a barrel of sweet feed. You don’t know how long she has been there or how much she has eaten. After moving her into a stall, you call the caregiver who generally cares for equine residents, and together you confer and discover that she ate quite a large amount of grain. This can cause laminitis. Your fellow caregiverSomeone who provides daily care, specifically for animal residents at an animal sanctuary, shelter, or rescue. calls your veterinarian immediately while you stay with Sadie. The veterinarian arrives quickly to treat and hopefully prevent an acute stage of laminitis. She rests easily in her indoor living area and isn’t showing signs of laminitis. Sadie is in the developmental stage of laminitis. It is essential to be aware that this could also cause colic, a potentially life-threatening condition, and the vet will check her for signs.

Stage Two: Acute Laminitis

The acute stage begins when signs become apparent and generally lasts 24 to 72 hours. Symptoms can come on suddenly and severely during this time. Common signs of Acute Laminitis include:

- Lameness (Shifting while standing, turning circles, reluctant to put weight on hoof/hooves)

- Heat in the affected hooves

- An increased digital pulse

- A “sawhorse stance” where the affected individual appears to push back with their front hooves so more weight is on their back hooves.

- Reluctant to walk or stand or hesitantly placing their hooves down

- Resistance to picking up a hoof as it will place more pressure on other affected hooves.

- Reaction to hoof tester (no reaction doesn’t necessarily mean no pain or laminitis, but a “positive” reaction such as pulling away when the tester is used correctly can help pinpoint pain in a hoof.)

Stage Three: Subacute Laminitis

Subacute Laminitis occurs when symptoms remain but may lessen, but there has been no displacement of the coffin bone, which happens in Chronic Laminitis. Some symptoms may stop altogether. During this time, the body is healing while receiving treatment, and the episode will hopefully not result in the hoof wall and coffin bone becoming detached from each other and the coffin bone shifting. While the body may heal, future episodes generally occur once an equine has laminitis. This may remain in the acute or subacute stages or become chronic.

Stage 4: Chronic Laminitis

Chronic Laminitis occurs when symptoms continue over a week, and the coffin bone becomes displaced. The whole shape of the hoof’s anatomy can change, and, in severe cases, the coffin bone may push through the sole of the hoof. The hoof wall may completely slough off. An equine resident with Chronic Laminitis will have recurrent episodes, the severity of which can vary. This depends on the success of treatments and whether the hoof capsule is stable. Common signs of Chronic Laminitis include:

- Rotation and displacement of coffin bone

- Separation of the coronary band

- Bruised soles

- Abscesses

- A broad white line (Seedy Toe)

- Dropped soles

- Dished hooves

- Rings in the hoof wall are narrower at the toe and broader at the heel

- Shifting

- Frequent recumbencyRecumbency is the state of leaning, resting, or reclining.

- Cresty (thick) neck

- Lameness

Now that we have covered the stages and signs of laminitis in horses let’s move on to predisposing factors and causes. Prevention is undoubtedly best, and understanding what factors may predispose a resident or cause a resident to develop laminitis can help you be on the lookout for possible risks.

Risk Factors And Causes

While all equines are potentially at risk of developing laminitis under certain circumstances, some individuals may be predisposed (at a higher risk). As you will learn later, this may be different for donkeys than horses. For now, we will use the largest source of knowledge about laminitis in equines in general, primarily taken from data on horses.

Predisposing Factors

- Certain endocrine disorders, such as Cushing’s Disease

- Heavy breeds (draft), ponies, and miniature horses are at increased risk.

- Recent significant weight gain

- Significantly excessive weight

- Access to lush pastures

- A diet high in concentrates

- Systemic Infections

- Mares that have given birth recently, especially those with a retained placenta

- Previous history of laminitis

- Soreness/lameness post trimming or shoeing

- Leg or hoof injury that causes the individual to put more weight on other hooves

Now that we have identified possible predisposing factors, we can look at causes. The difference between predisposing factors and causes is that predisposing factors increase the likelihood of an individual developing laminitis but are not necessarily the cause. Some risk factors may eventually be a causal factor but often are just correlational in nature.

Apply This List To Current Equine Residents

After reading that list of predisposing factors, does anyone come to mind among your residents? Once an individual develops a case of laminitis, they will also be prone to future episodes. Meet with your care team and discuss individuals who may be predisposed to developing laminitis. Develop your observational skills. Now is the best time to talk to your veterinarian (if you haven’t already) about an individual’s risk of laminitis, what to look out for, and a care plan most likely to prevent laminitis.

Causes

- Grain overload

- Black Walnut shavings used as bedding

- Excessive hoof trimming

- Improper hoof trimming or shoeing

- Heavy weight-bearing/trauma to the hoof

- Systemic infections/inflammation (endotoxemia)

- Excessive intake of lush grass

- Endocrine disorders

Some of the predisposing factors may, in fact, become a cause. However, this is not always the case. Now that we have covered predisposing factors and causes let’s proceed to diagnosis.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is generally relatively simple. A veterinarian will note apparent clinical signs, examine their history, and perform a physical exam. They may take x-rays or do a venogram, as well to ascertain the position of the coffin bone and damage or do blood tests to test for metabolic disorders or inflammatory or infectious markers.

Obvious clinical signs include the strange saw-horse stance, reluctance to stand or walk, gaitA specific way of moving and the rhythmic patterns of hooves and legs. Gaits are natural (walking, trotting, galloping) or acquired meaning humans have had a hand in changing their gaits for "sport"., and signs of pain that can be read in body language and facial expression. They will take a history, asking whether they have had access to lush pasture, had issues like this before, had their hooves recently trimmed, the amount of grain they are fed, whether they have any known metabolic disease, etc. They will do their own exam, during which times they will take the temperature of each hoof either by touch or a special thermometer, check their digital pulse, exam the hoof (and foreleg) for any injury or sign of disease, and use a hoof tester to determine whether the individual is sensitive in any areas of their hoof.

Treatment

Treatment options for laminitis will vary depending on the cause, the severity, and other health issues they may have. However, veterinarians generally recommend stall rest and extra cushy bedding. They will recommend a pain management plan that includes pain medications and possibly icing the hooves or wearing special boots to lessen discomfort. Often, they will prescribe and administer something like acepromazine, which increases blood flow to the hooves. It also acts as a sedative, encouraging the individual to lie down and rest.

If an underlying health issue causes the laminitis, they will treat that specifically. This could be Cushing disease, pneumonia, endotoxemia, or another health issue like an abscess. They may want to discuss unique trimming plans with your farrierSomeone who provides hoof trimming and care, especially for horses or cows in order to treat the issue. They may also recommend a temporary or permanent dietary change. While the cause of laminitis will determine the exact care plan, there are things you can plan on as a caregiver. Let’s list out steps your care team can take in the event of a resident developing laminitis.

- Prepare a small living area that is sheltered and limits movement. Ensure there is a thick layer of wood shavings (not black walnut shavings!!) or straw. You want them to have as little stress as possible on their hooves and want to lay down and rest.

- Remove any grains or treats until the veterinarian says otherwise. Ask them what diet they now recommend.

- Provide them fresh water (not ice-cold) and soaked (and rinsed) hay.

- Write a list of possible enrichment items and activities that encourage calm behavior and rest and those that provide novelty and stimulate the senses.

- Move a close companion nearby. It would be ideal if they shared a fence and could touch, see, and smell each other. This can help them remain calm.

- Check their digital pulse and hoof temp daily.

- Ask your vet what supplies they would like you to have on hand in case someone develops laminitis.

Caregiver Protocol

If you suspect a resident has laminitis, it is vital you contact your veterinarian immediately. Laminitis is an EMERGENCY. Even though a vet will perform a physical exam when they arrive, it is helpful to do a health check and write down anything unusual you note about their movement, behavior, and relevant present and past health issues. You should check their hoof temp and digital pulse rate and look at their hoof for any apparent injury. This will allow you to give your veterinarian pertinent information immediately. Be sure to alert the whole care team to the situation and the new care guidelines so someone doesn’t inadvertently cause a resident’s symptoms to worsen.

Based on the severity of symptoms, your veterinarian may recommend stall rest and have you walk them slowly to their indoor area with a thick bedding layer. If the horse is recumbent, refuses to rise, or is resistant to taking any steps, don’t move them as it may cause irreparable damage to their hooves. Remove grain and access to lush green pastures, separate them from rambunctious residents who may try to play with them or push them around, and be sure they have plenty of water and access to poorer quality hay or soaked hay that has been drained to remove sugars and carbohydrates. Always ask your vet what they want you to do. The above may not be appropriate in all cases.

Assessing Hoof Temperature And Digital Pulse

If you don’t know how to assess hoof temperature and digital pulse, now is the best time to learn! Luckily, it is a relatively simple process. This link provides written, video, and audio instructions on how to check hoof temperature and digital pulse. This can all be done by hand, but for a more accurate reading of temperature, there are special hoof thermometers that you can purchase. These allow you to get a precise temperature to compare with other hooves and also give you a baseline temp for when no issues are present. Be sure to record your findings so other caregivers and your veterinarian will have an accurate history.

Prevention

Of course, prevention, while not always possible, is best. Laminitis can be debilitating, and no one wants their residents to develop it.

- Avoid giving residents excessive carbohydrates.

- Watch for changes in behavior.

- Use care when allowing residents access to lush green pastures.

- Ensure all residents receive regular hoof trims.

- Keep an eye out for signs of metabolic diseases.

- Clean and check hooves daily.

- Ensure their intake exam includes blood tests that can identify signs of infection, inflammation, and abnormal hormone levels.

- Act quickly when something seems off. Catching issues early on can significantly affect how and if a resident heals.

- Discuss laminitis issues with your veterinarian before it’s a problem.

- Keep food storage areas secure.

We recommend you discuss your resident’s risk of laminitis with your veterinarian. We hope the resource has helped give you a good foundation to start that conversation! Remember, laminitis is an emergency and should involve a call to your veterinarian ASAP. If you have a resident on stall rest, check out our horse enrichment resource for ideas on providing them with fun and exciting experiences.

SOURCES

Everything You Need To Know About Laminitis | Irongate Equine Clinic

Laminitis In Horses | Blue Cross

What Is Laminitis, And How Can It Be Prevented Or Treated? | RSPCA

Laminitis | Royal Veterinary College (Non-Compassionate Source)

Laminitis: Prevention & Treatment | American Association Of Equine Practitioners (Non-Compassionate Source)

Laminitis | Southshore Equine Clinic And Diagnostic Center

Assess Heat & Digital Pulse In Feet | Horse Side Vet Guide

Risk Factors For Equine Laminitis: A Case-Control Study Conducted In Veterinary-Registered Horses And Ponies In Great Britain Between 2009 And 2011 | Veterinary Journal (Non-Compassionate Source)

Non-Compassionate Source?

If a source includes the (Non-Compassionate Source) tag, it means that we do not endorse that particular source’s views about animals, even if some of their insights are valuable from a care perspective. See a more detailed explanation here.